“In an old house in Paris

That was covered in vines

Lived twelve little girls in two straight lines.”

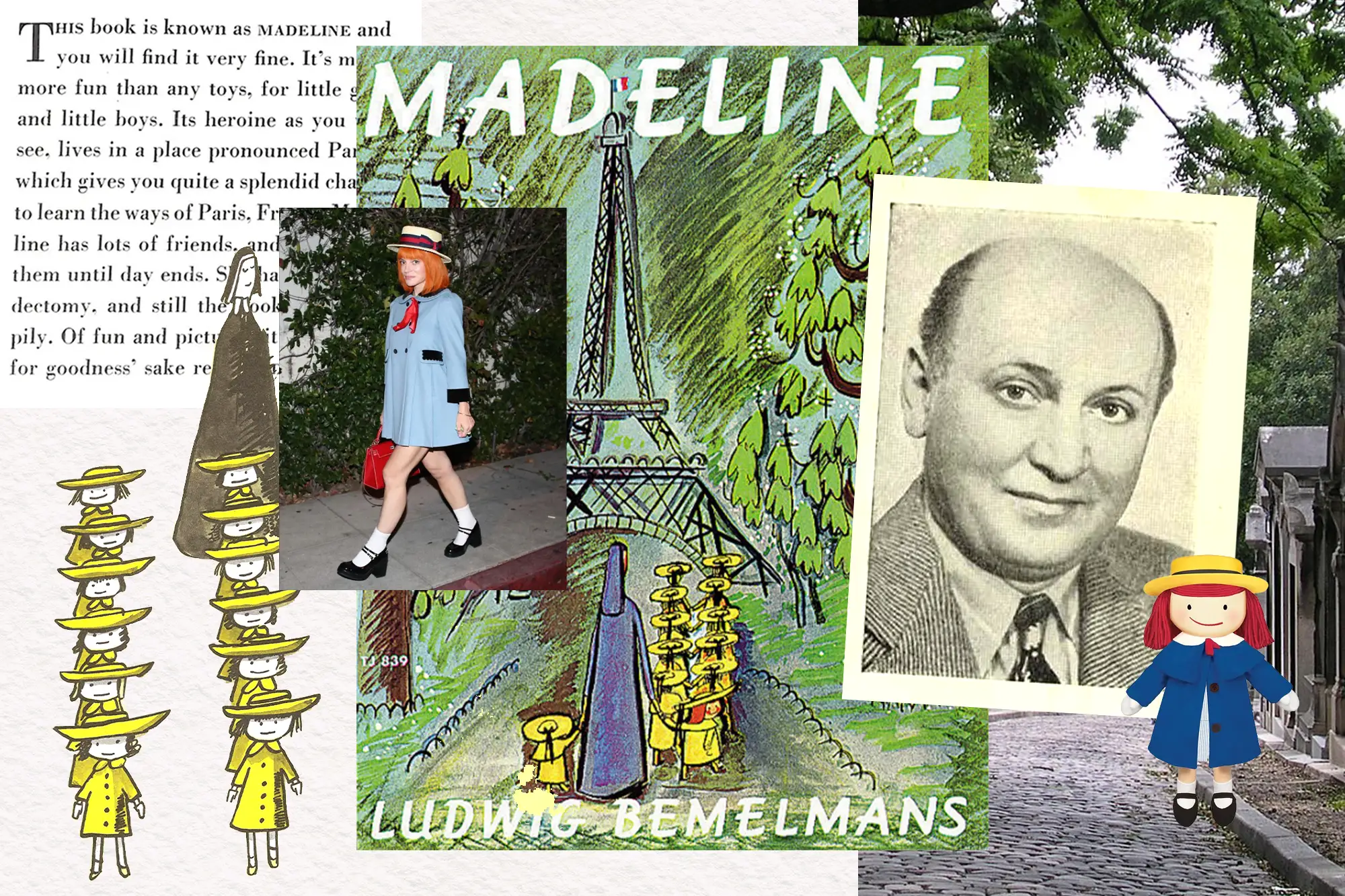

For many of us, this short rhyme was our introduction to a world equal parts quaint and captivating, a paintbrush Paris explored by the brave and curious Madeline. This little girl who confronted the mundane miracles and disproportionate terrors of childhood head-on captured the hearts and imaginations of so many of us, even if we misunderstood her story slightly.

