There are many books in this world, some are good, and even fewer are great, but only a handful are truly transformative. The number of authors who can claim work so revelatory as to permanently alter the literary canon is a small and precious few. But among their ranks, without a doubt, is the inimitable Mary Shelley, author of the first known work of science fiction and a book that has haunted our collective culture for over 200 years, Frankenstein.

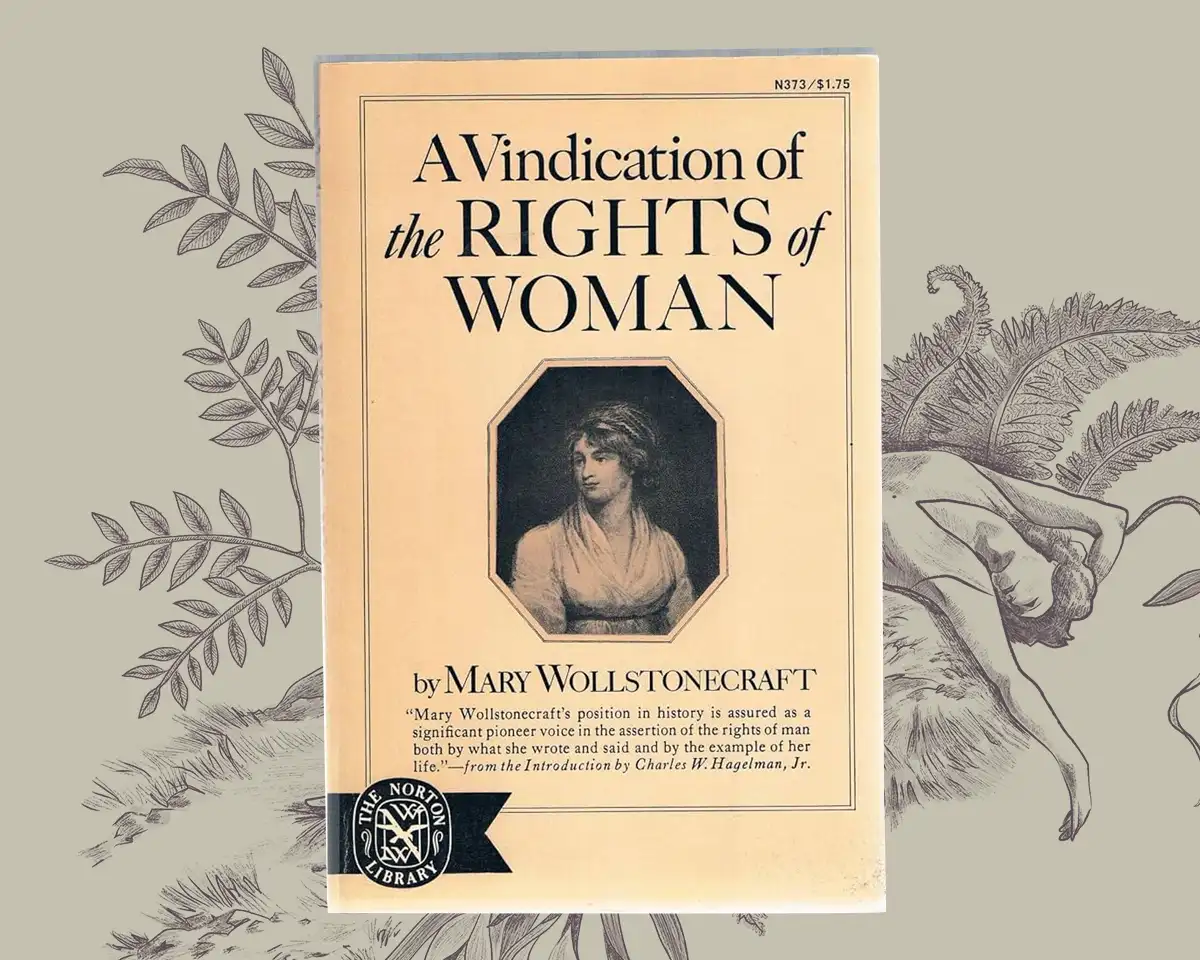

From the moment of her conception, Mary Shelley was never going to be a normal woman or even a normal writer. The literary gods had blessed her with two incredibly talented parents. Her father, William Godwin was a philosopher and political thinker credited with the popularization of anarchy. Her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, created one of the earliest feminist tracts with her trailblazing A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Moreover, recent research from literary scholars has identified Wollstonecraft’s later writing as being an early iteration of Romanticism.

