Few writers have proved so radical and transcendent as to reshape the way we think about literature, and by extension ourselves and our world, as Virginia Woolf.

From the modernist masterpiece that is To the Lighthouse (1927) to her feminist treatise A Room of One’s Own (1929), Woolf rejected the neatly organized plots of traditional Victorian literature in favor of novels that called us to investigate our own human interiority, and how our subjective experience interacts with the objective reality of the world around us.

No book captures this dynamic more than her 1925 novel, Mrs. Dalloway. Indeed, Mrs. Dalloway is a novel that defies basic summary (but we’ll do our best to describe it).

Set during a single June day in 1923, it tells the story of two central characters: Clarissa Dalloway, a sensitive socialite, and Septimus Smith, a shell-shocked war veteran. Clarissa and Septimus barely interact, yet their parallel narratives serve as explorations of sanity and insanity. For them both, mundane events, like Clarissa’s decision to purchase flowers that open the novel, trigger explorations of their past and current psychological states. The novel ends with Clarrissa throwing a party and Septimus committing suicide, their stories briefly overlapping when the doctor who treated Septimus arrives at Clarrissa’s party and announces his death.

Mrs. Dalloway’s stream-of-consciousness structure captured a poignant reality: that we are not simply characters to whom a series of events happen, but individuals composed of memories, emotions, and sensory experiences that emerge constantly throughout our daily lives. Woolf believed strongly that human beings are not composed of one single identity, but are a multitude of varying states and experiences. Clarrissa and Septimus can be seen as embodiments of Woolf’s own contradictions: her polished social self vs her inner mental turmoil. So who was Virginia Woolf, and what does her life reveal about her incredible art?

Adeline Virginia Stephen was born in 1882 to affluent Victorian parents. Her father, Leslie Stephen was a literary figure and editor, and her mother, Julia Jackson was a former model.

Both parties had been previously married and brought children to the marriage. Leslie had one child with his first wife, and Julia had three with her late husband Herbert Duckworth. Together Leslie and Julia had four children: Vanessa, Thoby, Virginia, and Adrian.

For Virginia, this expansive family (three full siblings and four step-siblings) was not always a happy one. As an adult, she would write about childhood sexual abuse she experienced at the hands of her half-brother George Duckworth. When she was 13, her mother died, and two years later so did her half-sister Stella Duckworth. When her father died seven years later in 1904, Virginia experienced her first mental breakdown. Virginia’s oscillating mental states, from periods of happiness and productivity to near-catatonic states of depression and suicidal ideation, would plague her for the rest of her life.

After their father’s death, Vanessa moved her younger Stephens siblings to the Bloomsbury neighborhood of London, a bohemian enclave for radicals and artists. Full of artistic ambitions, Vanessa, Thoby, Virginia, and Adrian would host groups of radical young people to dinner where they debated and exchanged ideas.

