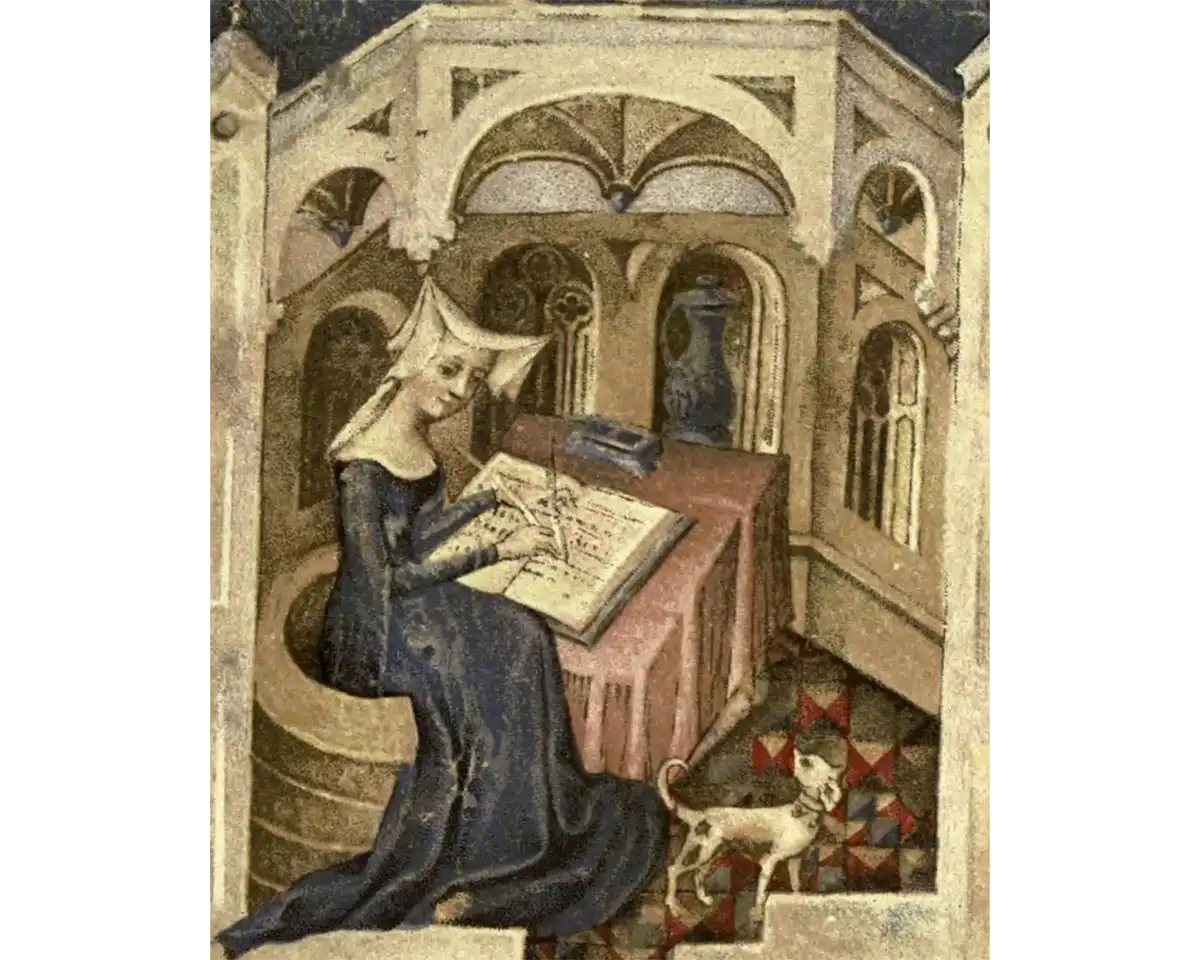

When the widowed French writer Christine de Pizan sat down to write a book defending the intellectual capabilities of women in 1404, she had little choice but to frame it as fiction.

As one of the first professional female writers in Europe working during the late medieval period, de Pizan knew her case against misogyny would carry more weight if structured as allegory —emulating the structure of allegorical texts by Dante, Boethius, and other respected male authors—than as an argumentative essay. Titled The Book of the City of Ladies (1405), de Pizan constructed a symbolic city where strong women from history and mythology engage in dialogue, defend their opinions, and mentor each other, fostering the community, connection, and intellectual solidarity that had long been denied to them in medieval society.

“Not all men (and especially the wisest),” wrote de Pizan, “share the opinion that it is bad for women to be educated. But it is very true that many foolish men have claimed this because it displeased them that women knew more than they did.” Indeed, in the two centuries after de Pizan put pen to paper, two major cultural shifts would support European women’s ability to learn and convene: the printing press widened access to literature, and the Renaissance ushered in newfound interest in humanism, reason, and intellectual thought, offering upper class women an entryway into educational circles and scholarly conversations.

Suddenly, knowing what to say, and how to say it, carried cultural cachet for men, especially in formal environments such as the high court. As society placed increasing emphasis on humanist thought and individual curiosity, it was only natural for aristocratic women to want their part in such stimulating conversations. High society women began to pursue education in informal settings, through private tutors or in their home libraries, opening their minds to the ideals of intellectual refinement. Pedigree, in other words, shifted during the Renaissance era; no longer solely about heritage, men—and increasingly women—began to see knowledge and cultural literacy as a means of social capital.

