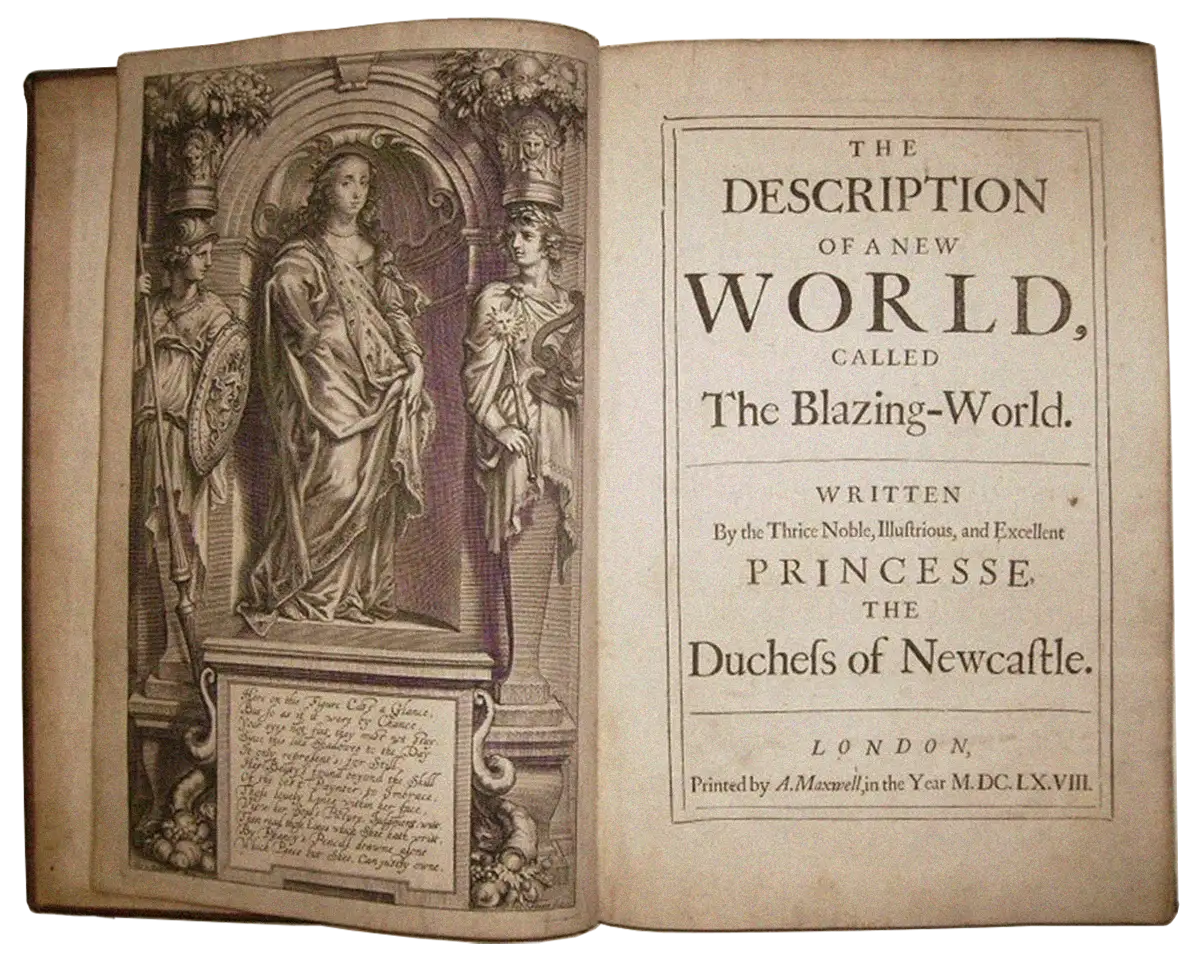

Margaret Cavendish’s The Blazing World (1666) centers on new beginnings through a fictionalized version of herself called Margaret the First who enters an alternate world and must transform both herself and the society she comes to rule. Cavendish later writes a secondary character from another world—named and identifiable as another version of the author—who meets and converses with the Empress. These encounters take place across distinct realms: Cavendish’s own world and the Blazing World.

The year 2026 marks 360 years since the original publication of Cavendish’s proto–science fiction novel. Coincidentally, this month also marks the fifth anniversary of Carlson Young’s directorial debut of The Blazing World, which premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in January 2021. While Cavendish developed a utopia, Young constructed a darker, fantasy-horror dystopia. Despite altering the original narrative, Cavendish's philosophy shines through, illustrating that “if nature be infinite, there must also be infinite worlds,” as the English philosopher and Duchess wrote in her 1666 (revised 1668) work Observations upon Experimental Philosophy. But while Young’s adaptation nods to Cavendish’s original story, the two works together speak to a lineage of women using speculative worlds to explore autonomy, revealing how the multiverse has evolved since its proto-feminist origins.

Cavendish created The Blazing World as a companion piece to Observations upon Experimental Philosophy in order to expand upon its natural-philosophical ideas through fiction. She imagined an alternative world where a woman could reshape science and society, using the story as a space to explore her theories and politics in a more imaginative mode. In this unrestricted world, she gave herself a fictional escape to explore these ideas freely.