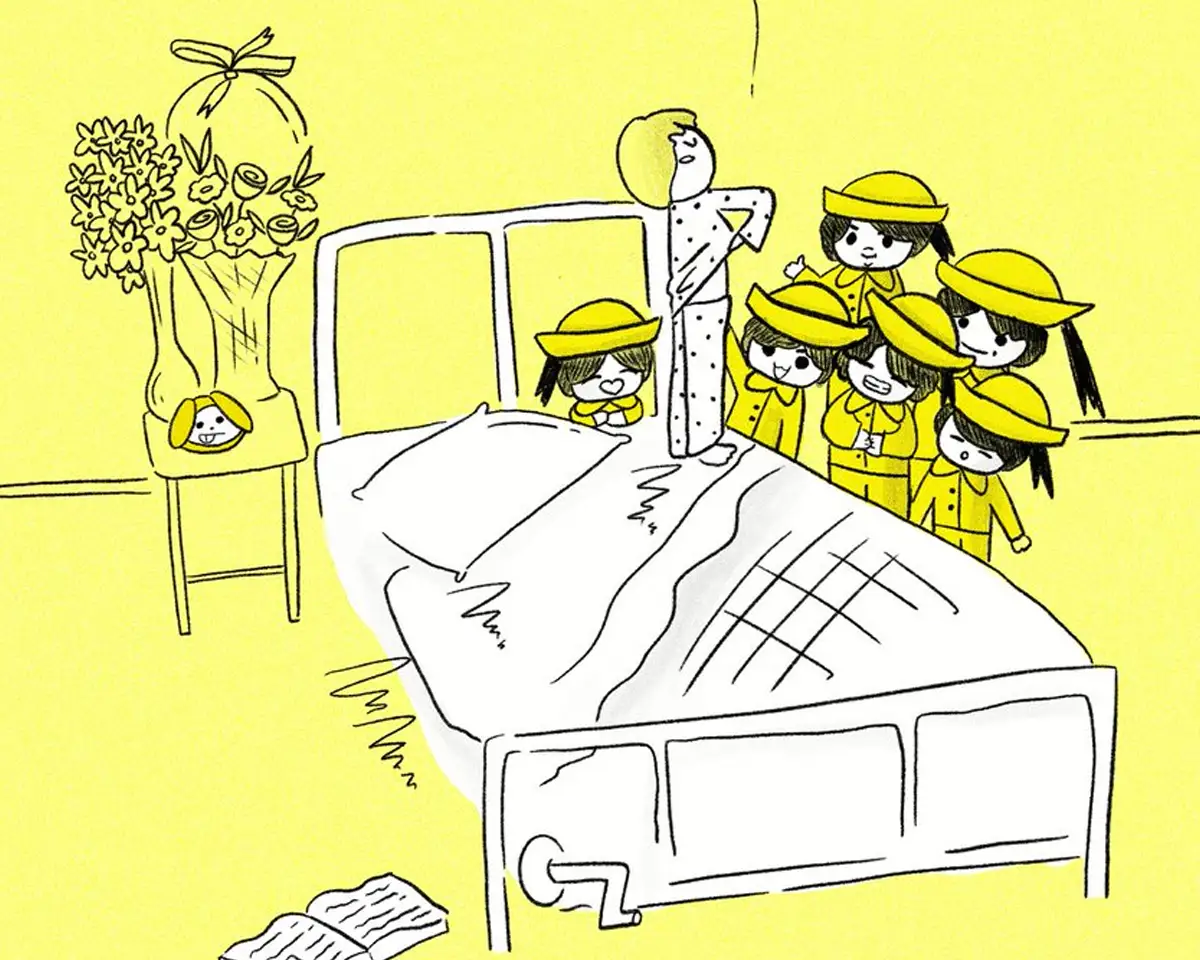

We can’t be the only ones who thought the old house in Paris was an orphanage, Madeline a French child, and Miss Clavel, a nun. This is a common misconception, but eagle-eyed readers will remember that in the original book when Madeline was in the hospital recovering from having her appendix removed, she receives a doll house from Papa, proving she is not an orphan.

