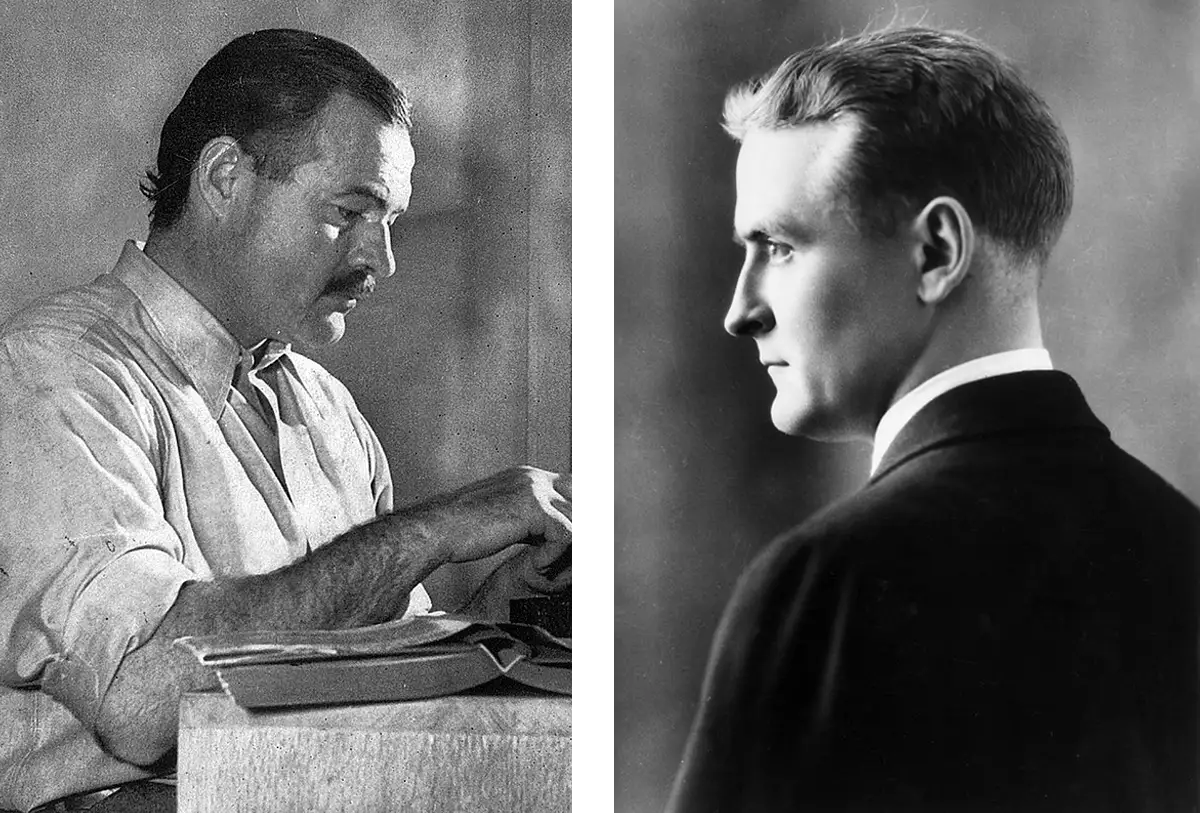

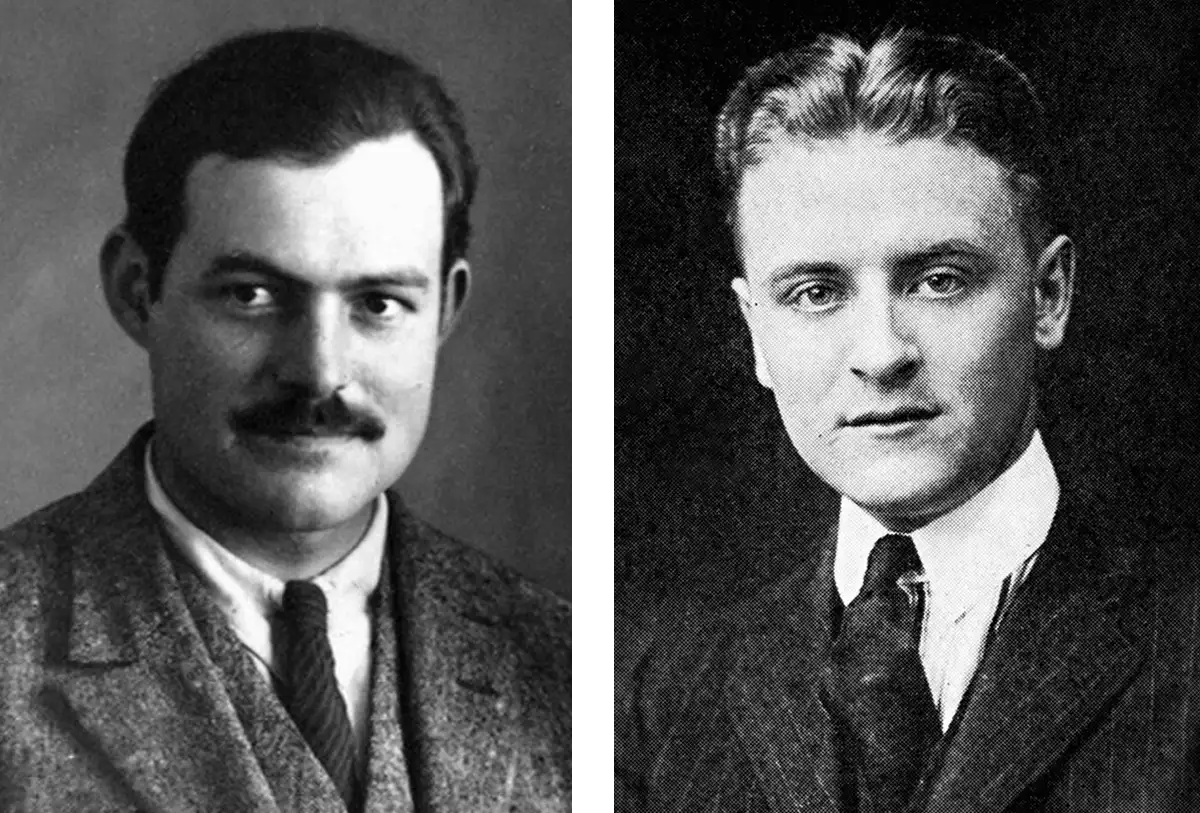

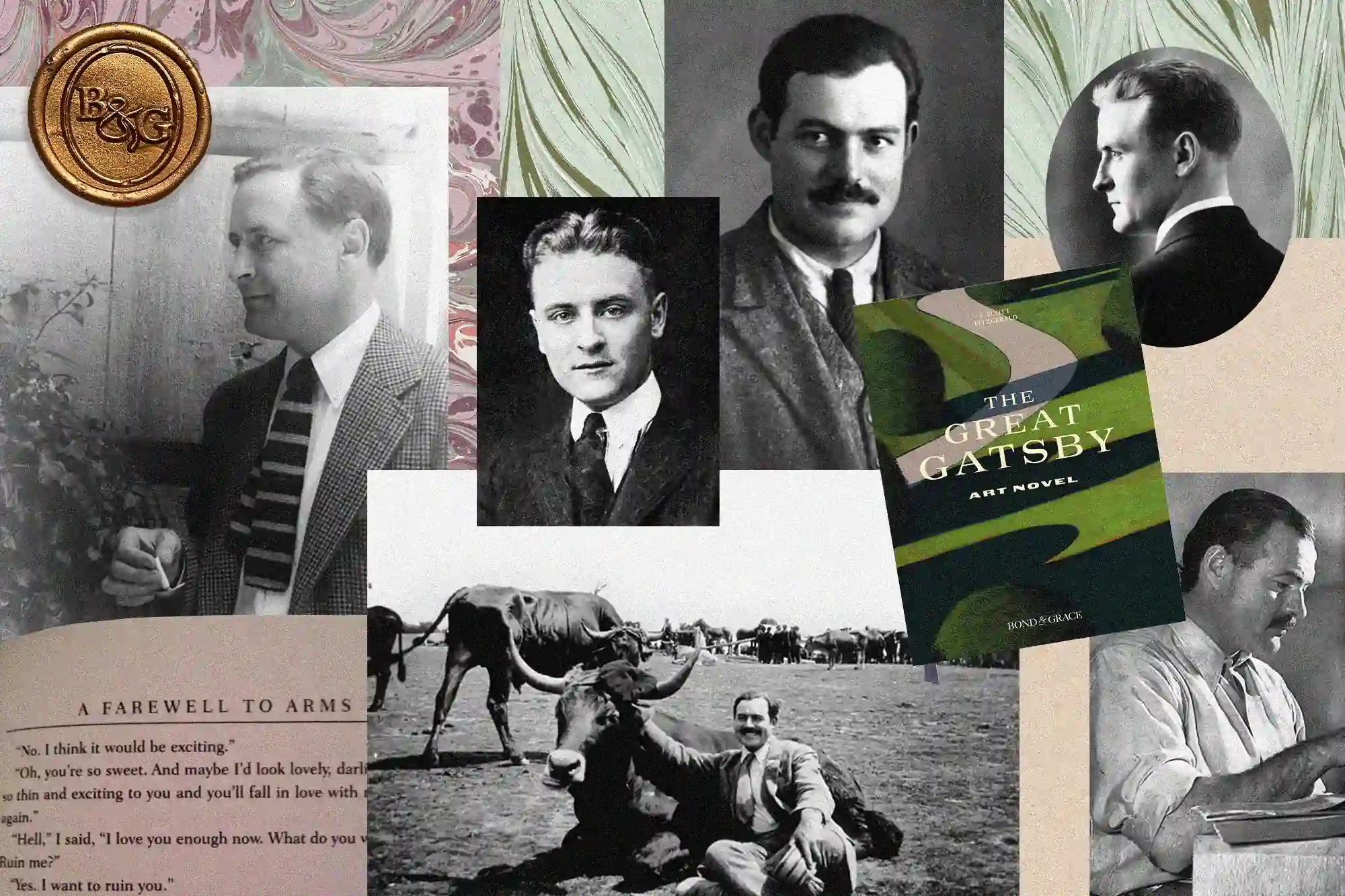

Few writers have left as great a mark on the world of American letters as Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald. These authors of novels such as The Sun Also Rises to The Great Gatsby were two of the greatest writers to emerge in the 1920s, documenting the human condition in all its post-war complexity. The pair had plenty in