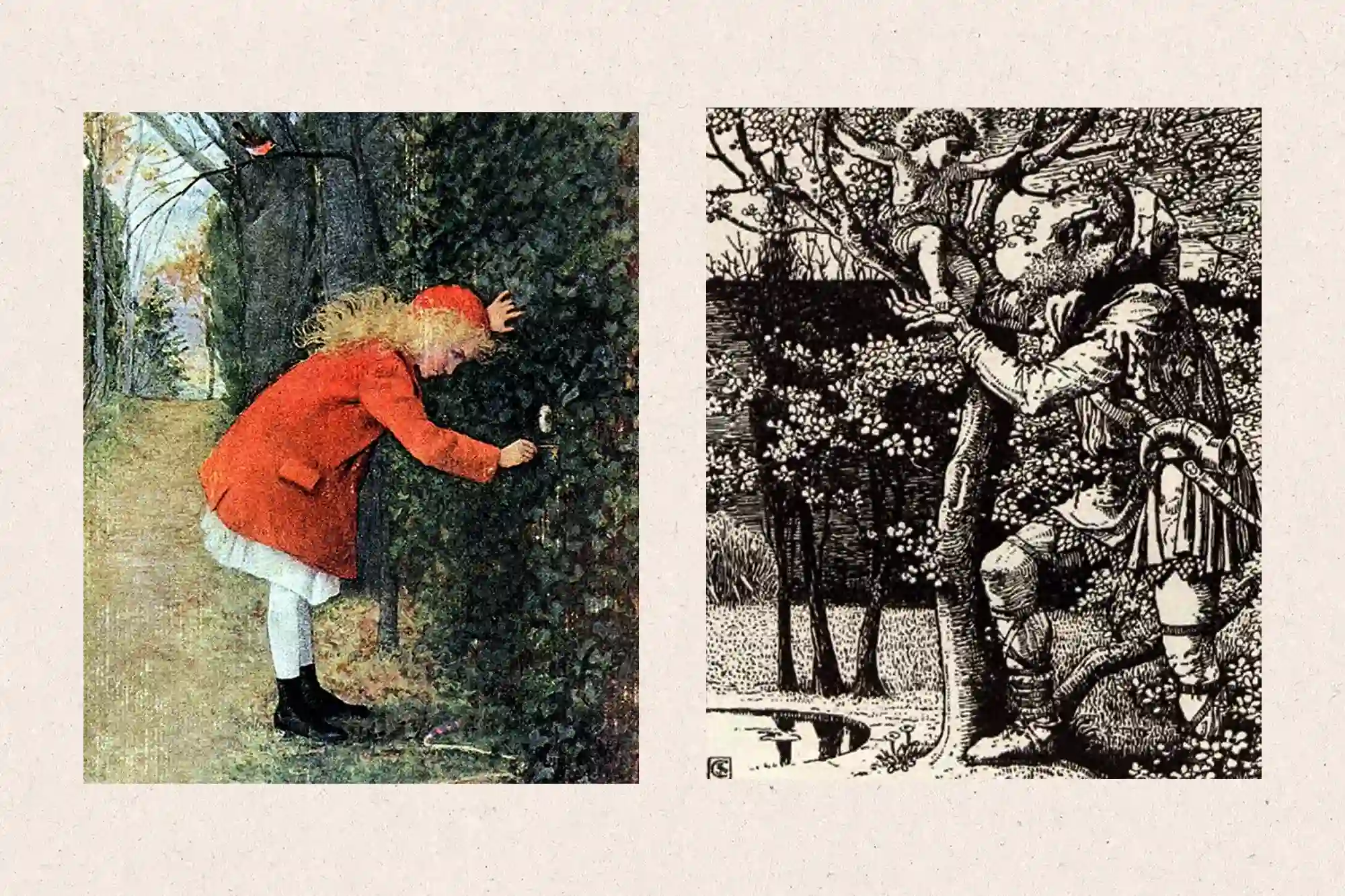

When I was a child, I was enthralled by fairy tales—including those by Hans Christian Anderson, the brothers Grimm, Andrew Lang, and Alexander Afanasyev. One that I loved dearly was Oscar Wilde’s The Selfish Giant.

