The book he had been preparing to write his entire life, John Steinbeck’s eleventh novel and magnum opus, East of Eden (1952), has long captivated American readers with its layered exploration of the human struggle between good and evil, played out through two generations of American families. Set in Steinbeck’s home region of California’s Salinas Valley, the Trask and Hamilton families face reckonings as members come to grips with their identities and past. What, perhaps, has made this family saga stick so firmly in the American imagination is Steinbeck’s complex portrayal of the American Dream and his unsettling suggestion that it may be unattainable, or too fragile to “achieve” consciously.

East of Eden doesn’t just examine the American Dream, it shatters it, exposing the illusions and sacrifices hidden beneath its promise. With a Netflix limited-series remake of the novel currently in development starring Florence Pugh, Steinbeck’s warning feels as relevant as ever: the American Dream continues to seduce and disappoint those who chase it. Here are five ways Steinbeck exposes the faultlines beneath America’s utopian idealism:

1. The Dream Promised a Family, but Delivered Isolation

At the heart of Steinbeck’s retelling of the Biblical Cain and Abel story is Adam Trask, a U.S. Army veteran living in the late 1800s who is forced into service by his domineering father, only to find himself adrift after being discharged. He eventually moves to California with his new bride, Cathy, to begin a successful farm—a symbolic “Eden”—but his dreams are soon shattered. He clings to the idea of a family unit and is thrilled at the news of Cathy’s pregnancy, but becomes devastated when she abandons their family only weeks after giving birth to twins. Despite his gradual acceptance of being a single father—thanks largely to the support of his housekeeper and confidant, Lee—he never fully recovers from her abandonment or the shattering of the life he imagined for himself.

2. The Dream of the Frontier Was Never Real

Adam’s story runs in tandem with the peak of Westward Expansion, as white settlers claimed “manifest destiny”—the alleged God-given right to claim lands populated by Indigenous people. Whites viewed this vast land as an opportunity to become rich and start again, though it usually proved futile, with many struggling to find the success they had been promised. This promise entices Adam, allowing him to escape the weight of his restrictive past and wartime trauma to start again. Long associated with a fulfilling life, California’s agricultural potential represents the stability Adam yearns for after an isolated childhood spent in fear of his violent brother, Charles. But we now know, many of the pioneers who pursued this dream did not find salvation, only struggle. Steinbeck’s Salinas Valley, far from being a promised land, mirrors the emptiness of those who inhabit it. The soil that was supposed to revive pioneers’ spirits instead offers loneliness and the impossibility of true reinvention. The “new beginning” America promised was already haunted by what it destroyed.

3. Success for Women Requires Extraordinary Behavior

Adam’s naïveté allows him to overlook the fact that Cathy, whom Steinbeck describes as a “born monster,” is a highly adept manipulator, especially when it comes to men. After shooting Adam in the shoulder before abandoning the family, she joins a brothel, where, through unscrupulous means, she becomes its madam. While the women’s rights movement was gaining steam post-Civil War, it was decades away from creating definitive change. Portrayed in stark contrast to Adam’s goodness, Cathy is cynical of the human race’s capability for good. Yet, Cathy’s character allows Steinbeck to explore how differently the Dream plays out for women; at the time, wives were viewed as their husband’s property and lacked legal rights to any money or land they may have had before marriage, leaving Cathy with few legitimate paths to power. Her motives may seem clouded, but what she truly seeks is financial stability and the concealment of her checkered past. She embodies the American ideal of reinvention—at its most ruthless and deceptive—continually changing her name and image to outsmart others and secure control in a world that offers her no rightful place to do so. Sadly, she eventually witnesses her son’s disgust with his own mother, realizing she has created a void in her life with the singular pursuit of insulating herself from a world she believes is set out against her.