common; they were both part of “The Lost Generation” of American ex-pats living in Paris in the mid-1920s, they both worshipped at the altar of literary legend Gertrude Stein, they were both famous drinkers, and they were both wildly talented. Yet despite these similarities, they had an often fraught and turbulent relationship that has made them some of America’s most famous Frenemies.

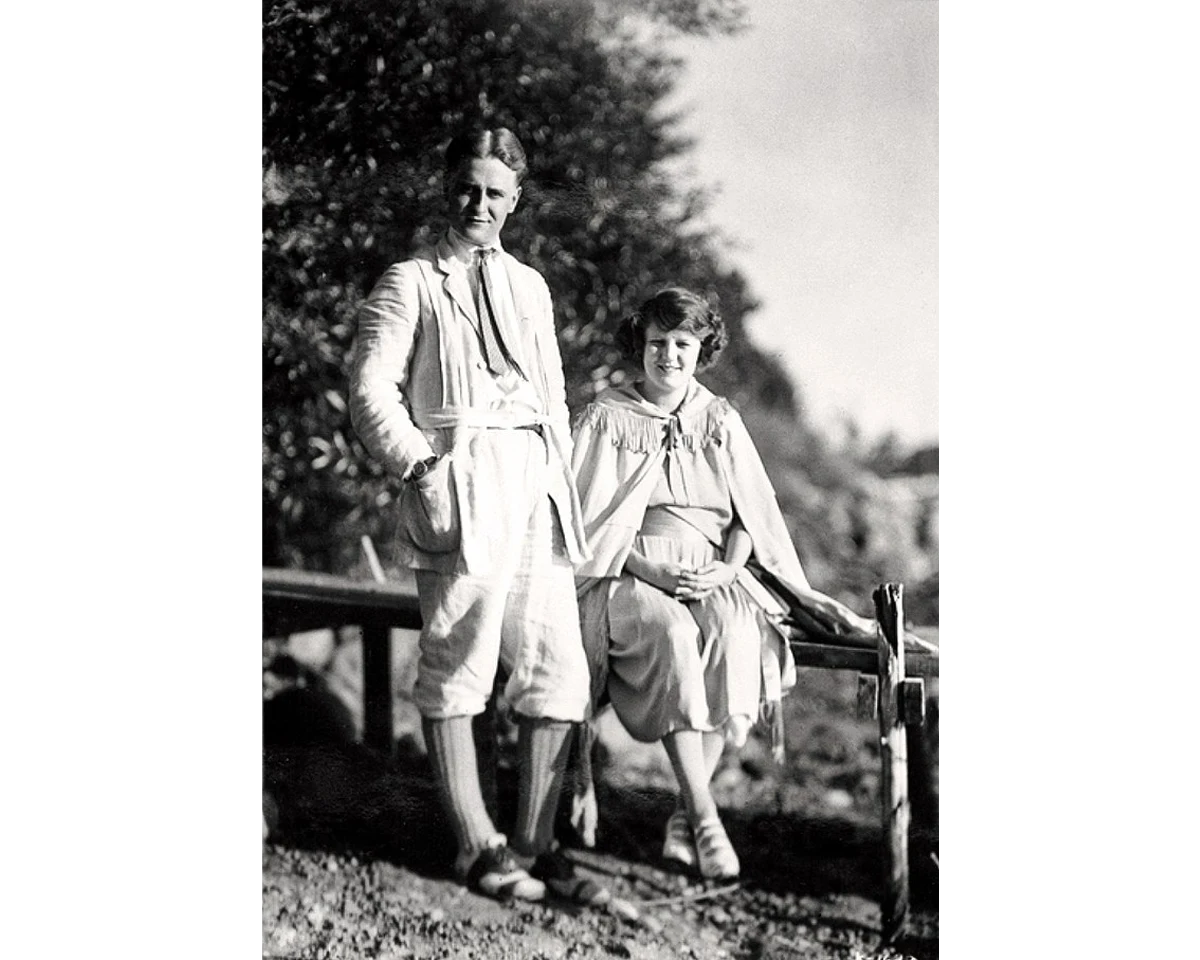

Scott and Ernest met for the first time in April 1925. Fitzgerald, three years and three novels older, was the more famous of the two. Hemingway, while having worked as a foreign correspondent, was only beginning his career as a novelist and looked up to Fitzgerald. Six months prior, Fitzgerald’s friend, writer and editor Edmund Wilson had reviewed a then-unpublished pamphlet of stories Hemingway had written called In Our Time. When Scott and Zelda arrived in Paris in April, Wilson suggested the two writers meet.