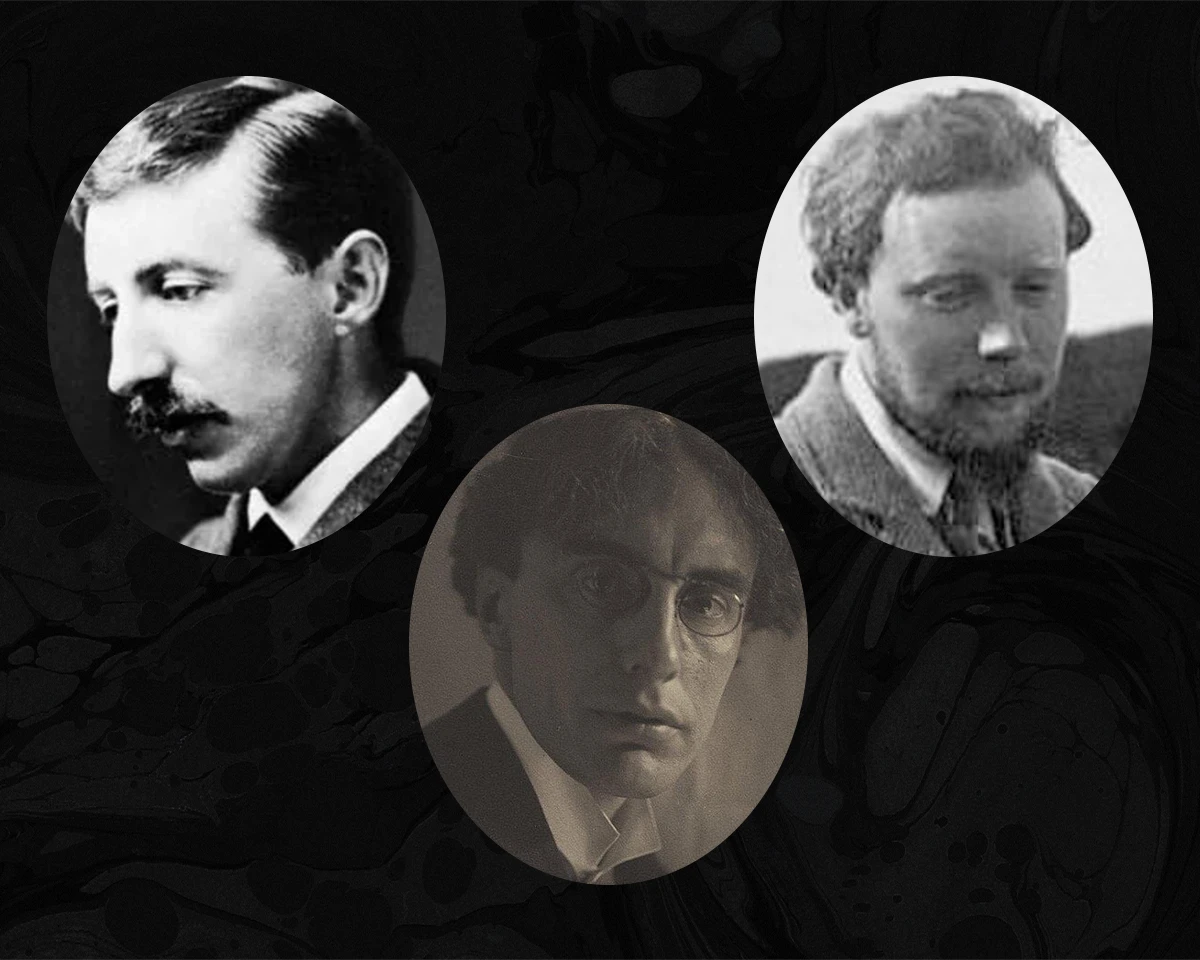

Frequent guests were E.M. Forster, Clive Bell, Roger Fry, and Leonard Woolf, together they became known as the Bloomsbury group.

It was among this community that Virginia encountered modernism for the first time: a literary style that strove to change the way how reality was portrayed. Staples of modernism appear consistently in Woolf’s work, including stream of consciousness, shifting perspectives, distortions of time, and interior monologues.

In 1906 after a family vacation to Greece, Thoby died of Typhoid fever. This loss was compounded by the fact that Vanessa got engaged to Clive Bell. But this time, instead of slipping into depression, Virginia began to write, using it as a tool to navigate these changes.