Those who followed the series will also know that the rest of the books are predominantly set in America, where Madeline lives when she is not attending a French boarding school. Not only that, but apparently Miss Cleval’s outfit is not one of a nun, but a nurse.

If you’re shocked and mildly horrified, we understand, although who can blame us when the majority of beloved children's protagonists, from Harry Potter to Anne Shirley, have deceased parents?

But if you think that’s the craziest thing about the Madeline stories, wait until you hear about the life of its author and illustrator, Ludwig Bemelmans.

Bemelmans, like his protagonist, was not French. He was born in 1898 in Austria, in a region that is now Northern Italy. His father was a hotelier named Lampert, and a terrible philanderer.

Lampert left the growing family after impregnating Bemelmans’ mother Franciska as well as the governess the couple had hired to take care of their unborn child! The governess committed suicide not long after, leaving the 24-year-old Franciska alone to raise her child.

The young mother did her best to raise her son on her own, and it was Franciska’s stories of her childhood boarding school that would go on to inform Madeline’s. Yet her rambunctious son was a troublemaker, and so at 16, he was sent to go work for his uncle, who like his father was a Hotelier.

This is where things take an even darker turn. At his uncle’s hotel, Bemelmans was subject to the wrath of an abusive headwaiter, who made the boy’s life miserable.

“The headwaiter at that hotel was a really vicious man, and I was completely in his charge,” Bemelmans said of the experience. “He wanted to beat me with a heavy leather whip, and I told him that if he hit me I would shoot him. He hit me, and I shot him in the abdomen.”

The headwaiter survived, and the police told Bemelmans he either had to go to reform school or leave for America, he chose the latter.

Sixteen and alone in the United States, Bemelmans originally planned to meet his father in New York, but Lampert, in typical fashion, forgot to show up for his son. Bemelmans arrived on Christmas Eve of 1914 and spent the night alone on Ellis Island.

From that point on he began working in hotels, as well as serving in World War 1. As he moved up the ranks in the world of hospitality he began painting and decided to become an artist. He met his wife Madeleine (he removed the second e for the fictional character to make it easier to rhyme) and published his first children’s book Hansi with Viking Press in 1934. He and Madeleine had a daughter, who he cites as being an inspiration for the iconic character along with his wife and mother.

It was while vacationing in the South of France with his family that Bemelmans got the inspiration for the classic book. He had gone out one morning to get fresh fish from the seaside and while biking back was hit by a car! In the hospital recovering, he met a little girl recovering from an appendectomy.

“In the room across the hall was a little girl who had had an appendix operation, and, standing up in the bed, with great pride she showed her scar to me. Over my bed was the crack in the ceiling that ‘had the habit of sometimes looking like a rabbit.’ It all began to arrange itself. After I got back to Paris I started to paint the scenery for the book.” The first Madeline book was published in 1939.

Bemelmans had never intended to be a writer, but an artist, and so Madeline, with its sparse words and evocative scenes, was a perfect avenue for his illustrations.

“The text allows me the most varied illustration: there is the use of flowers, of all of Paris, and such varied detail as the cemetery and Pere la Chaise and the restaurant of the Deux Magots. All this was up there waiting to be used, but as yet Madeline herself hovered above as an unborn spirit.”

Today, Madeline has become a family business, with new books being released by Bemelmans' grandson. While Bemelmans always said Madeline was an amalgamation of all the important women in his life: his mother, his wife, and his daughter, his grandson feels differently, saying that ultimately Madeline is a reflection of Bemelmans himself.

“He was the littlest kid in class," his grandson says. "He always felt like an outsider. He was getting into trouble. So I think it was very autobiographical.”

That little outsider, despite a childhood that was deeply troubled, created one of the most precocious, beloved childhood characters of all time, orphan or not.

For more information check out:

Lepper, Amanda, “The Story Behind the Story of Madeline” Going on a Book Hunt, March 10 2014.

NPR Staff, “At 75 She's Doing Fine; Kids Still Love Their 'Madeline'” NPR, October 11 2013.