Over drinks at The Dingo Bar on Rue Delambre in Paris, Hemingway and Fitzgerald began a relationship that would span their lives and impact both their works. Despite Fitzgerald being the older, wealthier, and more acclaimed of the two, he immediately admired and idolized Hemingway.

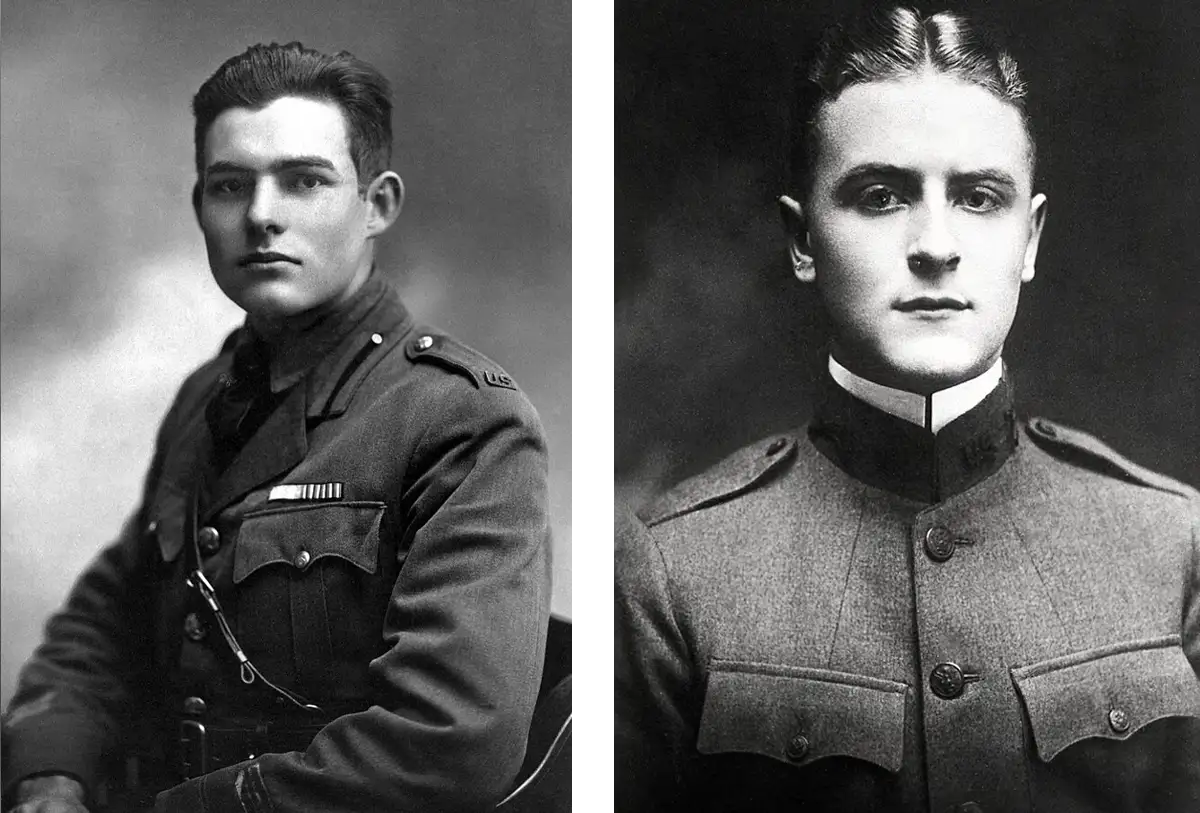

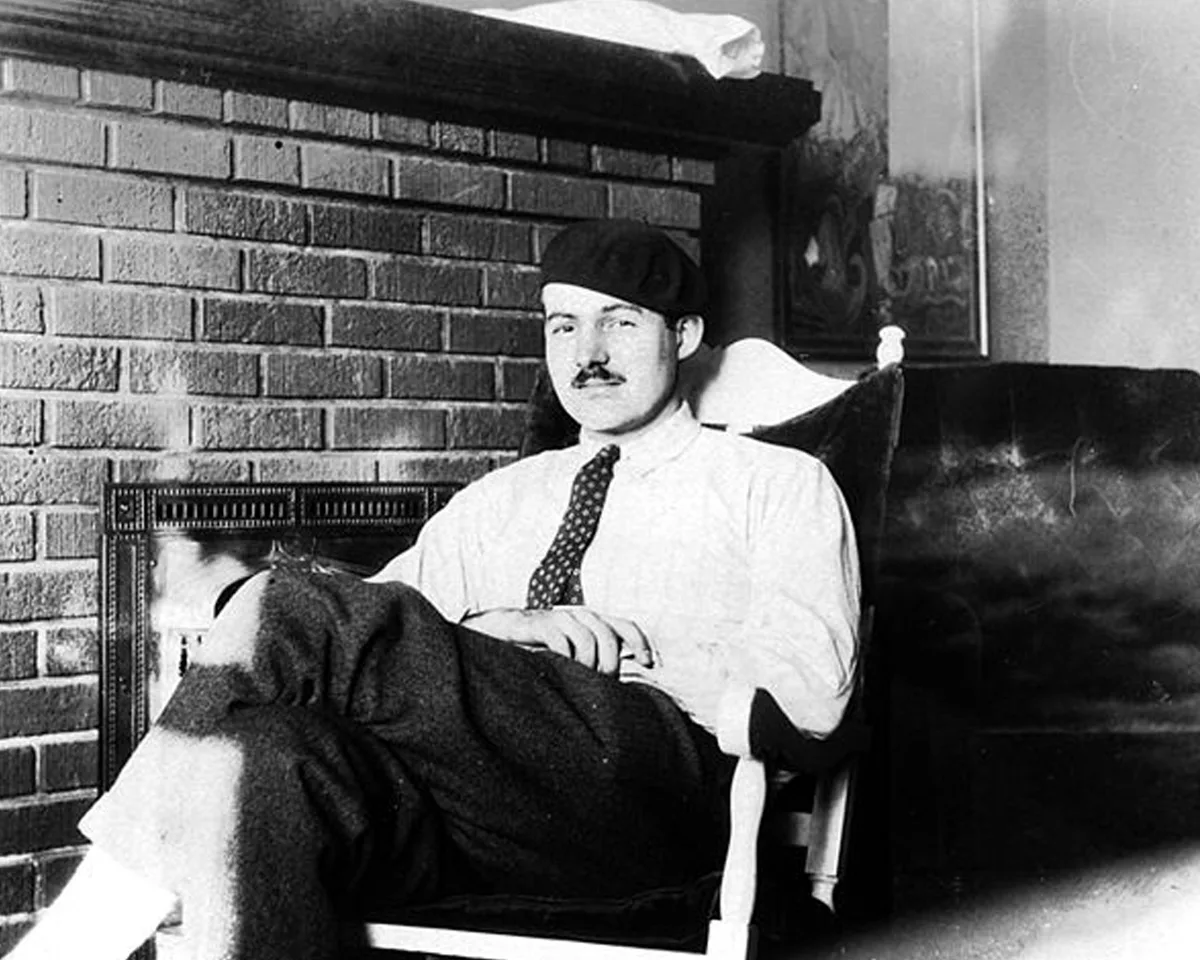

Fitzgerald had always looked up to hyper-masculine men. In college, he wanted to play football, but at 5'7" was too short and slim to make the team. Hemingway was six inches taller and forty pounds heavier. He’d also served in World War I and was wounded while serving with the Red Cross in Italy. Fitzgerald had wanted to be a soldier, but was stationed in Alabama and never made it overseas. A point of both insecurity and fascination for Fitzgerald, he went as far as collecting photos of soldiers who received gruesome injuries in wartime. He wrote to Hemingway in 1927 saying, “I have a new German war book Die Krieg Against Krieg, which shows men who mislaid their faces in Picardy and the Caucasus—you can imagine how I thumb it over, my mouth fairly slathering with fascination.”