Wollstonecraft and Godwin’s courtship was a quick one. They loved each other deeply but believed that marriage was an unethical institution akin to slavery. However, they bit the bullet when Wollstonecraft got pregnant and married, causing a scandal in late 18th-century London. On August 30th, 1797, Wollstonecraft gave birth to a gorgeous baby girl, who they named Mary. For a few precious days, the little family was happy: Wollstonecraft, Godwin, Mary, and her three-year-old half-sister Fanny Imlay, who was Wollstonecraft’s daughter with another man. Tragically, Wollstonecraft would die ten days after giving birth due to a post-partum infection.

Wollstonecraft cast a large shadow over young Mary’s childhood. The little girl learned to read by tracing the letters on her mother’s headstone, a large portrait of her mother hung in her father’s study, and Wollstonecraft’s admirers (Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Wordsworth, and Americans John Adams and Aaron Burr to name a few) paid homage by visiting their household and seeing the little girl who was destined for literary greatness. When Mary was old enough, she would read all her mother’s published works many times over.

Four years later, Godwin remarried, bringing a new wife and her three new children into the family. Mary resented the change, she and her father were incredibly close and she did not like having to share him. Her relationship with her stepmother was fraught, and her step-sister Claire Clairmont was often jealous of Mary. At fifteen, Mary was sent to the seaside town of Ramsgate, and then later to Scotland to live with old friends of her mother’s. Godwin claimed this was to cure a bout of eczema Mary was suffering, but the true reason likely lay in the strain between Mary and Godwin’s new family. This was the first crack in what would become a profoundly painful break between father and daughter.

Mary returned to London two years later. One night, her father invited over a young poet named Percy Bysshe Shelley. Percy was another Wollstonecraft devotee, and Godwin was hoping the young man could help him out of his accumulating debts. Instead, Percy would run away with not one, but two of Godwin’s daughters.

Percy was already married, but he was utterly enchanted by Mary. To him, she was the beautiful, intelligent daughter of one of his favorite writers. To her, he was the handsome, passionate poet who could help her escape her fractured family. Mary took him to her most special place, Wollstonecraft’s tombstone, where the pair confessed their love and perhaps did even more. They then ran away to Paris together where they eloped, taking with them Mary’s half-sister Claire. Godwin was furious, and when they returned to London he refused to speak with Mary, except to ask her and Percy for money.

Mary and Percy were intellectually compatible and emotionally tied, and the first few years of their relationship were filled with excitement. They debated literature and philosophy, read aloud to one another from Wollstonecraft’s books, and even shared a diary. Yet, even within her marriage Mary was at times excluded. Claire’s presence grated on Mary, and it didn’t help that her step-sister and husband grew increasingly close, with some scholars suggesting their relationship was more than platonic. This was sadly only the beginning of Mary’s struggles, in 1815, at only 17 years old, she prematurely gave birth to a little girl, who died less than two weeks later.

In 1816, Mary gave birth to a little boy named William, but the year was not a wholly good one. Two more tragic deaths shook the small family. Mary got word that Fanny had committed suicide, and only a few months later, Percy learned his first wife Harriet had also killed herself. Mary, still barely an adult, was wracked with grief and guilt. When baby William developed a lingering cough, Mary, Percy, and Claire quit the smoke and smog of London and headed to Switzerland.