4. For Many, the Dream Requires Assimilation and Concealment

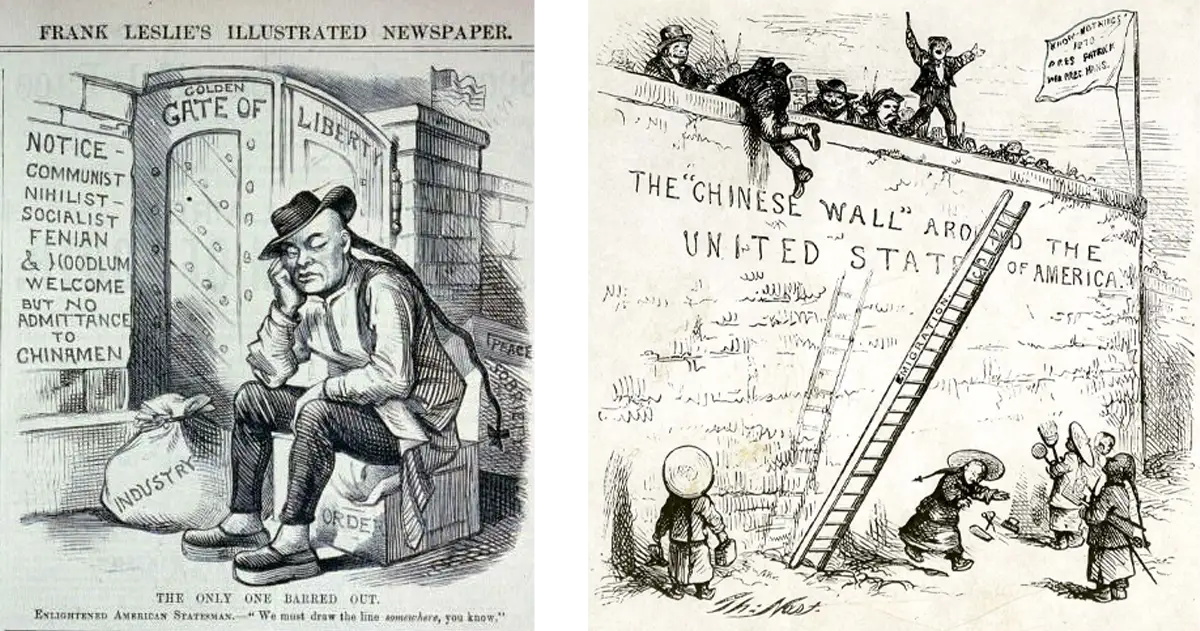

Through the character of Lee, an Asian American, Steinbeck complicates simplistic visions of the American Dream, exposing the barriers immigrants faced when seeking its fulfillment. The only nonwhite character in the novel, Lee, at first glance, appears to accept society’s race-based hierarchies. Content in his role as a domestic for a white family, he regrets not having a family of his own but takes pride in keeping the Trasks together. After Cathy’s departure, Lee stands by Adam and the twins, yet gradually reveals his own trauma, including the murder of his mother, who worked on a railroad gang.

Encouraged by Adam’s morally sound neighbor Samuel Hamilton, Lee stops code-switching and is embraced by the Trasks for his philosophical wisdom. Steinbeck highlights both the influx of Chinese immigrants to the West Coast and the racism they faced, often being stereotyped as strikebreakers. The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act banned Chinese immigration for a decade, yet discrimination endured, severely limiting professional opportunities.

Each of these characters is forced to live a reality that differs vastly from their dreams, shattering their expectations for life in America. While some critics read East of Eden as moralistic, Steinbeck’s treatment of the American Dream is more fluid. Ultimately, he suggests that the Dream is evasive—something that can’t be gained by active pursuit. Aiming for inflexible outcomes doesn’t guarantee success; the journey to fulfillment requires adjusting on the fly, especially when the cultural and societal landscape is not built in your favor.

5. A “Better Life” is—and Always Will Be—Subjective

After all, the American Dream is only a phrase, an ideal, a vague concept that still holds cultural power, despite its lack of definition. Ultimately, nearly every character in the novel realizes that their life doesn’t unfold in the idealized way they initially imagined it would. Steinbeck shows us that striving to create a “better life” in America is highly subjective—then as it is now. Having good intentions isn’t enough to guarantee your wishes will come true, especially in a society driven by ambition and competition. That’s not to say we shouldn't strive—we will always regret missed opportunities and closed doors—but that doesn’t mean we should have unrealistic expectations for what is ahead. Living life for its own sake and making conscious choices may be the truest way to secure a life well-lived. As the wise and philosophical Lee says: “And now that you don't have to be perfect, you can be good.”