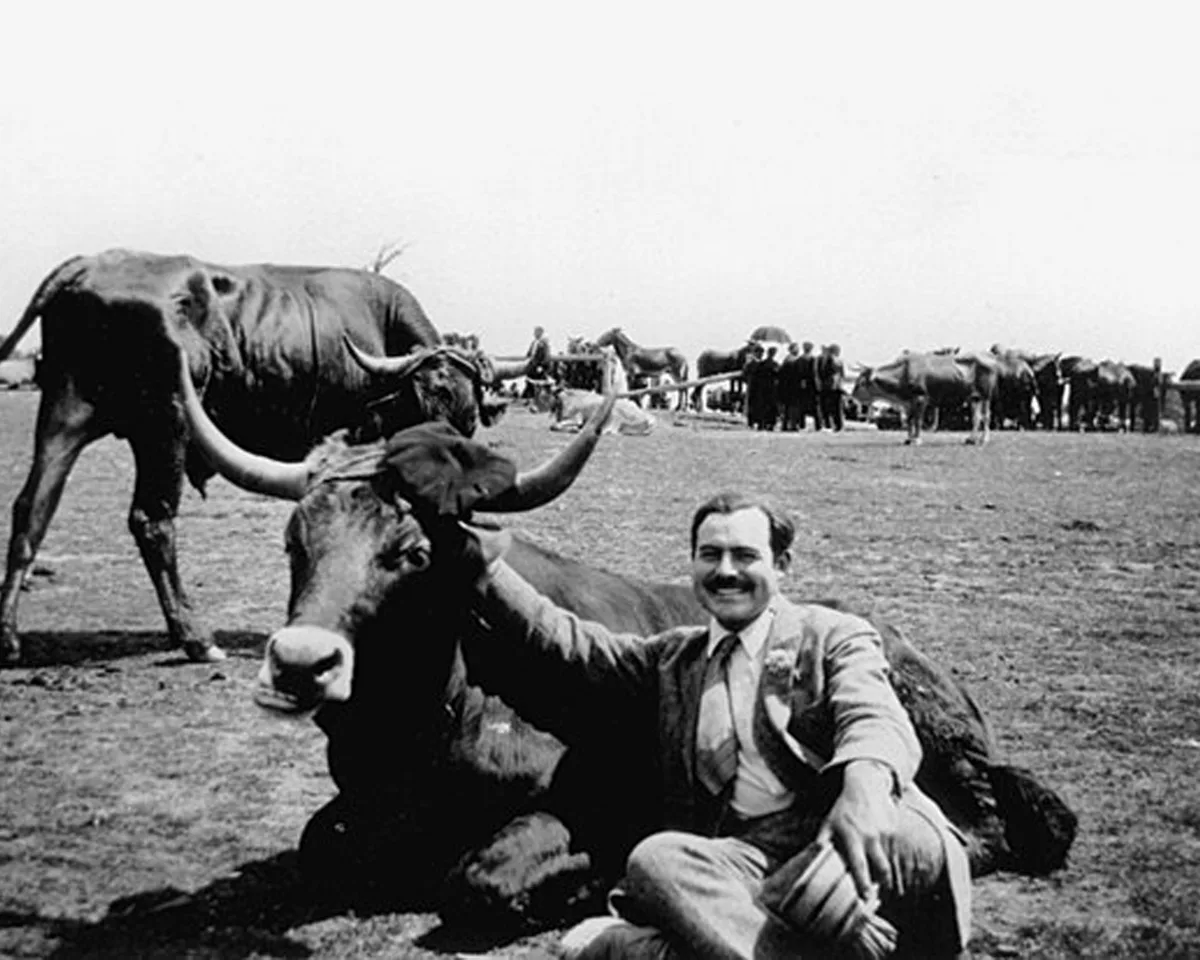

Fitzgerald’s admiration for Hemingway’s masculinity would become a central tenet of their relationship. And while Hemingway certainly performed and exaggerated his machismo identity, there were distinct differences between the two men and their personalities that exacerbated this dynamic. Fitzgerald wrote lyrical, descriptive prose to Hemingway’s sparse minimalism. Fitzgerald summered on the beaches of the French Riviera while Hemingway watched bullfights in Spain. Fitzgerald preened and pretended to be wealthier than he was, while Hemingway affected a modest poverty that was far less than he actually made; though Hemingway’s wife had a sizeable trust fund, he used to say that he had to catch pigeons in the public park to eat for dinner.

There was another distinct difference between the two men that impacted their relationship: their drinking habits. While both were big drinkers, Fitzgerald would get hammered after a few cocktails and pass out, or worse, grow mean and insult his friends. Hemingway was a devoted alcoholic but could drink multiple bottles of wine without ever showing it. Later in their relationship, Hemingway would grow irritated with Fitzgerald’s drunken antics and refuse to tell him his address, only meeting up with him at cafes and restaurants. He saw Fitzgerald’s inability to hold his liquor as an indicator of his supposedly weaker, more feminine nature.

In June 1926, Fitzgerald got roaring drunk at a party that their mutual friends—Gerald and Sarah Murphy—were throwing to welcome Hemingway and his wife to the French city of Antibes. Fitzgerald, perhaps jealous of the attention paid to Hemingway, threw ashtrays at the other tables. In 1933—feeling insecure over the success of Hemingway’s 1929 novel A Farewell to Arms compared with his own stagnating career—Fitzgerald crashed a dinner between Hemingway and Edmund Wilson and got so drunk that he laid down on the floor of the restaurant and the pair had to help him to the bathroom so he could vomit. In between bouts of puking, he asked his annoyed friends if they still liked him.

Another important difference was the pair’s working habits. Fitzgerald, at the height of his career, could charge a significant sum for his short stories which he sold to The Saturday Evening Post, which had a readership of three million. Hemingway considered these pop culture-style stories to be cheap trash and a squandering of Fitzgerald’s talent. In 1935’s The Green Hills of Africa, Hemingway wrote about writers who “when they have made some money increase their standards of living and they are caught. They have to write to keep up their establishments, their wives, and so on, and they write slop.” While Fitzgerald would ultimately agree with Hemingway, he continued writing short stories to maintain his lifestyle and later, pay off his debts.

Still, in many ways, it was Fitzgerald who elevated and supported Hemingway’s career. Fitzgerald introduced Hemingway to his publisher, Charles Scribner’s Sons, and his editor, Max Perkins. In 1924, he wrote to Perkins saying, “This is to tell you about a young man named Ernest Hemingway who lives in Paris…and has a brilliant future…I’d look him up right away, he’s the real thing.”

