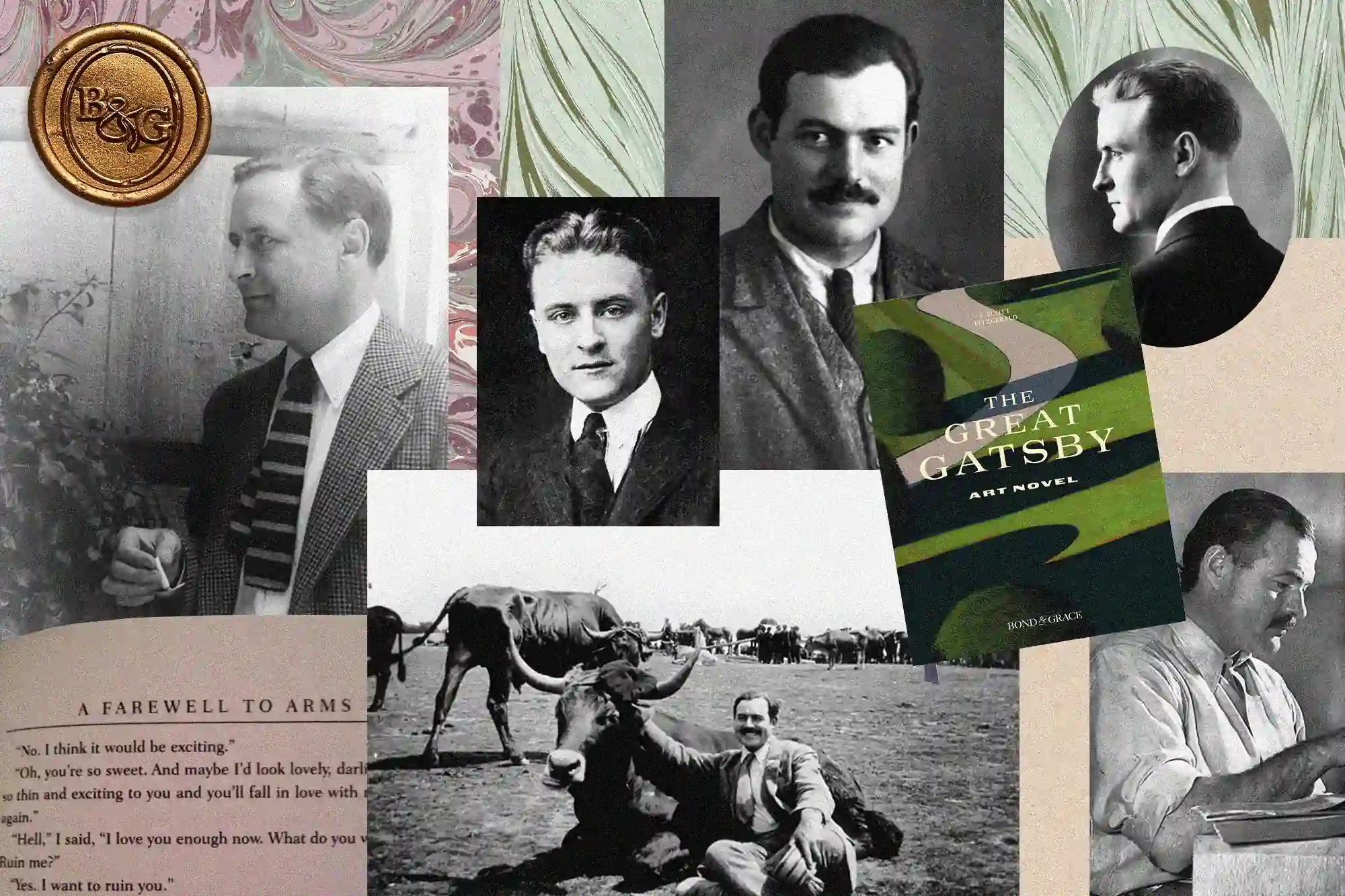

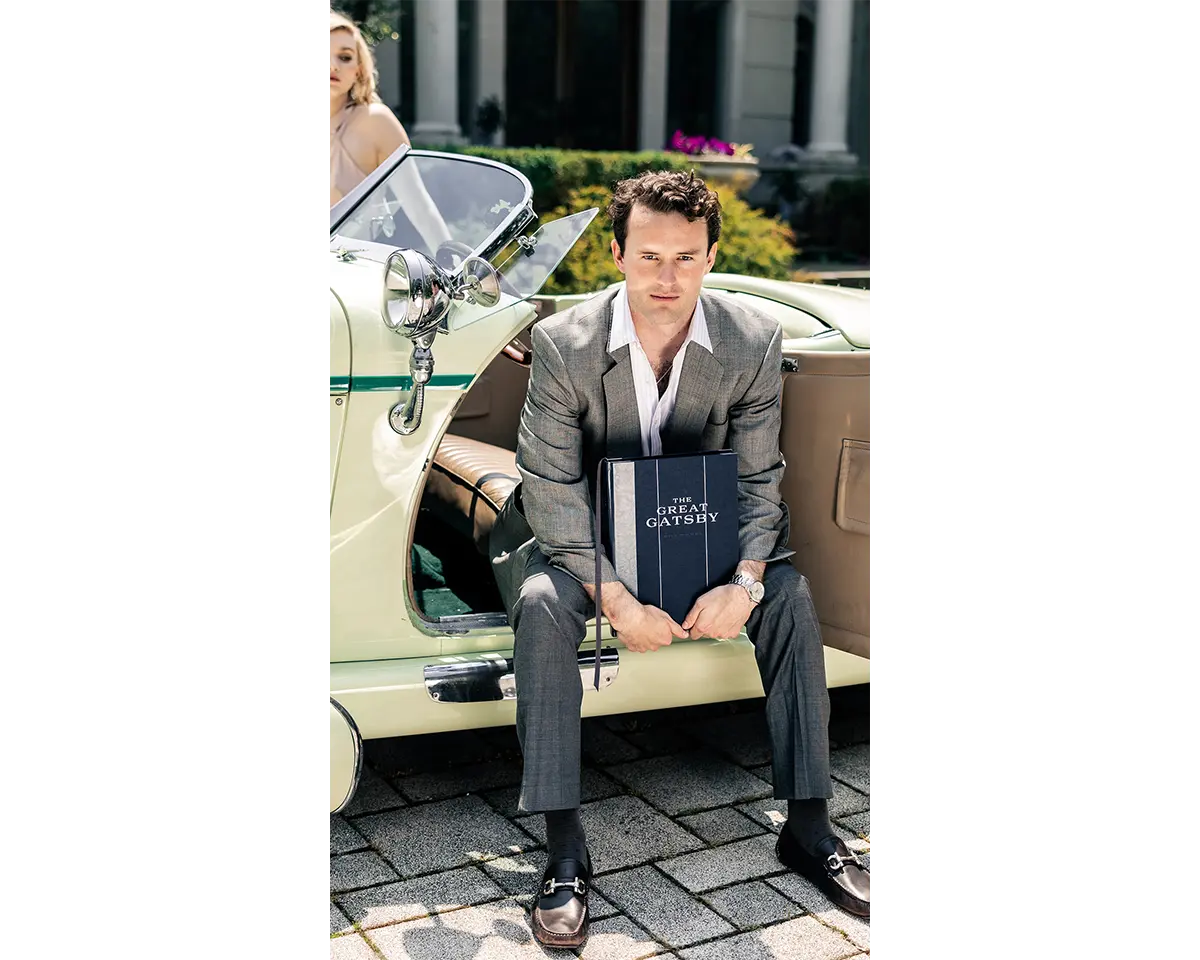

In 1896, writer John William DeForest coined the idea of The Great American Novel, a book that would, in his words, accomplish “the task of painting the American soul.” And while the title has many contenders, today, there is one book that is widely considered the Great American Novel: F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby.