Written in the classic manner of fairy tales about enclosed and forbidden gardens (as in “Beauty and the Beast”), the eponymous giant is furious that children have discovered, and delight in, his private garden. The giant banishes them, and—selfishly—builds a high wall around the garden to keep them out. Endless winter ensues, until the children surreptitiously return through a hole in the wall.

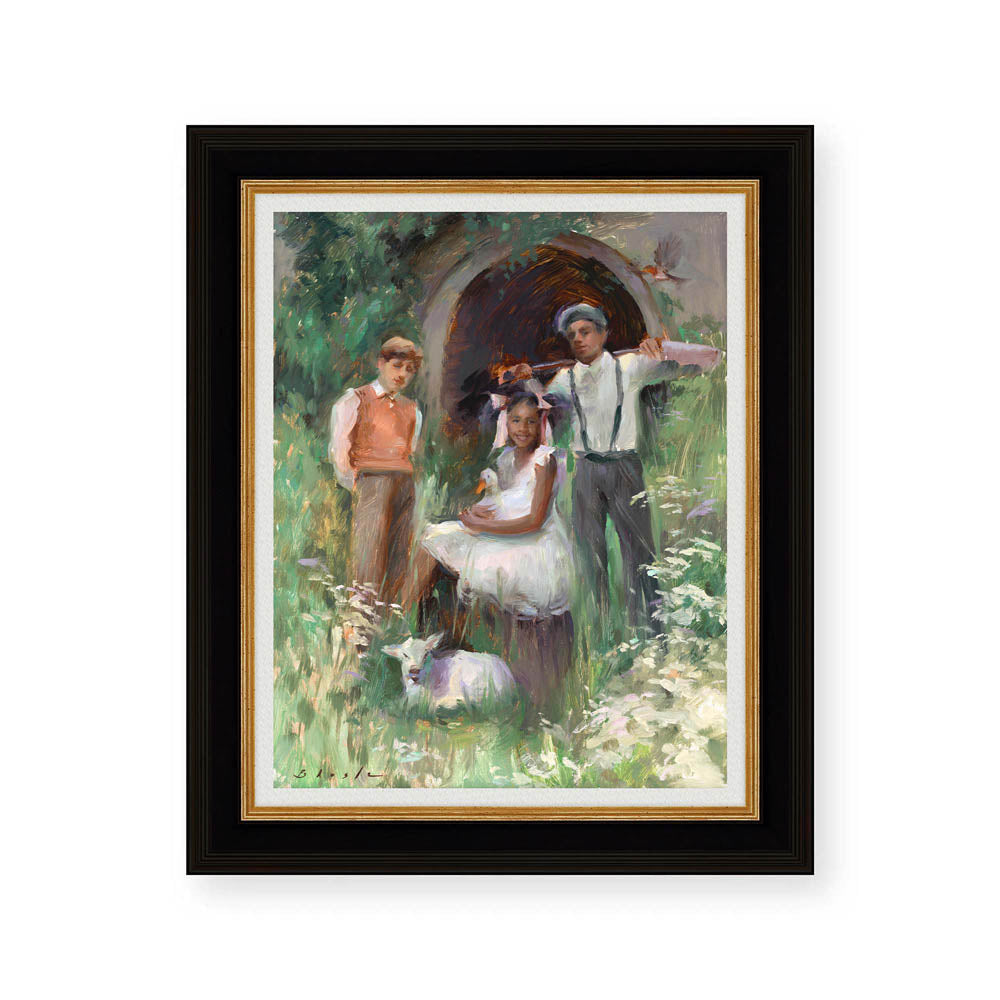

In joyful response to their presence, spring returns at last: once more the flowers bloom, the fruit trees blossom. The giant repents of his selfishness, demolishes the wall, welcomes the children, and is himself transformed by the love of a particular mysterious child who befriends him.

This of course rings the same archetypal bells as another beloved childhood classic, The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett.

The two tales are tantalizingly similar and yet significantly different. As were their authors, and the stories behind the stories, the winding roads that led to them.

