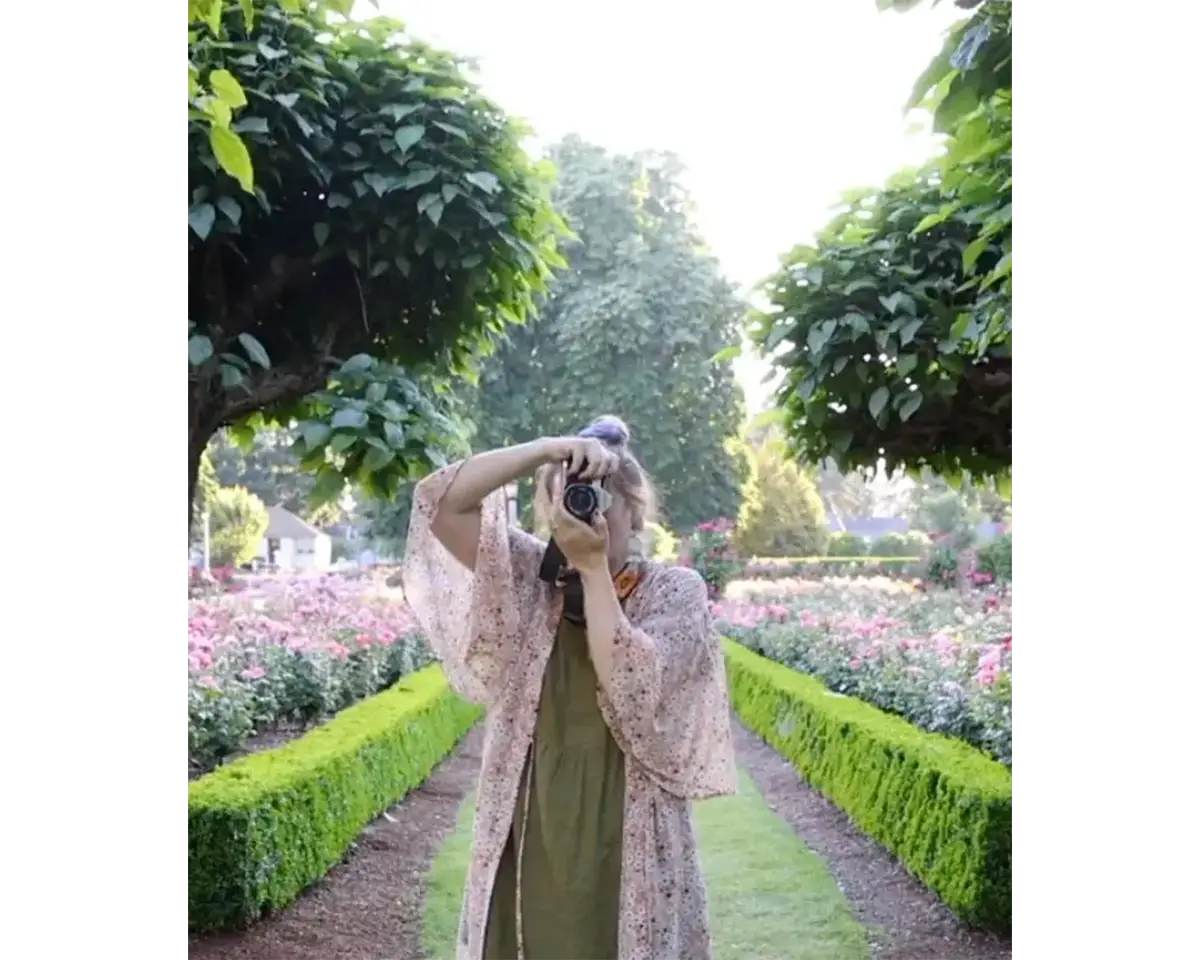

Upon first glance, there is little similarity between the artwork of Theresa Bear and Brenna K. Murphy. Firstly is the difference of medium. Theresa is a photographer and botanical artist, creating poised and meticulous scenes depicting the beauty of nature. Brenna’s work is hand-embroidered, an accumulation of thousands of tiny stitches. Theresa currently lives in Portland, Oregon, Brenna in East Germany. Theresa is radiant and passionate, Brenna in possession of a stillness that evokes a quiet wisdom.

