Today, few American children turn 18 without reading F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. It is regarded as the American novel, crucial to not only our public education system but also how we conceptualize ourselves and our national identity within the realm of literature. There is also significant speculation on the “real” Gatsby and the inspiration behind the novel’s iconic characters and settings. This speculation is warranted, as Fitzgerald did pull heavily from his own life. To get a better sense of his literary masterpiece, we’ll explore the equal parts stunning and saddening life of F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Fitzgerald was born Frances Scott Fitzgerald in 1896 in Minnesota. He was named after the famed Frances Scott Key, a distant relative of his father’s who is known for writing The Star Spangled Banner. This fact reveals a crucial dynamic that was present throughout Scott’s life. His father’s family were multiple generations Marylanders and were extremely proud of their old American identity. And while they used to be wealthy, by the time Scott was born his father was quite poor. His mother’s family were first-generation Irish immigrants but had grown wealthy and successful. This dynamic of old American identity paired with poverty, and new immigrant identity paired with wealth, gave Scott a profound anxiety about his class and sense of self, something that would appear consistently throughout his work and is central to The Great Gatsby.

Scott first began writing plays and poetry while a college student at Princeton. He was so dedicated to his literary craft that he completely disregarded his academic studies and failed multiple classes. He took a leave of absence from school in 1917, claiming it was due to a flair-up of Tuberculosis, but was really a result of poor grades. Scott took this time to enlist in the military. World War I had begun in 1914 and he was eager to participate in the defining geopolitical conflict of his generation.

Unfortunately for Scott’s ego (although fortunate for his well-being) he was never sent overseas and spent the remainder of the war stationed in Alabama. Scott’s lack of service in Europe further cemented his inferiority complex, and it is worth noting that in The Great Gatsby, both Nick and Gatsby spent time serving in France during WWI.

What he lost in valor, he made up for in love, for it was in Alabama that Scott would meet Zelda Sayre, the beautiful, wealthy, and wild daughter of a judge. Most people assume Zelda to be the inspiration for Gatsby’s femme fatale love interest, Daisy Buchanan, and Scott borrowed Zelda’s mannerisms, behavior, and even directly quoted her to create the shimmering, opulent Daisy. Yet he cites an earlier love interest he met in Chicago, Ginevra King, as being the foremost influence.

Scott was attracted to beautiful, wealthy, and charismatic women, and the 17-year-old Zelda was all three. She had no interest in the old Victorian rules of propriety and lived according to her own, often flamboyant, moral code. She loved parties and dancing and was often flippant with the wealth of male attention she received. Scott was completely enchanted by her. They got engaged in 1918 and Scott left for New York City to try to make it as a writer.

He lasted five months in New York working as an advertisement writer, during which Zelda called off their engagement, concerned at Scott’s ability to provide for her. Heartbroken and disappointed, Scott moved back to Minneapolis. It was there, in his parent’s attic, that he would write the novel that catapulted his career, This Side of Paradise.