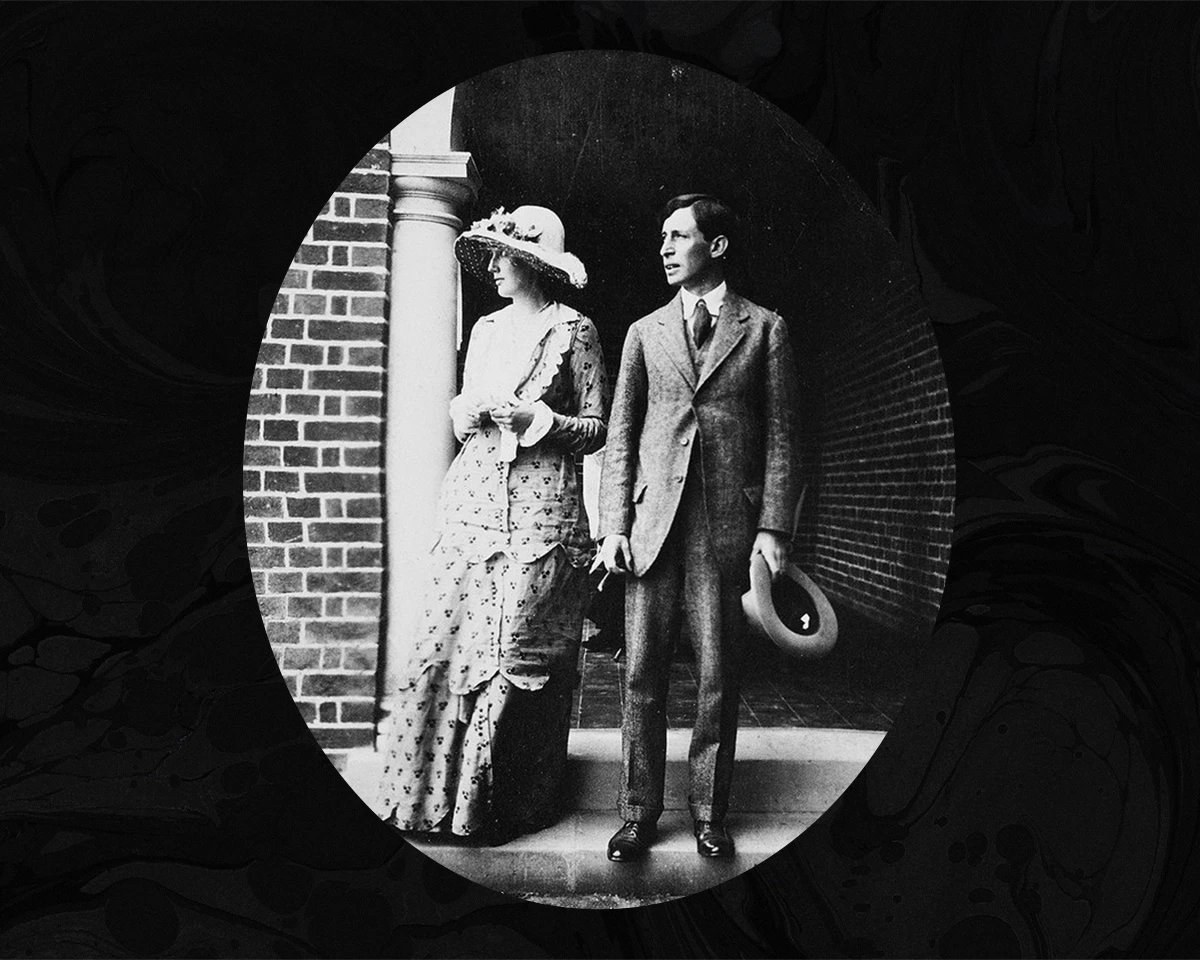

In 1912 she married Leonard Woolf and shortly after, they left Bloomsbury for the suburbs.

Still, Virginia struggled with her mental health. In 1913, on the eve of the publication of her first book The Voyage Out, Virginia became convinced that her sister and husband both hated her and attempted suicide. The publication was delayed until 1915 when she was able to sufficiently recover.

In 1917, she and Leonard bought a printing press and founded Hogarth Press in their living room. As Woolf’s writing grew increasingly experimental, she and Leonard would publish her books themselves. Today, Hogarth is a publishing imprint of Penguin Random House.

In 1924, she and Leonard moved back to Bloomsbury, where Virginia would begin the most significant of several lesbian affairs. Her relationship with the novelist Vita Sackville West, while often fraught, was deeply intimate.

It also informed much of Woolf’s radical writing on gender and sexuality. Her gorgeous queer text Orlando (1928) is a love letter to Vita, casting her as the nobleman Orlando who chooses to become a woman. In A Room of One’s Own Virginia wrote: “It is fatal to be a man or woman pure and simple. One must be woman-manly or man-womanly.”

It was also during this period in Bloomsbury that she would write Mrs. Dalloway, a novel that synthesized her brilliant ideas regarding literary forms and human interiority. She was inspired to write Mrs. Dalloway after reading James Joyce’s Ulysses, a novel that similarly distorts time by taking place entirely during one day and centers around mundane circumstances that coincide with inner revelations.