There is a curated quality to Theresa’s work that contrasts with the natural world she celebrates: bushels of flowers in an indoor studio, a man in a crisp suit with the head of a bird, sharp blazers and lace gloves filled with soil. Her scenes are highly controlled and yet have an air of spontaneity and whimsy.

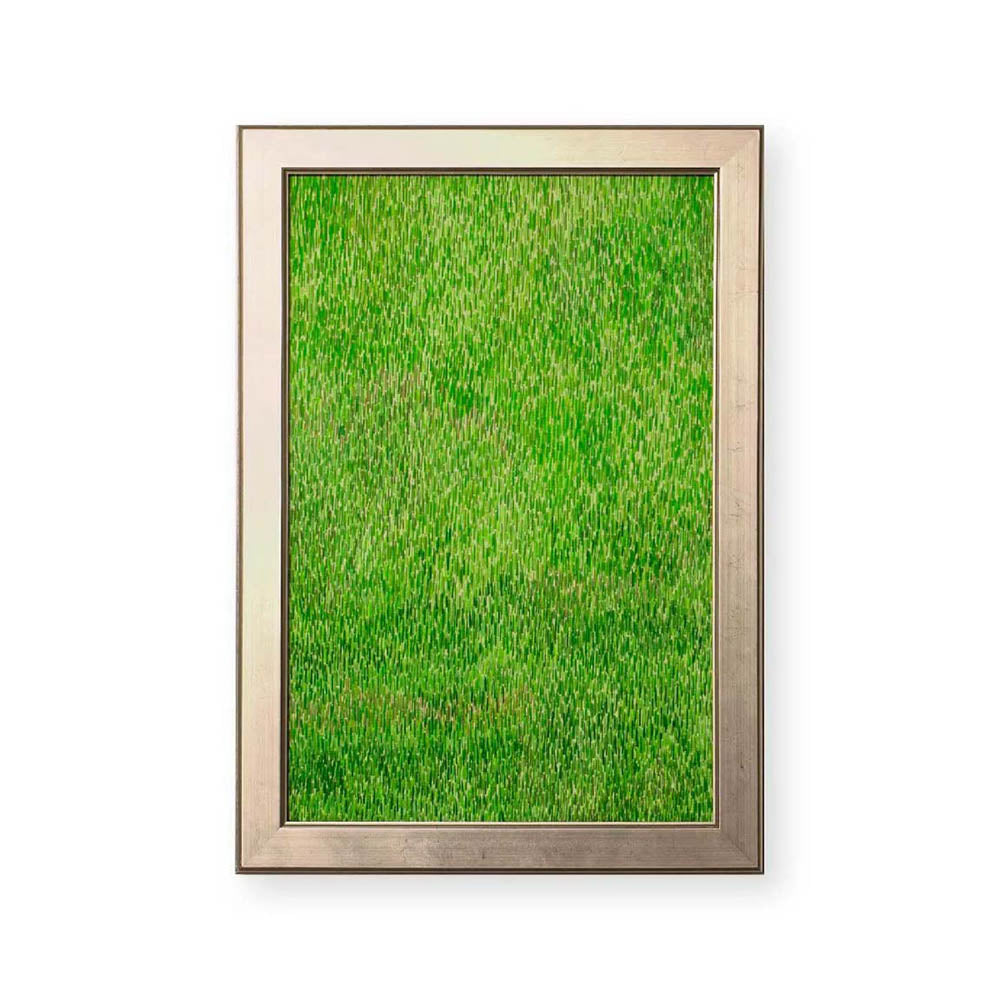

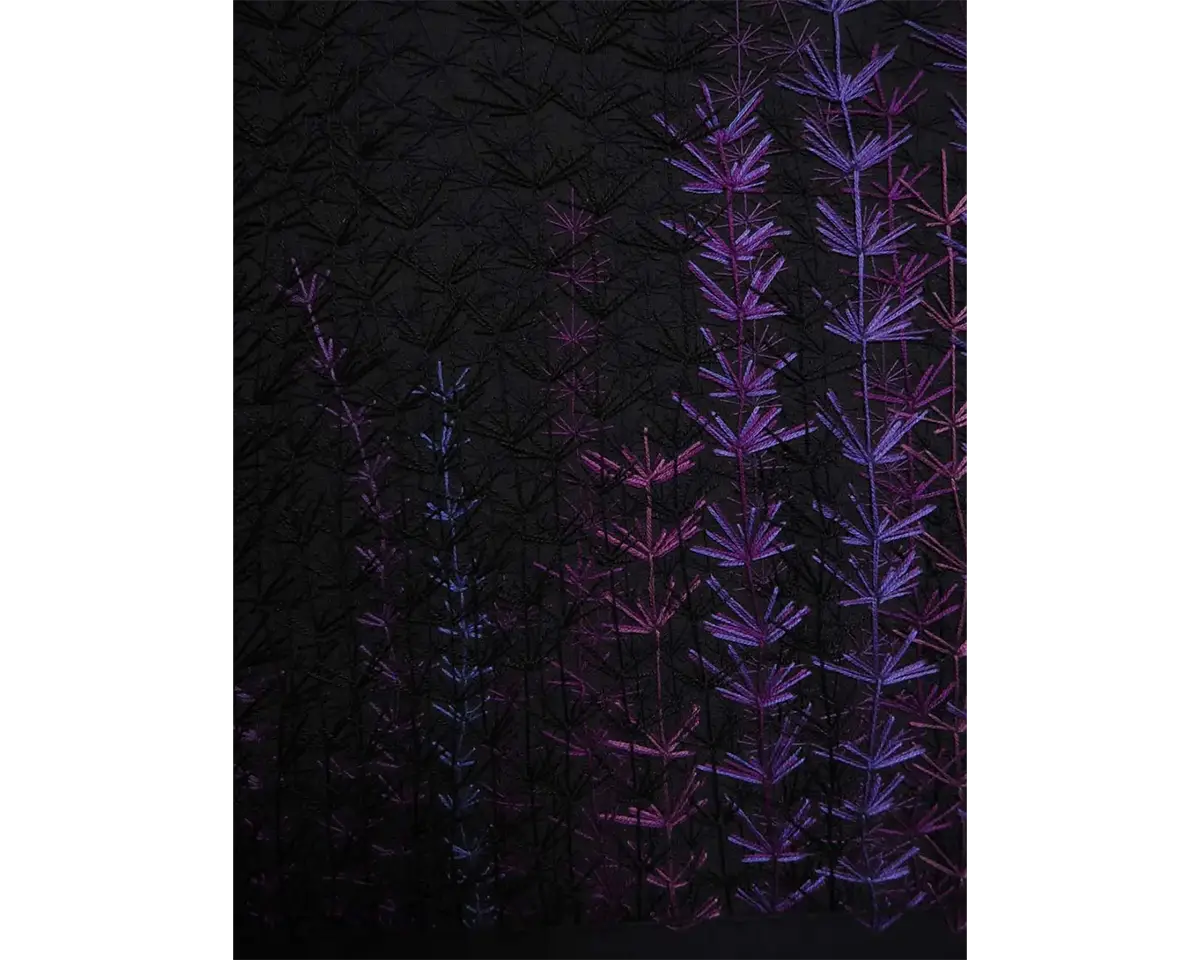

Brenna’s work is subtle and striking, the repetition of thousands of embroidered threads. From a distance it may seem uniform, but on closer inspection her pieces come alive with subtle variations. Through a transition from black to purple or a million varieties of green, Brenna’s work celebrates the wonders of nature on the most intimate of scales.

Even with very different final products, both artists find solace and inspiration in their depictions of the natural world. Both were selected by Bond & Grace to create work for The Secret Garden Art Novel, not despite their differences, but because of them.

We sat down with Theresa and Brenna to discuss their practice, what inspired them about Frances Hodgson Burnett’s classic novel, and progress and inclusion in the art world.

Both Artists see their work as a way of processing and interpreting the world around them. “When I make art, it’s my way of trying to understand the world and process my emotions,” Theresa says.

Brenna remarks something similar, saying “For me, the purpose of art is to process and interpret the human experience. That’s what artists do.” For both, the term process is important. But how does the act of processing play out in each of their practices?

For Theresa, it is highly collaborative. Each of her photographs takes a village, and she reaches out to a wide network of friends and fellow-artists to come together in service of the world she strives to build “If something inspires me, if I’m going for a walk and I see some kind of metaphor in nature, I sketch it out,” she says. “Then my process usually involves people. I know I’m going to need models, if I need models I need a makeup artist. I’m going to need my flower friends, I’m going to need studio space. I then make a mood board and pick the color scheme, I think about the poses and the mood, I think about what music I’m going to play when I take the photos, it’s down to the very detail. But my favorite part is that other people’s art becomes a part of my art, and then it’s our art.”