As the story goes, a storm-driven wind carries Margaret the First to the Blazing World by way of the North Pole, an alternate realm inhabited by hybrid human-animal beings. As Margaret travels through the world, she learns from these creatures, teaches them her knowledge, and together they work to better the land. Upon meeting her, the Emperor of the Blazing World falls in love with her and marries her, after which she becomes Empress. Cavendish originated what modern audiences might associate with multiverses through a narrative which encounters alternate versions of the self and a fantastical interdimensional war. Working with alternate versions of herself, she proves herself a leader. The text pointedly emphasises Cavendish’s advocacy for female education and friendship.

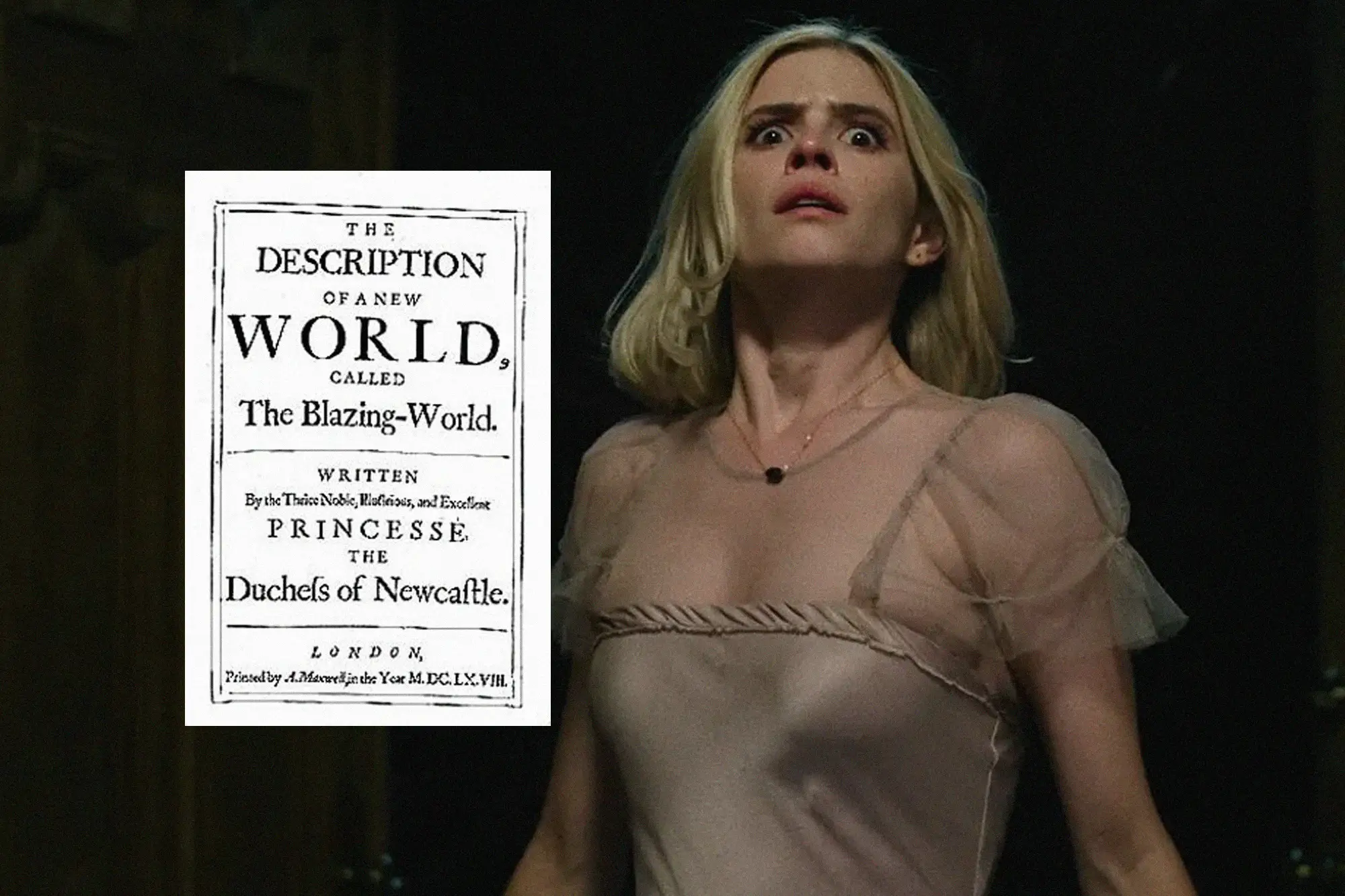

Conversely, Carlson Young’s 2021 film The Blazing World blends the actress and director’s engagement with Cavendish’s philosophy with her own interest in childhood trauma and how it is processed through development. A Bluebeard reference—where a forbidden door reveals irreparable truth—shapes Margaret’s arc: she “sees the truth, and after that the key won’t stop bleeding.” The film’s visual style cites Dario Argento’s 1970s horror films, Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, and the surrealism of David Lynch and Guillermo del Toro. Young’s pastiche creates a multifaceted world of macabre wonder and stands as one of the few contemporary works by a woman to directly reference Cavendish’s original novel, alongside Siri Hustvedt’s novel The Blazing World (2014).