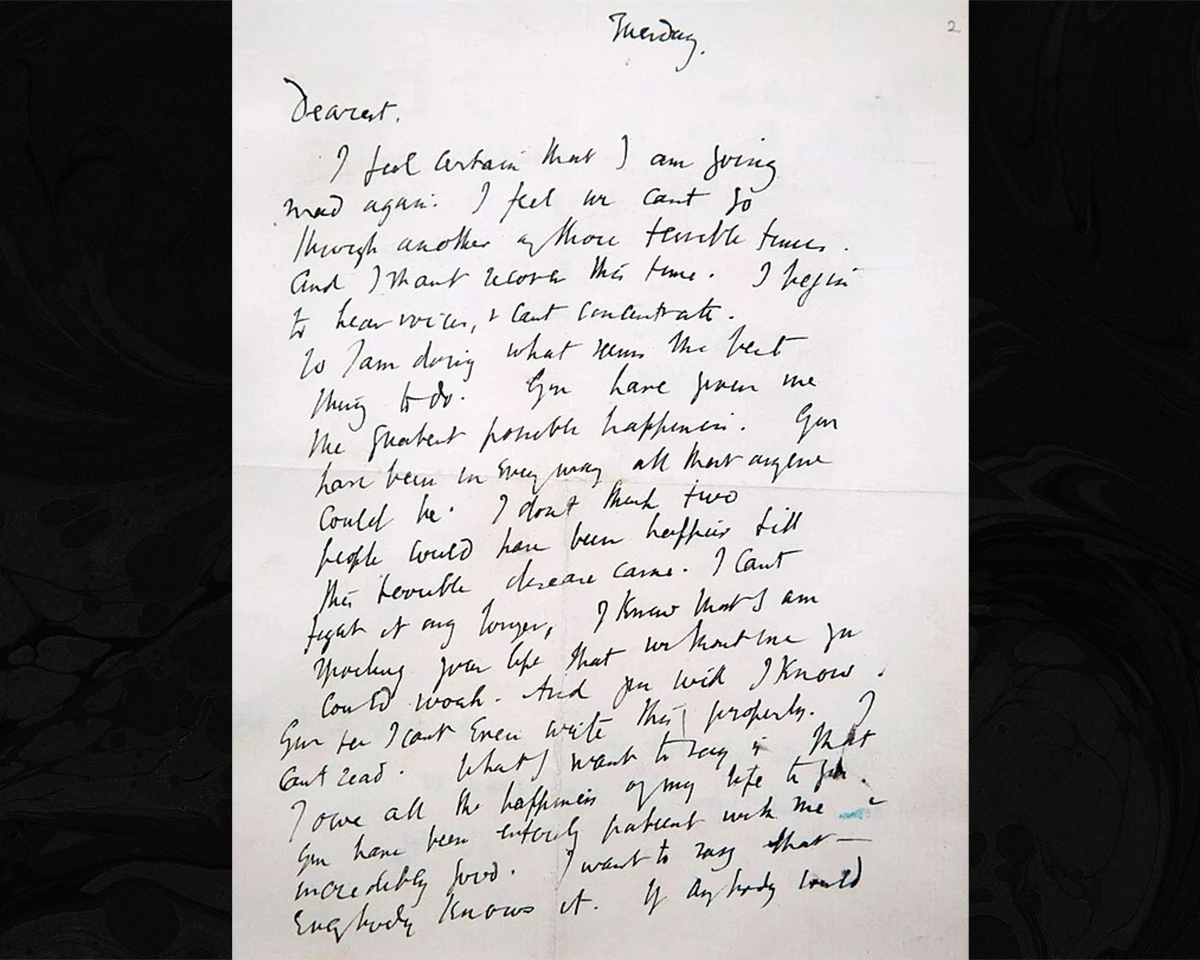

Tragically, Mrs. Dalloway would also foreshadow Virginia’s own death. Like Septimus whose narrative ends with his suicide, in 1941, shortly after the onset of World War Two, Virginia would fill her pockets with rocks and walk to the river Ouse, near the home in Essex she and Leonard had moved to. She stepped into the river and never emerged. She left behind this heartbreaking letter to Leonard:

“Dearest,

I feel certain I am going mad again. I feel we can’t go through another of those terrible times. And I shan’t recover this time. I begin to hear voices, and I can’t concentrate. So I am doing what seems the best thing to do. You have given me the greatest possible happiness. You have been in every way all that anyone could be. I don’t think two people could have been happier till this terrible disease came. I can’t fight any longer. I know that I am spoiling your life, that without me you could work. And you will I know. You see I can’t even write this properly. I can’t read. What I want to say is I owe all the happiness of my life to you. You have been entirely patient with me and incredibly good. I want to say that — everybody knows it. If anybody could have saved me it would have been you. Everything has gone from me but the certainty of your goodness. I can’t go on spoiling your life any longer.

I don’t think two people could have been happier than we have been.”

While Mrs. Dalloway ends with Clarissa sympathizing with Septimus and even understanding his decision, this same empathy was not granted to Virginia. The British public lambasted her death as an act of unpatriotic cowardice rather than a choice made by a profoundly ill woman.

Despite the trauma and sickness that plagued so much of Virginia’s life, she left behind a treasure trove of genius and insight. Not only were her novels wholly inventive in their style, structure, and the deep consideration they gave to the inner lives of her characters, but queer and feminist texts such as Orlando and A Room of One’s Own would inspire scholars and writers for generations to come. Orlando’s gender-bending was decades ahead of its time, and A Room of One’s Own would become a foundational feminist text, calling us to question how many genius women writers were stifled by their circumstances."

Most of all, Virginia left us with a powerful legacy of observation, teaching us through texts like Mrs. Dalloway that no details are too small to be worthy of notice and no events too domestic to be deserving of a place in literature.

For more information read…