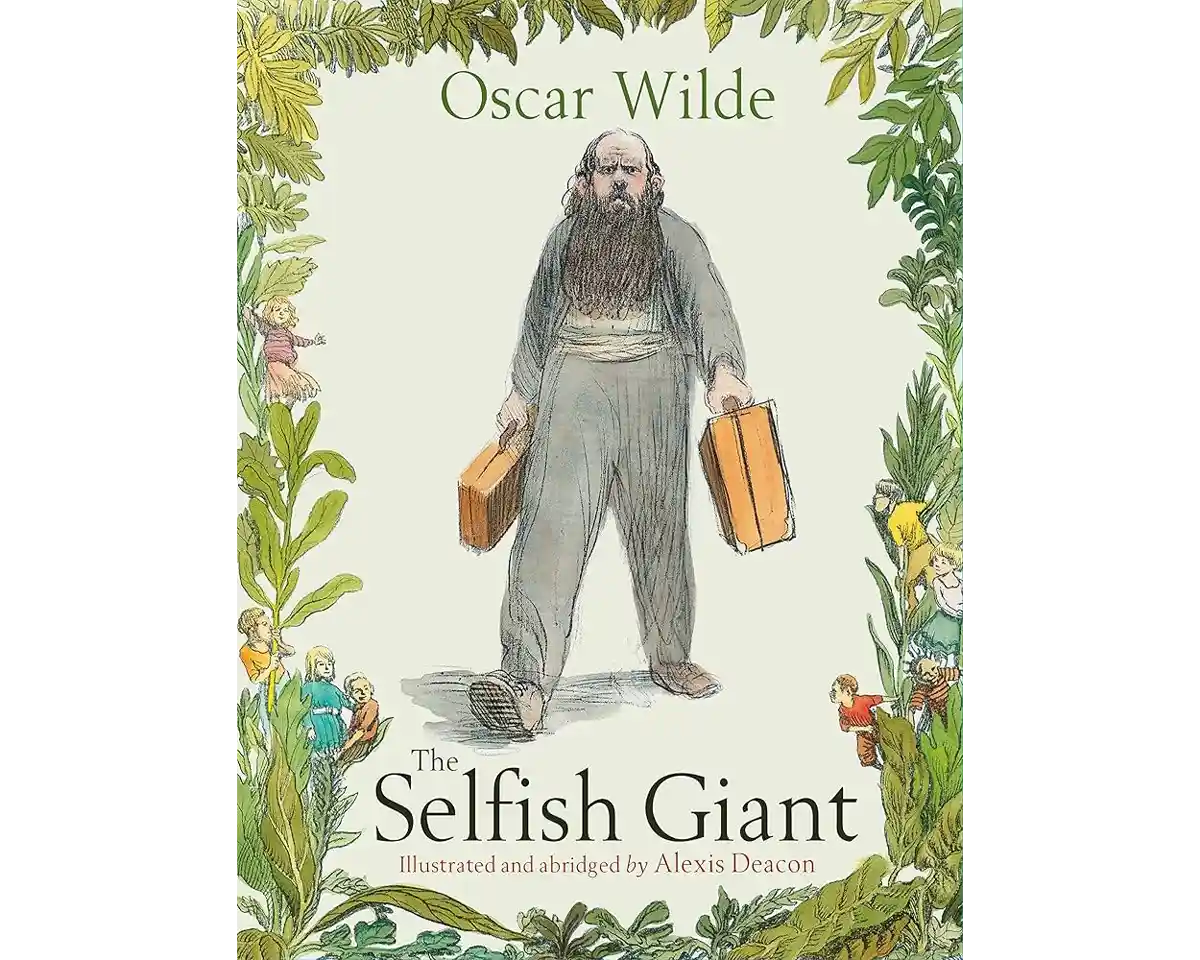

As a child I had no idea that Oscar Wilde, of the biting wit and scandalous reputation, had written The Selfish Giant. His name would have meant nothing to me anyway: I assumed that all fairy stories were sui generis, simply existing in their own right, sprung as the goddess Athena was said to have sprung fully formed from the head of Zeus. So any possible disconnect between the sweet sad story and its flamboyant author escaped me entirely.