The film integrates whimsy and violence from the outset, beginning with a flashback of twins Margaret and Elizabeth Winter (Josie and Lillie Fink) catching fireflies. Margaret becomes distracted by her parents arguing in the kitchen and doesn’t realize that Elizabeth is drowning in their pool while trying to catch more fireflies. Opposite her, a portal opens with Lained (Udo Kier) beckoning her—though unlike the novel, she does not travel through it yet.

The story then shifts to Margaret (now played by Young), a college student fascinated by spirituality and alternate worlds, who corners a talk show host to ask whether one can truly become trapped in another dimension. It is here that Cavendish’s philosophy comes into focus. Her return home from college up North echoes Cavendish’s own northern passage into the Blazing World. Back in her childhood home, unease grows as Margaret reunites with her ex-boyfriend Blake and experiments with acid before returning to the house. When she does, the front doors are locked, and a second portal opens, drawing her after Lained and Elizabeth. She enters an overgrown version of her garden, where she meets Lained and learns that her sister is still alive but trapped by four demons, each guarding a key she must retrieve before the candle burns out. While Lained gives up his key, the remaining demons appear as distorted versions of her parents (Dermot Mulroney and Vinessa Shaw) who are far less willing to let theirs go.

While the novel states that the Blazing World is one of Cavendish’s “fancies,” the film continually invites the audience to question whether Margaret’s experiences are real, punctuated by brief snapshots of Margaret in the bath with Lained forcing her underwater, as a portrait of Cavendish herself watches over her. Back in the Blazing World, Margaret runs out of time and becomes trapped in a room of mirrors and neon lights. In the reflections, she sees herself on fire, referencing the burning fire-stone in the novel. While Cavendish uses it to make her enemies submit to her authority, Young employs it to emphasize Margaret’s despair. With escape eluding Margaret, she attempts to end her life, but is stopped by her sister’s hand, realizing she has been with her throughout her life, watching over her, just as Cavendish's portrait. This moment draws on philosophical concepts of transcending corporeality and recalls Kate Lilley’s analysis of Cavendish’s original text, asserting that women’s souls can communicate through platonic love across worlds and bodies.

Lained, angered by Margaret’s desire to leave rather than remain with a version of Elizabeth who is not truly her sister, belittles her. Instead of yielding to him, Margaret responds, “mistake the darkness for fear no more,” a line reminiscent of John 1:5: “and the light shineth in the darkness; and the darkness comprehended it not.” This moment feels like a fitting convergence of Cavendish’s and Young’s Christian upbringings, suggesting the possibility of finding God even in the darkest places. Swarmed by fireflies, Lained is defeated, and water crashes through the door, pulling Margaret back into her bath. The ending raises the question of whether her journey through this pseudo-Wonderland was real or a manifestation of her internal struggle upon returning home. In the final scene, Margaret brings her parents into the garden to catch fireflies, creating a cyclical narrative and allowing the Winter family to associate the act with a gentler memory. This conclusion echoes the novel’s themes of leaving the past behind in pursuit of new beginnings and shifts the film’s tone toward the hopeful, utopian spirit of Cavendish’s work— given the chance, could Young’s protagonist make extraordinary achievements just like Cavendish’s?

Each version of The Blazing World marks a pivotal shift in its creator’s career: Cavendish’s debut novel and Young’s directorial and screenwriting debut. Both are richly detailed works of art, though neither escaped criticism.

Cavendish’s peers nicknamed her “Mad Madge” in an attempt to discredit her. Samuel Pepys described her as “mad, conceited and ridiculous,” and after her visit to the Royal Society, remarked, “I do not like her at all, nor did I hear her say anything that was worth hearing.” Though The Blazing World is not the most accessible text, it remains a remarkable achievement for a seventeenth-century woman—particularly one who insisted on publishing her name and portrait alongside her work. Her theories persist across modern philosophy, mathematics, and science, most notably in science fiction’s enduring fascination with the multiverse.

Young’s film similarly garnered mixed reviews, with some critics suggesting that despite its imagination, the narrative struggled against “stylistic self-indulgence.” Bloody Disgusting’s Megan Navarro remarked that one could hardly grow bored by a “whimsical horror-fairy tale on acid,” while Variety’s Guy Lodge wrote, “it’s Carlson Young’s blazing world, and we’re barely invited into it.” While these critiques are understandable, I disagree, finding the film beautifully and cohesively constructed. Notably, the opening title card reads “a Carlson Young film,” an uncommon choice for a debut and one that recalls Cavendish’s insistence on publishing her portrait and name alongside her book.

Though separated by over three and a half centuries, both versions of The Blazing World continue to illustrate the importance of female autonomy. On this milestone anniversary, the multiverse Cavendish imagined continues to expand through women’s voices, evolving from utopian ideals into modern dystopian explorations. Both Margaret Cavendish and Carlson Young ultimately explore what it means to metamorphose into a newer, healed version of the self.