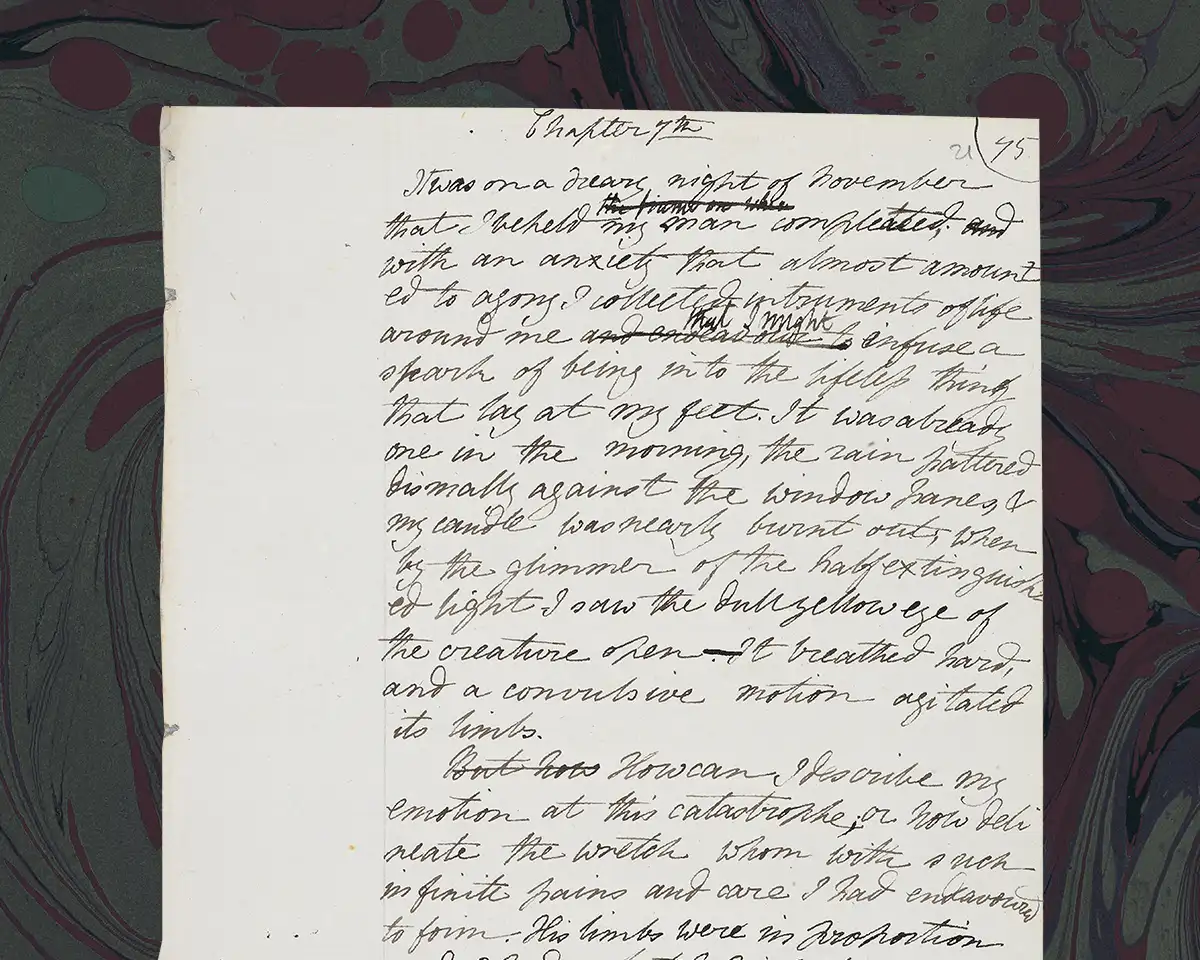

They chose Switzerland because of news that the famous poet Lord Byron would be vacationing there. Percy greatly admired Byron, who was the far more successful poet, and Claire had a major crush on him. In the summer of 1816, they met up with Byron and his personal doctor, John Polidori, and they all lived together in Villa Diodati on the shores of Lake Geneva. It was here that Mary would begin writing Frankenstein.

The vacation in Geneva, while great for creative inspiration, was a bust in terms of tourist activities. That summer a volcano had erupted in modern-day Indonesia, causing unseasonably cold and stormy weather across Europe. Mary was stuck indoors with Claire and Byron’s constant flirting and she was followed around incessantly by John Polidori, who was infatuated with her. Getting on each other’s nerves, Byron suggested the group have a ghost story writing competition. Mary, only 18 years old, began writing and didn’t stop.