Fitzgerald saw Hemingway’s writing as confident and effortless—two traits he felt his own work lacked. He later wrote to Perkins, that “I told [Hemingway] that against all logic that was then current, that I was the tortoise and he was the hare, and that’s the truth of the matter, that everything I have ever attained has been through long and persistent struggle while it is Ernest who has a touch of genius which enables him to bring off extraordinary things with facility.”

Hemingway repaid Fitzgerald’s kindness and support with nothing short of cruelty. His 1964 memoir, A Moveable Feast, which documents his years in Paris, portrayed Fitzgerald (who was then dead and couldn’t defend himself) as weak, cowardly, and insecure, and Hemingway exaggerated or completely altered some of their time together. In June 1925, after taking a road trip together, Hemingway wrote to Perkins that “Scott Fitzgerald is living here now and we see quite a lot of him. We had a great trip together driving his car up from Lyon through Côte d’Or.” In A Moveable Feast, Hemingway describes this same road trip with paternalistic contempt, in the words of biographer Jeffrey Meyers, characterizing Scott as “hostile to the French, childish and gauche, wasteful and irresponsible, quarrelsome and irritating, hypochondriac and insecure, dependent upon and dominated by Zelda, a complacent and self-confessed cuckold, a drunkard and artistic whore, a destroyer of his own talent.”

Zelda would become another point of contention in the pair’s relationship. She saw through Hemingway’s show of manliness and told him, “No one is as masculine as you pretend to be.” She reportedly once said that The Sun Also Rises was about “bullfighting, bullslinging, and bullshitting.” Hemingway thought Zelda was pathologically jealous of Scott’s success and was at least partially responsible for his failures, telling Scott, “Of all people on earth, you needed discipline in your work and instead you married someone who is jealous of your work, wants to compete with you and ruins you.”

Zelda and Scott’s relationship would also be the subject of Hemingway’s most mean-spirited posthumous dig at his old friend. After trying and failing to have a second child in the winter of 1926, Zelda accused Hemingway and Fitzgerald of being gay and insulted the size of Scott’s penis. While Scott very well may have spoken of these anxieties with Hemingway, Hemingway, in turn, further exaggerated them in a now-notorious passage of A Moveable Feast.

According to Hemingway, Fitzgerald confessed, “You know I never slept with anyone except Zelda…Zelda says the way I was built could never make a woman happy,” and asked Hemingway to come to the bathroom with him to inspect the size of his penis. Hemingway agreed, and when asked by Fitzgerald to “tell him truly,” told him, “You’re perfectly fine. You are O.K. There’s nothing wrong with you.”

If this was true, it would have been a monumental betrayal of Fitzgerald’s confidence, but Fitzgerald wrote in his “The Crack-Up” essays in 1936 that he had been with a prostitute while a student at Princeton and with the English actress Rosalie Fuller two years later. Moreover, scholars have pointed out that the phrase “tell me truly” is much more aligned with Hemingway’s manner of speech than Fitzgerald’s. This anecdote aligns with Hemingway’s beliefs about Scott’s masculinity and Zelda’s role in his decline, and should be taken with a few grains of salt.

Hemingway also downplayed the degree to which he respected Fitzgerald as a writer. In the early years of their friendship, the pair edited one another’s work, shared story ideas, and debated literary styles late into the night. Hemingway wrote in A Moveable Feast that Fitzgerald was hurt he never shared the manuscript of The Sun Also Rises with him prior to its publication, when in fact, Fitzgerald had read and revised it. Hemingway even took Fitzgerald’s suggestion to cut the first two chapters.

Hemingway also expressly admired Fitzgerald’s craftsmanship in The Great Gatsby, and the line “Then I went out of the room down the marble steps into the rain,” is believed to have directly inspired the closing line of A Farewell to Arms: “After a while I went out and left the hospital and walked back to the hotel in the rain.”

In the long nine years in between Fitzgerald’s publication of The Great Gatsby and Tender Is The Night, Hemingway gave him much-needed encouragement, saying, “You just have to go on when it is worst and most [hopeless]—there is only one thing to do with a novel and that is go straight on through to the end of the damn thing.”