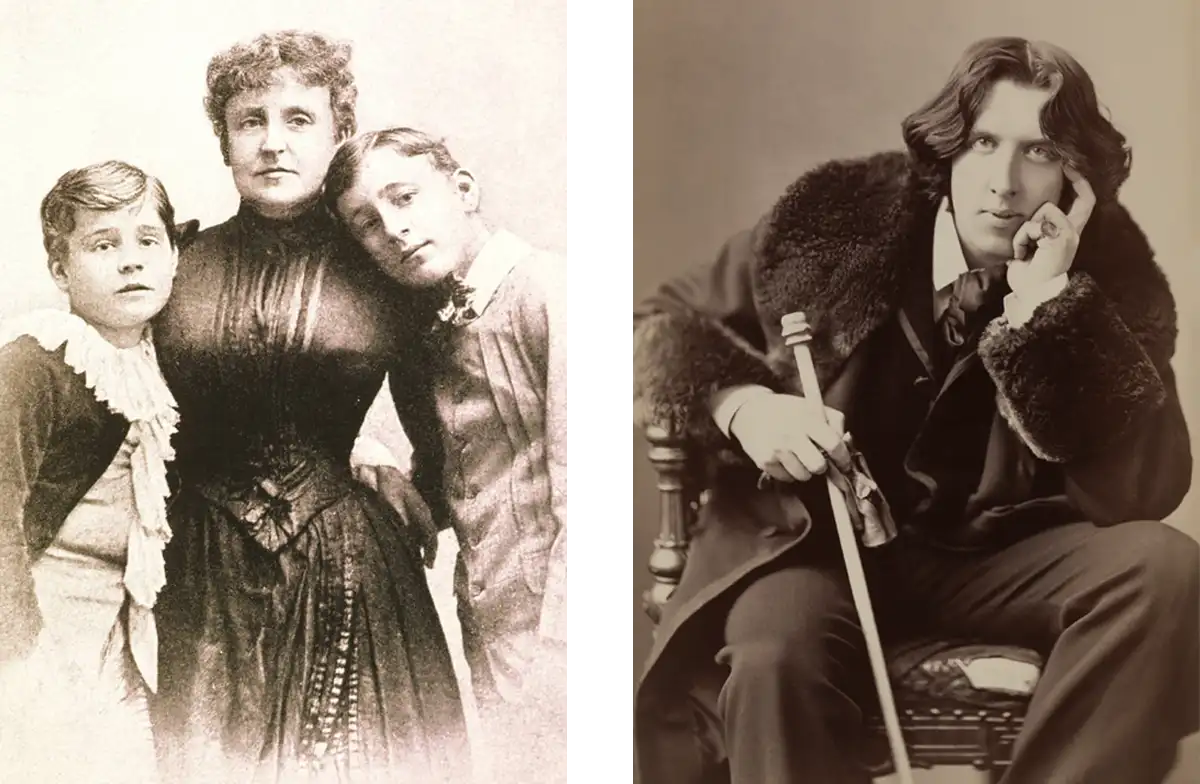

Improbably enough, a conjunction of these two literary planets occurred once upon a time: unconventional Oscar Wilde—famous in Victorian circles for his brilliant conversation, his satiric plays, his exaggeratedly aesthete style—and Frances Hodgson Burnett—successful author of popular sentimental novels, wife and mother, and hostess of a literary salon in her Washington D.C. home—actually met face to face one winter afternoon, and were apparently completely charmed by one another.

Wilde came to America in 1882 for a (wildly popular) year-long lecture tour, and while in Washington was invited to one of Frances’ literary salons. Apparently the two of them hit it off immediately, and spent the entire afternoon in a corner together in animated conversation, ignoring all of the other guests.

I wonder what they talked about.

They might have explored the idea of writing for children, which at the time was still largely unexplored territory for them both.

Oscar Wilde would soon marry, and would have two sons, one of whom would later recall that his father often told them fairy stories of his own creation.

Wilde published The Happy Prince and Other Tales (including The Selfish Giant) in 1888, six years after that afternoon with Frances.

The Selfish Giant is the most enduringly popular of Wilde’s children’s stories: it has been separately published in countless illustrated editions since it first appeared in 1888.