Frankenstein is a novel undoubtedly born from grief. Mary captures the grief she felt over the early loss of her mother, the abandonment of her father, the guilt and shame she held over Fanny and Harriet’s suicides, and the devastating loss of her baby. Grief leaks from the pores of the novel, it saturates its every page. The public would come to know the loss and darkness that consumed Mary, and it captivated and disturbed them as it has captivated and disturbed us.

After Geneva, Percy and Mary moved to Italy where they celebrated the birth of a second daughter, Clara. Sadly, the Shelleys’ joy was short-lived, as Clara died in late 1818, and William died nine months later. Mary was devastated, writing, “The world will never be to me again as it was—there was a life & freshness in it that is lost to me….”

Percy felt the gulf of grief that had grown between him and his wife, writing: “My dearest Mary, wherefore hast thou gone, and left me in this dreary world alone?”

In 1819, Mary gave birth again to Percy Florence, the only child of the Shelleys to live to adulthood. However, her greatest tragedy was yet to come. Her husband was prone to dreams of grandeur, dreams that didn’t always hold up in the material world. In the 1820s he became obsessed with sailing, and in 1822, after going for a boat ride in his own poorly constructed vessel, drowned.

Mary was understandably inconsolable. While hers and Percy’s relationship was complicated and often punctuated with long periods of silence, he was her partner, her creative counterpart, and the father to her only living child. In moments of strife, Percy had not spoken positively of Mary to his friends, and after his death, their social circle withdrew. Some of his friends even stole Percy’s actual heart once his body had washed ashore. Mary wanted to stay in Italy, but her father-in-law refused to support her unless she and young Percy came back to England.

In the Introduction to Frankenstein’s third edition published in 1831, Mary writes: “[this book] was the offspring of happy days, when death and grief were but words, which found no true echo in my heart. Its several pages speak of many a walk, many a drive, and many a conversation, when I was not alone; and my companion was one who, in this world, I shall never see more.”

While calling Frankenstein “the offspring of happy days” is perhaps influenced by the rose-colored glasses of nostalgia, we cannot blame Mary for thinking of it as a happier time and book than it was. As she became older her writing grew even darker and more pessimistic. Her 1826 novel, The Last Man, takes the essential message of Frankenstein: that isolation leads to danger and death, that survival and happiness can only be found in community, and applies it to a global scale through a pandemic that decimates the earth’s human population. In addition to her own writing, she was a careful and considerate steward of Percy’s writing.

Mary passed away in 1851, with her son and daughter-in-law at her side. By 19th-century standards, she lived to the wizened old age of 53.

Yet her seminal novel would go on to live a much longer life. Fascinatingly, in tracking attitudes toward Mary Shelley and Frankenstein we can track the progress of modern feminism and the rediscovery of the work of so many scribbling women. In the decades that followed Mary’s death, her work largely faded into obscurity. Percy was considered the real star of their marriage, and perhaps due to Mary’s advocating for his work, he became a critical member of the canon of Romantic writers. If people did talk about Mary and Frankenstein, they spoke solely of Percy’s influence.

This only began to change in the 1970s, when second-wave feminist scholars reanimated Mary Shelley’s novels and began considering them not as the dark daydreams of a poet’s wife, but for their own distinct perspective and message.

During the past two years, I have read Frankenstein for the second, third, fourth, and even fifth time. It never ceases to amaze me, scare me, and inspire me. It is a novel that is both incredibly mature and indicative of the anxieties and fears of a very young girl. Moreso, as I have learned more about Mary’s life, I am consistently struck by her tenaciousness, her intelligence, and frankly, her weirdness. Not only was she a woman writer at a time when doing so practically unheard of, but she wrote about topics that disturbed, horrified, and taught us fundamental lessons about how we treat one another. She singlehandedly created the genre of science fiction, and dared to write dark and inventive stories far outside the safe topics of love and marriage.

These days, Mary Shelley is all around us: from Margaret Atwood to Carmen Maria Machado, Poor Things to The Last of Us. She lives on our modern debates about technology, science, feminism, and environmentalism. She lives on in me, and all the many young women who scribble strange stories.

Happy Birthday Mary. I loved you at 18 and I love you at 27. Thank you for all the nightmares.