DeForest identified “the American soul” as the crux of the Great American Novel, but perhaps even more significant is the distant dream that motivates American souls, that elusive idea upon which our nation was founded—the American Dream. Gatsby is, at its core, a novel about dreamers, pursuing distinctly American dreams. The infamous symbol of the green light shining from across the Long Island Sound has become a stand-in for all our national hopes and aspirations. But what does the novel actually say about those dreams, and whether they are worth pursuing?

Many may remember Jay Gatsby and his pursuit of wealth and status—all in the hopes of winning back Daisy—as being the most quintessential of American success stories. Gatsby, born to “shiftless and unsuccessful farm people,” comes from nothing and rises to an almost mythic status. With his giant mansion, glossy yellow car, and “Old Sport” catch phrase, he appears to have accomplished all he sought out to; he even gets Daisy back, if only for a brief time. But then Daisy returns to her terrible husband, Gatsby is murdered by George Wilson, and all our dreams seem dead in the water. The novel’s close leaves readers wondering what Fitzgerald is actually saying about the American Dream, and if it’s as dead as Jay Gatsby himself.

Fitzgerald’s thoughts on the American Dream are complex and subtle, but the truth of them are there for those who read closely.

Gay, Exciting Things

To understand what Fitzgerald is arguing about the American Dream, we must first clarify what exactly that dream is. Many think Gatsby’s dream is simply to become rich and successful and win back Daisy, which is true. But there is a deeper dream that the money, the success, and the girl are all in service of. For Gatsby, his true dream is a romantic and charmed view of the world that can only be obtained from inherited wealth. This is the thing that Daisy provides for him, the thing he cannot simply go out and buy himself.