For Brenna, whose work is all hand-embroidered, the art-making process is laborious and physically strenuous. She sees a link between the solitude and long-hours her work demands, and the body’s response to grief. “Previously I was making work about home and loss,” Brenna says. “And then I started to shift into grief specifically because I lost my best friend in 2016 when I first started my grad program at the University of Michigan. We process grief cognitively and emotionally, but what about physically? How does grief live in your body? How does it make you move? For me, the answer was always artistic labor. I need to make something, my hands have to be doing something. That was my intuitive, instinctual response to the grief I was experiencing.”

Both Brenna’s grief and Theresa’s community are reflected in Frances Hodgson Burnett’s work. In The Secret Garden, multiple characters experience grief of their own. Mary is abandoned and isolated; having been neglected by her parents even before their passing. Similarly, Colin has lost his mother and is ignored by his father. He grieves for a life he thinks he will never get to experience. Archibald Craven has been in a deep depression since the death of his wife. Yet it is the love and community provided by Dickon, Martha, Ben Weatherstaff and the many animals that surround them that return life to the bereaved characters and the garden alike.

For Theresa, this metaphor was particularly powerful. “What I loved about the book was the theme of nature being medicine, but also friendship and how the garden is healing. [The children] being together is so restorative you can see the garden grow as their friendship grows,” she says.

This linear trajectory from grief to recovery, sickness to health, while a satisfying narrative structure, is not always true to life. This was something Brenna intentionally focused on in her response to the text. “Part of my work was responding to the way [Frances Hodgson Burnett] wraps things up and by magic everyone is better,” Brenna says.

“It’s not like you flip a switch and magically it’s over. Everyone is working really hard, they are doing the labor of grief, the labor of depression, the labor of self-introspection. That was one of the reasons I wanted to do the really laborious process of embroidery and stitching. It takes time; you’re bent over and your shoulders hurt and your hands hurt. Grief is work. That was my major critique of the book and something I was lovingly trying to put in my pieces.”

Another theme present in both the book and the work of the Artists is the hyper-specificity of place. Much of the plot of The Secret Garden is reliant on the environment in which it occurs. Misselthwaite Manor and the Moor serve as a character with as much impact and agency as Mary, Dickon, and Colin. Similarly, Theresa sees her home in Portland, Oregon and the environment of the Pacific Northwest as being fundamental to her work. “When I go out in nature, I find all the answers I need,” she says “The Pacific Northwest has so much accessibility to nature, which unfortunately we don’t have everywhere in the world anymore. I’m thirty minutes from a waterfall, I’m a little over an hour from the beach, I can go to a desert, I can go to a mountain, it’s a 20 minute drive to a forest. That kind of access for me and my family is what makes me really rich and inspires my art.”

Brenna also sees place as a deciding factor in her art, but in a different way. Rather than a connection to a specific location, she sees placelessness influencing her work. “For me personally, my art has always come from my own lived experience, particularly having this nomadic upbringing where I moved around every few years from the time I was born until the time I moved to Philly after my undergraduate college years. I didn’t have that childhood home in the same house. I had none of that,” she says. “My studio is in boxes, so I am always working from this internal space that stays with me wherever I am on a map.”

Although different and unique in their own ways, by considering Theresa and Brenna’s work side-by-side we can gain a deeper understanding of the subject matter. Both are in agreement that broader inclusion of artists from diverse backgrounds is critical to the success of the art world, and our understanding of what art can accomplish. “I think the most important and beautiful thing we’re witnessing right now is the representation of people who have never had the microphone, camera, or paintbrush,” Theresa says. “We’re seeing it like we’ve never seen it before. I would be so bold to say it is another Renaissance. Through seeing other people’s work that we’ve never seen before, it makes us aware of so many more stories and so many more emotions that we haven’t personally given space for.”

Brenna agrees and emphasizes the cumulative aspect of creative work leading to social progress. “It’s not just one photograph or one novel, but all of these things over time, and then you combine that with people in the world and their lived experience. These things come together, and you have allies that have shown up because they have encountered the art that is helping them grow awareness and empathy.”

With a single thread and the flash of a camera, Brenna and Theresa’s work helps us interpret a much-beloved story in new ways, and in doing so we become agents for progress; nurturing our own gardens both large and small.

Listen to our full conversation with Brenna K. Murphy and Theresa Bear here