* * *

The crux of the story is a mysterious little boy who is too small to reach the branches of the trees the other children climb. He stands weeping in the garden until the Giant takes pity on him and lifts him up into the tree. The little boy throws his arms around the Giant and kisses him. But this child does not return to the garden, and the other children, who had never seen him before, cannot tell the Giant where he has gone.

Years later, when the Giant is old and weary, the little boy returns.

Overjoyed, the Giant runs to greet him, but is horrified when he sees that the child’s hands and bare feet bear the marks of nails. “Who hath dared to wound thee?” cried the Giant; “tell me that I may slay him.” “Nay," answered the child: “these are the wounds of Love.”

The child (now clearly meant as the Christ Child, although he never gives his name) smiles at the Giant and says, “You let me play once in your garden; today you shall come with me to my garden, which is Paradise.”

When the other children come to the garden later, they find the Giant lying dead, covered with fallen blossoms.

* * *

There is something almost eerily prescient in the tone of all the stories for children that Wilde wrote: a deep current of sadness runs below the surface. They were published when he was at the height of his success, but seem to foreshadow sorrows to come.

Also, Wilde had been acquainted with grief from an early age: his beloved little sister Isola died of a fever when she was nine, and he was twelve. He was devastated by this loss, wrote his first published poem Requiescat for her, and carried a lock of her hair with him for the rest of his life.

Wilde would also, in a way, lose both of his much-loved sons. After his notorious trial, conviction, and imprisonment, sentenced to two years hard labor for the crime of “gross indecency” when his affair with Lord Alfred Douglas became known, Wilde was never allowed to see his sons again.

Upon his release from prison in 1897, he was a man broken in body and spirit. He wrote to a friend that, under the brutal prison conditions, life “had torn him like a tiger.” He left for France the night of his release, and never returned to England.

Disgraced, penniless, ill, and alone, he died at the age of 46, of meningitis (brought on by a head injury sustained in prison), in a shabby hotel room in 1900.

There is an almost hidden thread running throughout this fabric: the story of his complex relationship with Catholicism. Born into a prominent Anglo-Irish family, he was, as custom dictated, baptized as an infant in the Anglican parish church in Dublin, but secretly baptized Catholic at the behest of his (secretly) Catholic mother. His fascination with the Catholic Church was complicated, but lifelong.

As he lay dying in Paris, he asked that a priest be brought, and he was received into the Catholic Church and given sacramental last rites.

* * *

I am convinced that Frances Hodgson Burnett would have read The Selfish Giant when it was published in 1888; she would have loved it, and the resonance with her subsequent Secret Garden is too strong to be a coincidence. I like to think Wilde would have sent her an inscribed copy, but whether he did or not, his influence on her own Garden (published in 1911) is unmistakable.

In fact, influence is too small a word. It is more as though they sang from the same hymnal, as the Quakers say. Or were even singing the same song, a duet in two-part harmony.

In both tales, gardens are created, then lost: through neglect, wintry selfishness, or grief that locks the heart. The gardens are discovered and restored, and the embittered characters redeemed, by the innocence and love of large-hearted children, and by the healing power of nature, the “greening power of God.”

In The Secret Garden, as in Wilde’s stories, there runs a subterranean current of grief: Frances’ beloved first-born son Lionel died in 1890, aged 16, of tuberculosis. His mother never really recovered from that loss.

Shattered, and finding no consolation in her traditional Anglican faith, she sought and found deeper comfort in the alternative spiritualities popular at the time: Christian Science, Theosophy, positive thinking, the healing power of nature—all of which are prominent in The Secret Garden.

Wilde’s and Frances’ religious quests followed almost inverse arcs—his deathbed conversion rooted in his infancy, leading him back to his mother’s Catholicism—her journey leaving conventional religion behind.

I hope they both found the healing, reconciliation and love—the Magic, whatever we call it—that their most famous children’s stories have celebrated and conveyed to so many.

I especially hope they both found the peace they had always longed for, beyond the walls of all gardens, beyond the walls of the world.

Deborah Smith Douglas has been an avid reader all her life. She has also been a lawyer, a writer and editor, an operator of both a drill press and a switchboard, a wife and mother, a really bad skier, and a worse poker player. She is the author of two and a half books, more about all of which can be found at deborahsmithdouglas.com.