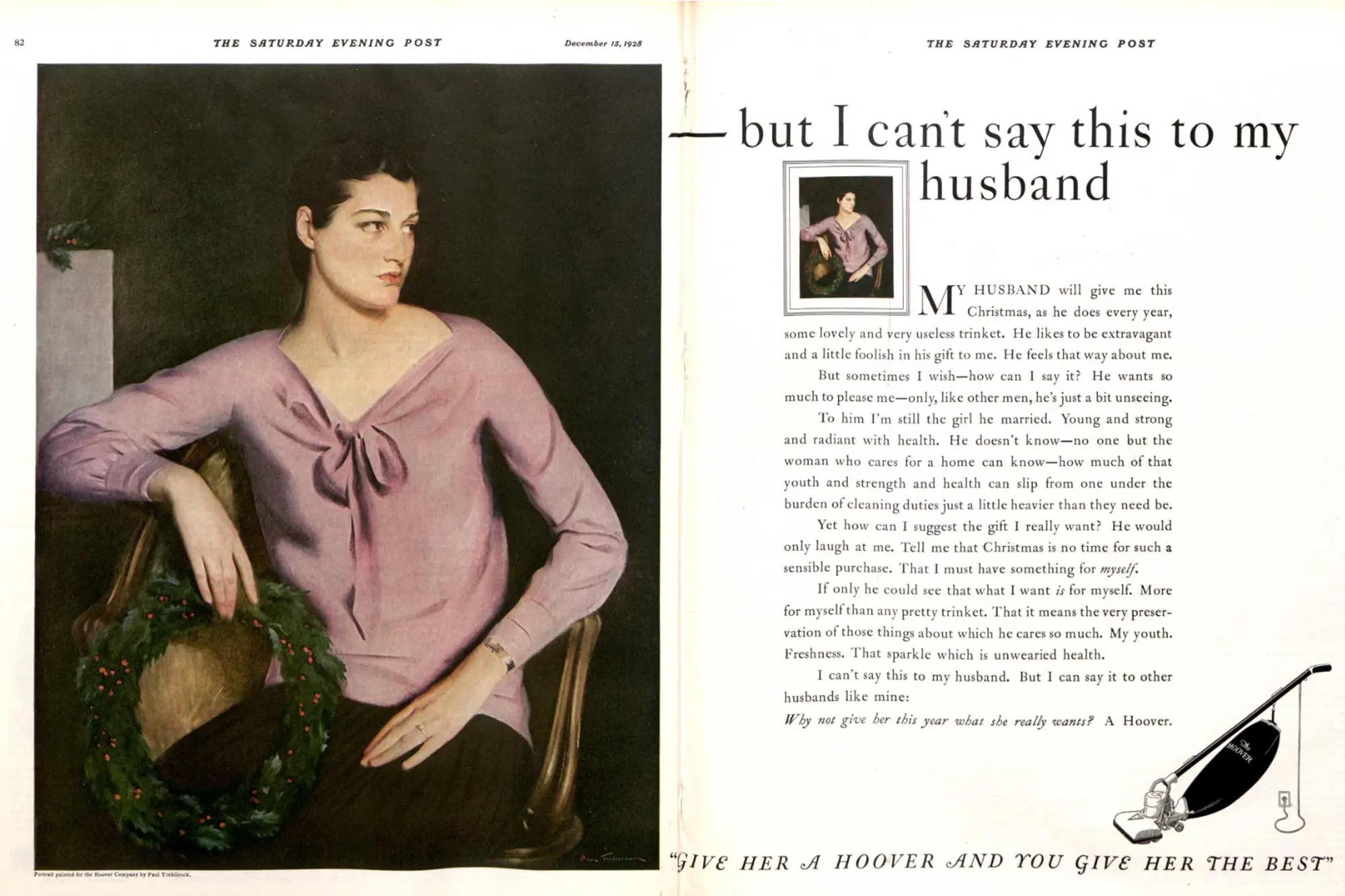

In Chapter 2, Fitzgerald says that Daisy’s voice—the epicenter of her power and magnetism—promises “that she had done gay, exciting things just a while since and that there were gay, exciting things hovering in the next hour.”

In Chapter 8, as Gatsby recalls his original courtship of Daisy, Nick tells us, “Her porch was bright with the bought luxury of star-shine; the wicker of the settee squeaked fashionably as she turned toward him and he kissed her curious and lovely mouth. She had caught a cold and it made her voice huskier and more charming than ever, and Gatsby was overwhelmingly aware of the youth and mystery that wealth imprisons and preserves, of the freshness of many clothes, and of Daisy, gleaming like silver, safe and proud above the hot struggles of the poor.”