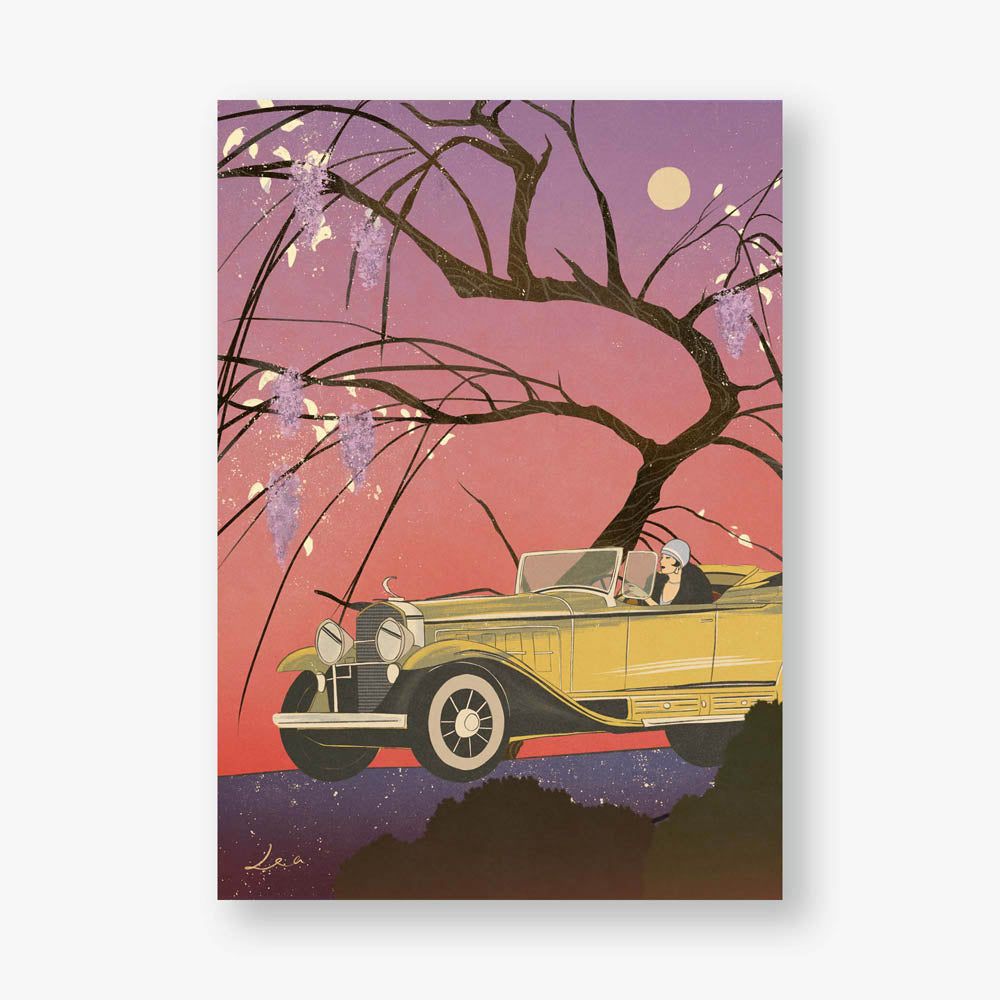

This Side of Paradise was not a timeless novel like Gatsby, but a perfect encapsulation of the late 1910s, and early 1920s, and the restless and rebellious generation that was coming of age at that time. It was published by Scribner in 1920 and became an instant success. We often think of Scott as the premier writer of the Jazz Age, which he is, but he also quite literally defined the language used to describe the period, coining the very term The Jazz Age as well as Flappers. Awash with fame and money, he and Zelda rekindled their love and were married in April of 1920.

These first years of his and Zelda’s marriage were wild and wonderful, and they lived according to the reputation Scott’s literature had established for them. They were outrageous: they hotel-hopped, often getting kicked out due to noise complaints. Upon getting evicted from the Biltmore, they spent a half hour running through the revolving door. Zelda became a famed wild child when she jumped fully clothed into the fountain at Union Square. They partied late into the evenings and drank copiously.

In 1921, Scott’s second novel, an eerily prescient tale of a collapsing marriage and a man’s descent into alcoholism, The Beautiful and Damned was serialized and eventually published as a full novel. Zelda became pregnant in 1922, and the couple moved back to Minnesota for the birth of their only child, a daughter they called Scottie.

In 1923, Scott and Zelda moved to Great Neck, Long Island to allow him to better focus on his work. There, he began plans for a third and more “serious” novel. He no longer wanted to be a documentarian of his generation, but to be known for something timeless and profound. He carefully studied James Joyce’s Ulysses and Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness for their stylistic sophistication.

This work would be his magnum opus. Originally titled Trimalchio in West Egg, he finally settled on The Great Gatsby.

A letter to his editor, Max Perkins, reveals the intensity of Scott’s ambitions during this period: “I cannot let it go out unless it has the very best I’m capable of, or as I feel sometimes, much better than I’m capable of…In my new novel I’m thrown directly on purely creative work–not trashy imaginings as in my stories but the sustained imagination of a sincere and yet radiant world. So I tread slowly and carefully + at times with considerable distress. This book will be a consciously artistic achievement + must depend on that as the first books did not…Please believe me when I say I’m doing the best I can.”