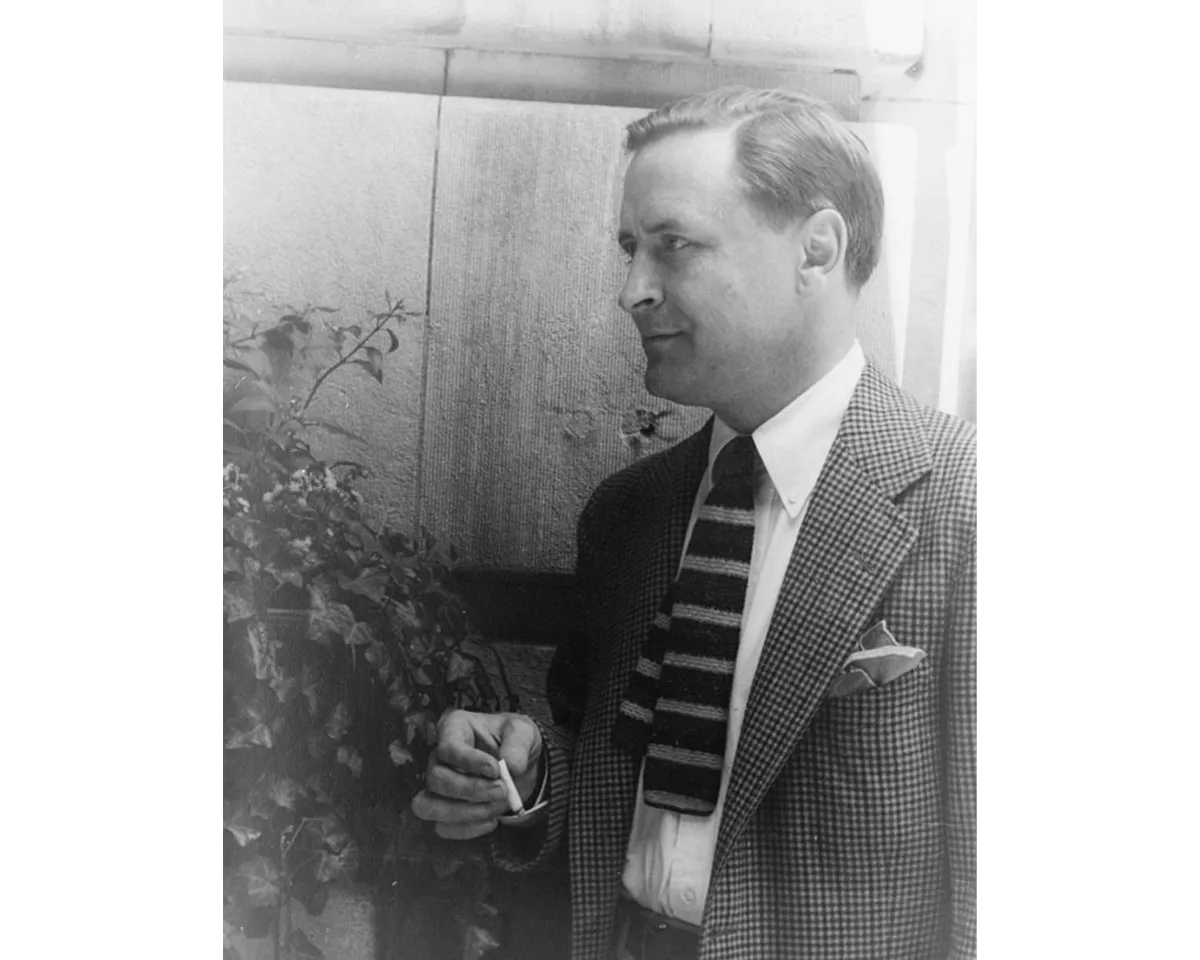

The rift between them grew wider, however, when Fitzgerald published his confessional “The Crack-Up” essays in Esquire in 1936. The essays—in which Fitzgerald publicly excavated his alcoholism and mental breakdown with courage and honesty—offended Hemingway, who thought Fitzgerald was demeaning himself. For Fitzgerald, who had made himself completely vulnerable, Hemingway’s disapproval was only worsened when he insulted Fitzgerald in his short story “The Snows of Kilimanjaro.” The pair never truly made up before Fitzgerald died in 1940, although he did write Hemingway a kind letter on the publication of For Whom the Bell Tolls, saying, “I envy you like hell and there’s no irony in this.”

In their tragic deaths, the pair found another thing in common. Despite getting sober in the final year of his life, Fitzgerald’s alcoholism left him dead of a heart attack at only 44. While Hemingway lived until he was 61, his high tolerance for alcohol finally failed him, and he began displaying the very drunken behavior he had previously hated in Fitzgerald. In what many scholars now believe to be the result of multiple instances of head trauma, Hemingway rapidly lost the faculties he once prided his masculine identity on and shot himself in 1961.

While Hemingway and Fitzgerald’s friendship was an often competitive, petty, and mean-spirited one, their enduring relationship and shared interest in one another’s work indicate a mutual admiration and respect (even if Hemingway would deny this). And while Hemingway was no doubt the more successful in life, perhaps Fitzgerald got the final word, in that today’s literary canon has reunited the old friends, putting their works side by side.

For More Information:

Blume, Lesley, Everybody Behaves Badly: The True Story Behind Hemingway's Masterpiece the Sun Also Rises, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Donaldson, Scott, Hemingway vs. Fitzgerald: the Rise and Fall of a Literary Friendship, Harry N Abrams, 1999.

Meyers, Jeffrey, F. Scott Fitzgerald: A Biography, Harper Collins, 1994.

.webp)