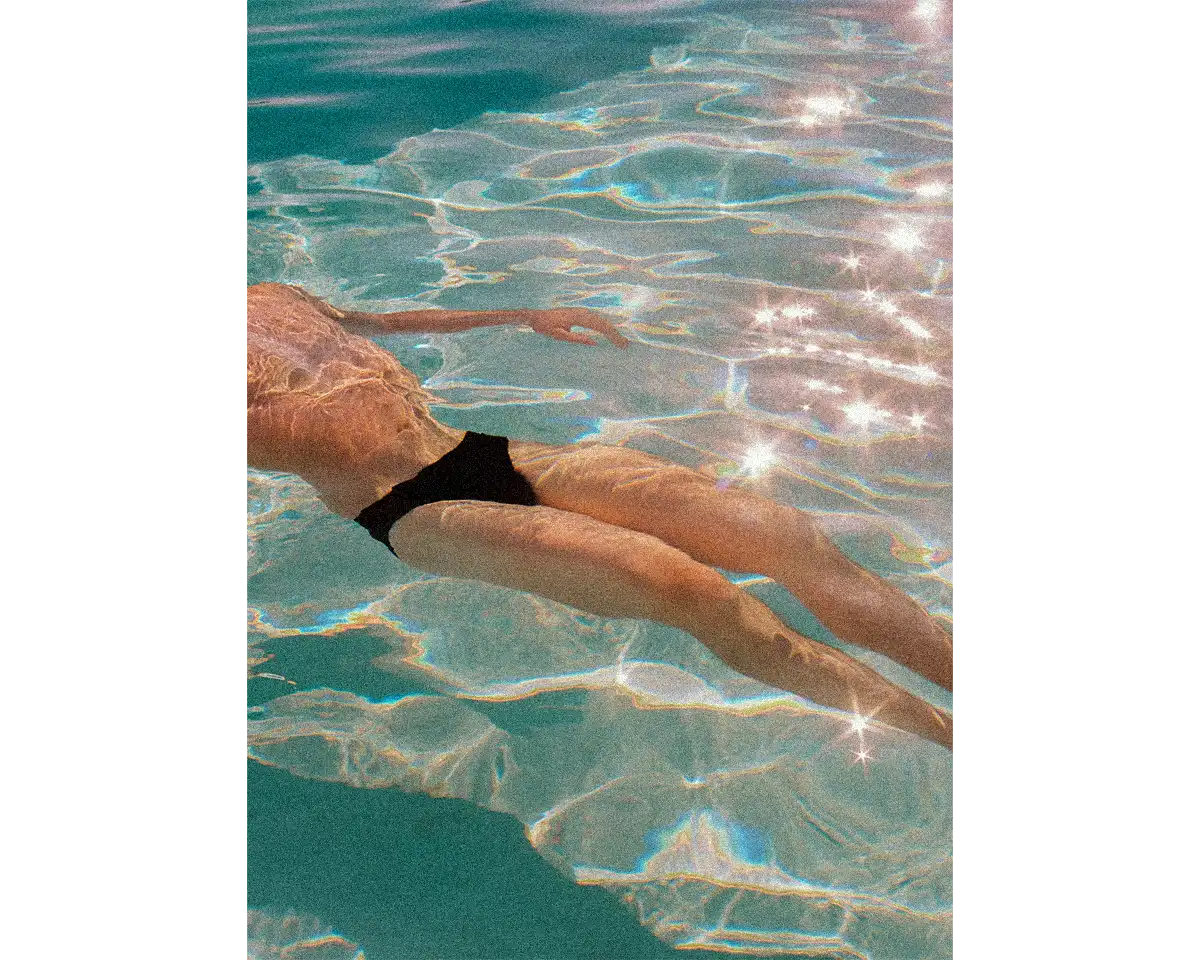

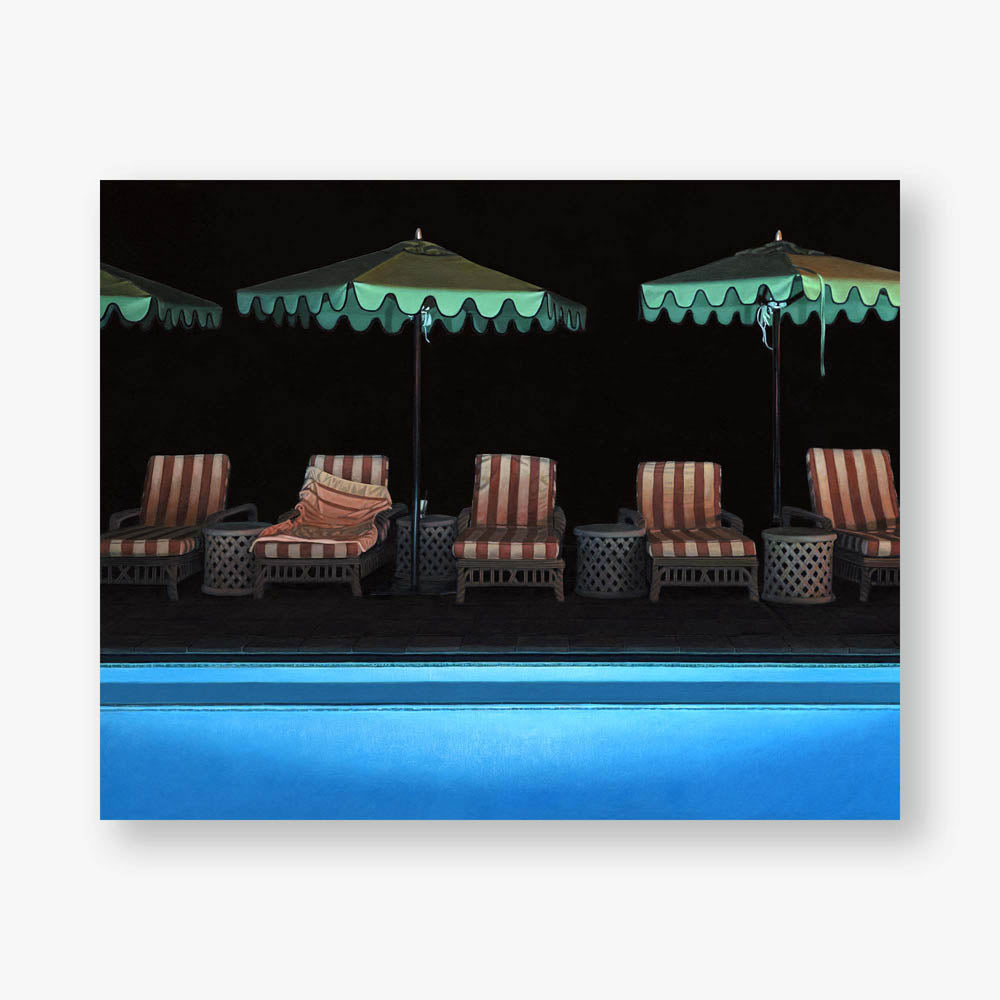

This romantic and radiant view of the world that Gatsby pursues is also the one thing he can never fully obtain. He cannot buy it or construct it; it must be inherited. In the moments before Gatsby is murdered, he sees that dream stripped away, reduced to a world of raw matter: “He must have felt that he had lost the old warm world, paid a high price for living too long with a single dream. He must have looked up at an unfamiliar sky through frightening leaves and shivered as he found what a grotesque thing a rose is and how raw the sunlight was upon the scarcely created grass. A new world, material without being real.”

If we, like Gatsby, make the pursuit of the magic and mystery of money our American Dream, then Fitzgerald makes clear that we will fail or die trying. But there is another, perhaps nobler dream, that might be within reach.