The Blue Room: Catherine de Vivonne and the Birth of the Salon (1620–1648)

And so, women of the Renaissance-era did what they always do best—circumnavigate the challenges posed by the patriarchy, which in this case included their lack of access to formal education. Salon-style conversations emerged among the wealthy elite in Italy as early as the 16th century, as women took it upon themselves to organize the first book clubs, or learning circles, where it was they—not their husbands or brothers—who called the shots.

One such memorable salon from the 17th century was the “Chambre Bleue” (or Blue Room), organized by the French noblewoman Catherine de Vivonne, also known as the Marquise de Rambouillet, who hosted intellectual circles in the small space next to her daybed. Attendees were not the bohemian kind but rather scholars, writers, and noble philosophers of great renown, who I imagine showing up in elaborate coats and gowns so oversized and embellished that they can hardly fit in Catherine’s drawing room.

Hand selected by Catherine, participants embodied what came to be known as “honnêteté,” or effortlessness, grace, and aristocratic virtue. What the salon called “précieux” became an identity marker for the group; being invited and contributing meaningfully to literary and philosophical discussions was a signifier of social capital. “High society women,” writes Benedetta Craveri in The Age of Conversation, “took it upon themselves to educate the men.”

And so, the art of female-led conversation was born, paving the way for intellectual discussions, the seeds of early feminism, and eventually, the rise of formal female education across Europe.

A Hostess Unafraid to Say “That’s enough:” Madame Geoffrin’s Salons (1740s–1760s)

A century later, another French noblewoman and intellectual by the name of Madame Geoffrin also made a name for herself as a salonnière, capitalizing on the growing cultural shift toward private, domestic residences and away from the increasingly tiresome scene at the French court. Geoffrin had been introduced to the unorthodox salon gatherings of Madame de Tencin as a child, and, inspired by them, went on to establish her own salon, becoming a key cultural figure of the Enlightenment.

Garnering the attention of influential foreigners and peaking during the 1740s–1760s, Madame Geoffrin’s salons were orderly, reputable, and alive with conversation running the gamut of topics from literature to music to current events. Her salon’s success could be attributed to four factors: she had a knack for hosting effortlessly while instituting formal structure—two weekly dinners, one for philosophers, and one for artists; she elevated the salon beyond a leisure activity into a dignified forum for discussion; though she was not a writer herself, she was opinioned and direct, able to hold her ground in a room of Enlightenment thinkers; and lastly (and arguably the most strategic and essential of them all), she forbade religion and politics as topics of discussion. Poised and always ready to interject with a “Voilà qui est bien,” or “that’s enough,” she was a smart hostess indeed.

“Brilliant in Diamonds, Critical in Talk:” The Bluestockings Circle (1750s–1790s)

Out of the same cultural movement arose another influential women-led salon tradition in England: the Bluestockings Circle, which gathered in the homes of prominent London women such as Elizabeth Montagu and Elizabeth Vesey. Founded in the 1750s, these decidedly informal social gatherings evolved from casual literary discussions into a network of culturally engaged men and well off women who supported women’s education and heralded intellectual and artistic exchange across gender lines. Many of the women who attended were known for their letter writing, an early form of authorship for women and a powerful intellectual tool during an era when women were not formally educated. (Hostess Elizabeth Montagu supposedly wrote over 8,000 letters in her lifetime.)

Praising a woman's intellect over her appearance, the group’s name supposedly derives from an early gathering in which a botanist named Benjamin Stillingfleet wore the blue worsted stockings of working-class men, having forgotten to change into white silk. Yet the value of intellect didn’t seem to stop the Bluestockings’ hostesses from donning their diamonds—as the Welsh writer and Bluestocking leader Hester Thrale described Elizabeth Montagu in a letter, she was “brilliant in diamonds, solid in judgement, critical in talk.”

Female Intelligence as a Threat to Political Power: Madame de Staël (1804–1810)

By the time the French political theorist Madame de Staël entered the salon scene in the late 18th century, the demands had changed; in contrast to the restraint and refinement associated with earlier salons such as Madame de Rambouillet’s Chambre Bleue, de Staël was outspoken in her demand for visibility, authority and a political voice—and a frequent challenger to Napoleon’s rule. Intellect, for Madame de Staël, was a weapon; she wrote, “Intellect does not attain its full force unless it attacks power.” Exiled from France after refusing to conform, she transformed her estate at Coppet (a small town in Switzerland 10 miles from Geneva) into an intellectual refuge known as the “Coppet Group” where she influenced liberal thought across Europe, blending Enlightenment ideals with Romanticism.

Salons as Early Paths to Female Freedom

While formal education for women in Europe didn’t emerge fully until the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, salon-style conversations gave women an early forum to prove their worth, wit, and intellect, as they raised male eyebrows across the room with their ability to hold court in intellectual conversations. Even still, it would take generations of cultural, legal, and institutional reform—coupled with early feminist advocacy by the likes of Mary Wollstoncraft—before education would become accessible to working-class women, and even later, non-white women.

What we can and should take away from each of these early feminized spaces of power is that erudition carries cultural and social capital—then as it does today. The deeper we venture into books, the farther we explore in dialogue and thought, the harder it becomes for anyone to suppress our beliefs or our power. Five centuries after Christine de Pizan imagined a fictional world of women living freely and fostering their intellectual truths, Virginia Woolf famously put a lock and key around her thoughts, writing in 1929 in A Room of One’s Own, “there is no gate, no lock, no bolt that you can set upon the freedom of my mind.”

Recommended Reading

How the salons of Paris made social life an art, The New York Times

Women in the French Revolution: From the Salons to the Streets, Library of Congress Blogs