Finding that Long Island still provided too many distractions, in 1924 Scott, Zelda, and Scottie moved to the French Riviera. With Scott spending long hours writing and the nanny watching Scottie, Zelda spent days alone on the beach, bored and craving attention. Soon after, she began an affair with the aviator Edouard Jozan. What follows next is unclear, some scholars believe Zelda asked Scott for a divorce so she could be with Jozan, only for Jozan to abandon her. What we do know, is that a week later Zelda had her first unsuccessful suicide attempt, in which she took a near-fatal dose of sleeping medication. This sequence of events shattered Scott’s trust and perhaps inspired the multiple infidelities in Gatsby, both Tom with Myrtle, and Daisy with Gatsby.

The Great Gatsby was published in April 1925, but contrary to Scott’s expectations, it did not perform well. While he received positive reviews from his friends and peers, its critical reception was mixed and it sold poorly. While technically, Gatsby has never been out of print, that is only because Scribner was unable to sell the 3,000 copies in the novel’s second printing. These books would stay in a Scribner warehouse until after Scott’s death.

The Fitzgeralds left the Riviera in 1925, largely to escape the ghost of Zelda’s infidelity. They settled in Paris and became part of the Lost Generation, a group of expat writers such as Ernest Hemingway and Gertrude Stein. The Lost Generation was shaped by their experiences in the war and rejected religion and Victorian social mores in favor of cynicism and debauchery.

Throughout this period Scott and Zelda’s marriage worsened. He was still hurt from her infidelity and her mental health never fully recovered from her suicide attempt. In the Spring of 1929, Scott was driving to Paris with Zelda & Scottie when Zelda attempted to grab the steering wheel and drive the family off a cliff. This incident led to Zelda’s diagnosis of schizophrenia, which would result in her being in and out of sanitariums for the rest of her life.

With Zelda receiving expensive treatments in Europe and the United States, and Scottie attending boarding school, Scott wrote short stories to provide for his wife and daughter. These stories were unsophisticated and had to fulfill the public’s tastes for drama, but Scott was able to sell them for a high price. Still, he consistently fell into debt, owing large sums of money to both Max Perkins and his editor, Harold Ober. He wanted to write another novel inspired by Zelda’s mental health treatment (this would eventually become Tender Is the Night) but his mounting debts meant he largely had to focus on his short stories.

Tender is the Night was released in 1934 to poor sales and reviews, with many not understanding the novel’s unconventional structure, which jumps back and forth through time. During this period of isolation, Scott’s alcoholism worsened. He made very little off royalties and lived out of cheap hotels where he would write for hours, drinking copious amounts of alcohol that destroyed his health. During his brief periods of sobriety, he would quell the cravings by guzzling Coca-Cola and eating mountains of sweets. From 1933-1937 Scott was hospitalized eight times for alcohol-related health complications.

A 1936 interview reveals the collapse of Scott’s mental health and sense of confidence: “The reporter asked Mr. Fitzgerald about how he felt now about the jazz-mad, gin-mad generation whose feverish doings he chronicled… ‘Some became brokers and threw themselves out of windows. Others became bankers and shot themselves. Still others became newspaper reporters. And a few became successful authors.’ his face twitched. ‘Successful authors!’ he cried. ‘Oh, my God, successful authors!’ He stumbled over to the highboy and poured himself another drink.”

Like Gatsby, who began as a golden success, Scott had fallen into tragedy and disrepair. While he was briefly given a second chance at success through working as a Hollywood scriptwriter, he struggled to remain sober and sacrifice his artistic ideas to the whims of the studios. He died in 1941 of a heart attack, he was only 44 years old.

Scott died believing himself to be a failure. In those later years, he averaged only $30 in royalties and his books had gone out of print. For all intents and purposes, he had been largely forgotten. Yet the mid-1940s saw a rekindled interest in Gatsby, and by 1950 there was a full-blown Fitzgerald Revolution taking place in the world of American letters.

Today, you would be hard-pressed to find a single individual in the United States who has not read The Great Gatsby and has been moved by Fitzgerald’s vivid characters and shockingly beautiful language. In the end, Fitzgerald was a successful author indeed.

For more information check out…

Broccoli, Matthew and Bryer Jackson, F. Scott Fitzgerald: In His Own Time, Popular Library, 1971.

Corrigan, Maureen, So We Read On: How The Great Gatsby Came to Be and Why it Endures, Little Brown & Company, 2014.

Meyers, Jeffrey, Scott Fitzgerald: A Biography, Harper Collins, 1994.