A Fresh Green Breast

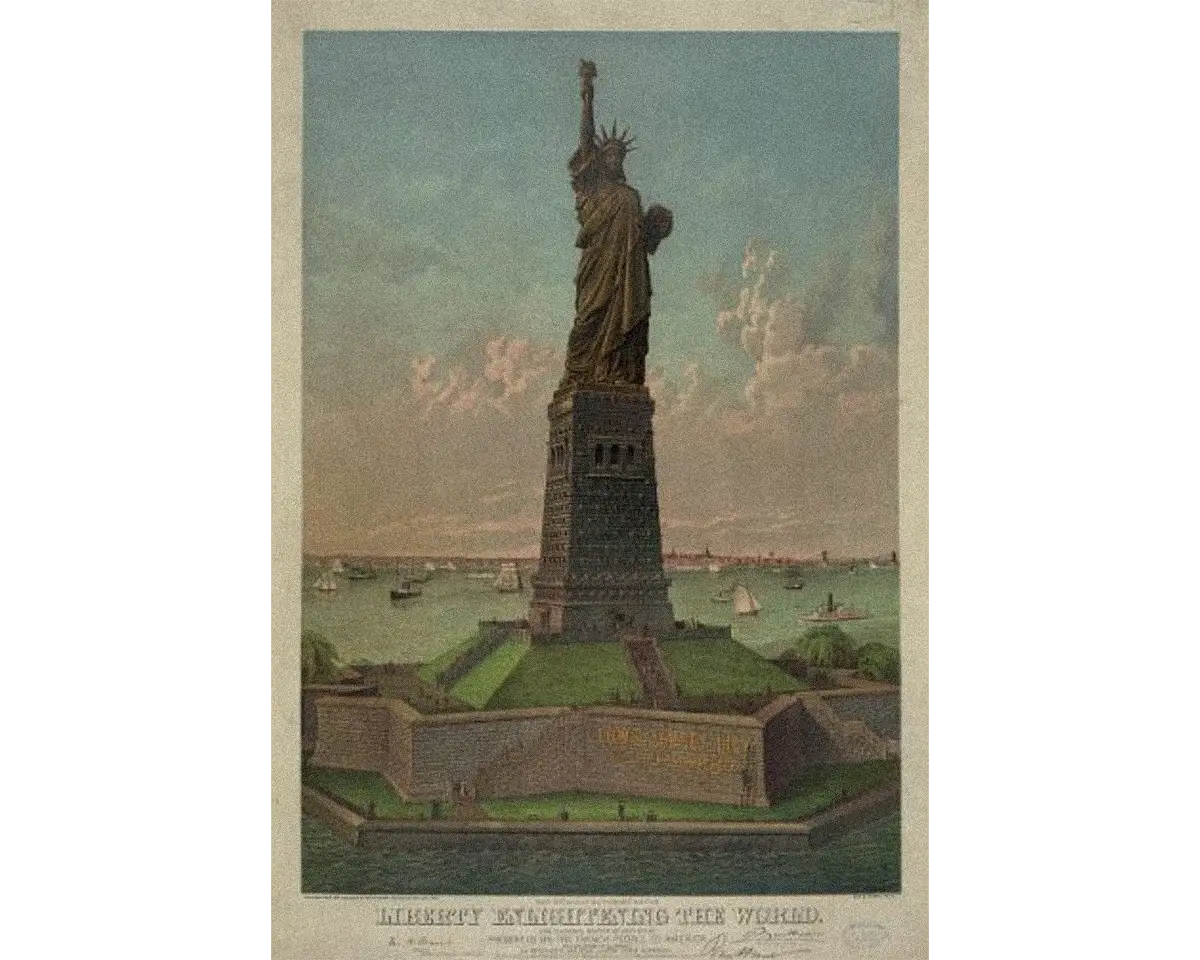

In the novel’s closing passage, as Nick reflects on how Gatsby’s death has ruined New York for him, he suddenly widens his scope. He goes from talking about the man, the mansion, to the entirety of America itself: both past, present, and future. He says, “And as the moon rose higher the inessential houses began to melt away until gradually I became aware of the old island here that flowered once for Dutch sailors’ eyes – a fresh, green breast of the new world. Its vanished trees, the trees that had made way for Gatsby’s house, had once pandered in whispers to the last and greatest of all human dreams; for a transitory enchanted moment man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent, compelled into an aesthetic contemplation he neither understood nor desired, face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder.”

What Nick—and Fitzgerald by extension, identifies here—is another, truer dream. A national dream. Nick travels back in time to what the Dutch sailors must have seen the first time they spotted New York, and what it must have implied about the vast land that stood before them. This is, I would argue, the true American dream. It is the hope of America, a place of freedom and meritocracy, a place where anyone can reinvent themselves, a place where dreams come true.

Borne Back

Gatsby’s glittering dream, the dream that accompanied Daisy, died with him in the pool, but to this second dream, Fitzgerald gives a different fate.

We know that what those Dutch sailors hoped for did not come true. That American dream was marred by the violence of colonization the moment the boat touched ground. This nation of lofty ideals was constructed through genocide and enslavement. Fitzgerald knew this too, calling the sailor’s view from sea “the last time in history” anyone witnessed “something commensurate to his capacity for wonder.”

However, that doesn’t mean it is dead, exactly. Perhaps the better word would be past. It was past the moment the sailors reached land. The ideal of America was always a vision, made distant by the very efforts to bring it closer. This is what Fitzgerald reveals in the novel’s infamous closing passage. “And as I sat there brooding on the old, unknown world, I thought of Gatsby’s wonder when he first picked out the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock. He had come a long way to this blue lawn, and his dream must have seemed so close that he could hardly fail to grasp it. He did not know that it was already behind him.”

Still, there is an important distinction between dead and passed; Fitzgerald makes that clear in the final sentences of the novel. “Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter – tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms further . . . And one fine morning— So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

What The Great Gatsby says about the American Dream is that it is already behind us. It is an ideal that only existed at the moment of its dreaming. But that doesn’t mean we should stop reaching for it. It may be futile and it may be painful, but we will, nay should, continue to hope for it and strive to make it a reality. We may never quite reach it, but there is something worthwhile in the journey, in the boats beating against the current. The American Dream may be perpetually out of reach, but if that sentiment doesn’t capture the American soul, I don’t know what does. The Great American Novel indeed.

.webp)