Growing up in the suburbs of Oregon, the Beaverton City Library was my Disneyland. To me, it felt like “the happiest place on earth,” only this holy place boasted large, twisty staircases instead of rollercoasters, aisles of books instead of aisles of gift shops, and knowledgeable librarians rather than Mickey Mouse and his crew of costumed characters. My mom and dad would bribe my sibling and me to do our summer math workbooks, but when it came to reading, we didn’t need any encouragement.

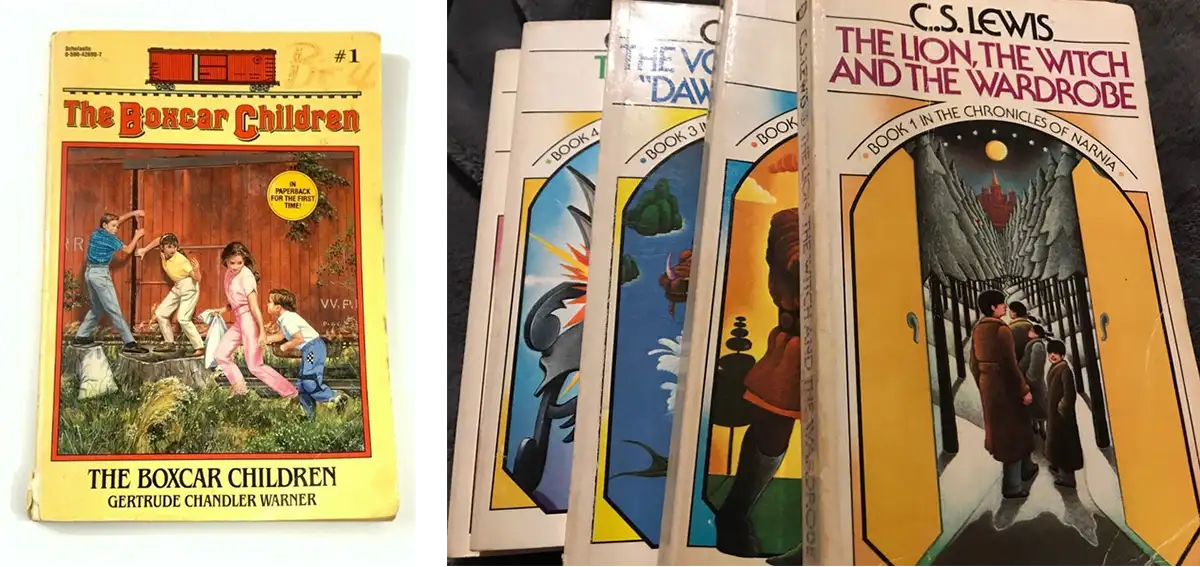

In old photographs, stacks of reading material for all ages pile across our shelves. Memories of evenings spent with all of us curled up on the quilt of my parents’ bed—the stories coming alive through voice—will never leave me. My mom read us The Boxcar Children, picking up the next book in the series just as the one before it wrapped up. My dad chose The Chronicles of Narnia, and we were captivated by the exciting tales, and even the ones that had less adventure in the plot, like The Magician’s Nephew.

Now, looking back, it becomes clear that my sibling Emma and I were always big readers because that behavior was modeled for us, and encouraged from day one. The last time my family was in town we found our conversation returning to books, like it usually does when we’re together. How lucky we were to grow up in a colorful world of literature!

Silent sustained reading time was big in our home; my parents were always reading. My mom, who was a technical writer for many years before deciding to stay at home with my sibling and me, read mostly historical fiction and memoirs. I remember the books my uncle recommended to her, like Erik Larson’s historical works, and how much she talked about them as she read. She showed me how to truly comprehend what I was reading and how to share that knowledge with the world.

When chatting over the phone recently, my mom and I connected over the powerful phenomenon that reading brought us—the characters we were reading about became our friends. They modeled behaviors we wanted to incorporate into our lives, teaching us values of bravery and friendship and loyalty. My mom was really the one who helped books become so important in my life. She provided us with that refuge, and to use her words, urged us to see books as “a window and mirror.”

My dad worked in IT at Nike, so sometimes he brought home big books on new team management styles or technology he’d use at work, but mostly, he read science fiction. We laughed together about the number 42 holding the meaning of life, as Douglas Adams suggests in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, and the idea that books can stretch the limits of our minds became ingrained in me.

I have this specific memory of a book my dad read to me as a child. At some point in this book a young person asks a large, old oak tree for a branch to make into a magic wand. The tree requests for them to swing on the branches one more time, in exchange for the wand. To this day, I haven’t figured out what the book is (in every Google search, The Giving Tree pops up), but the scene will never leave me. The way we interact with nature and what we leave behind as we grow are themes that have stuck, reminding me to hold onto my imagination and sense of wonder.

I recently spoke to my grandma on my mom’s side about her reading experiences too, and was intrigued when she told me that as a child, reading was hard for her. My great-grandparents worked hard to raise my grandmother and her siblings, but there was a different level of access to books in their familial situation than in mine. Having immigrated from Croatia to Illinois, they didn’t keep books in their home, rarely went to the library, and her mom and dad didn’t read very much themselves. Even still, her identity, in my mind, has always been intertwined with her love of reading.

Grandma decided to start reading in adulthood because her husband, my grandpa, encouraged her to “do more and be more.” Once she started reading, every book, every character, kept her wanting more, eager to pick up the next novel before the one she was reading was done. She also talks about wanting to work to create reading habits in the lives of those around her—-including her children.

Returning to my mom, it turns out that her reading story is also connected to my grandpa. She says she became a reader on his lap. She remembers cozying up with him on grandma’s recliner, surrounded by stacks of books, their voices intertwining as they repeated the refrain in The Little Engine That Could in synchronicity: “I think I can, I think I can.” This reading environment was absent from my grandma’s life as a child, but because my grandma worked hard to prioritize reading, she was able to build that world for my mom, and in turn, for me.

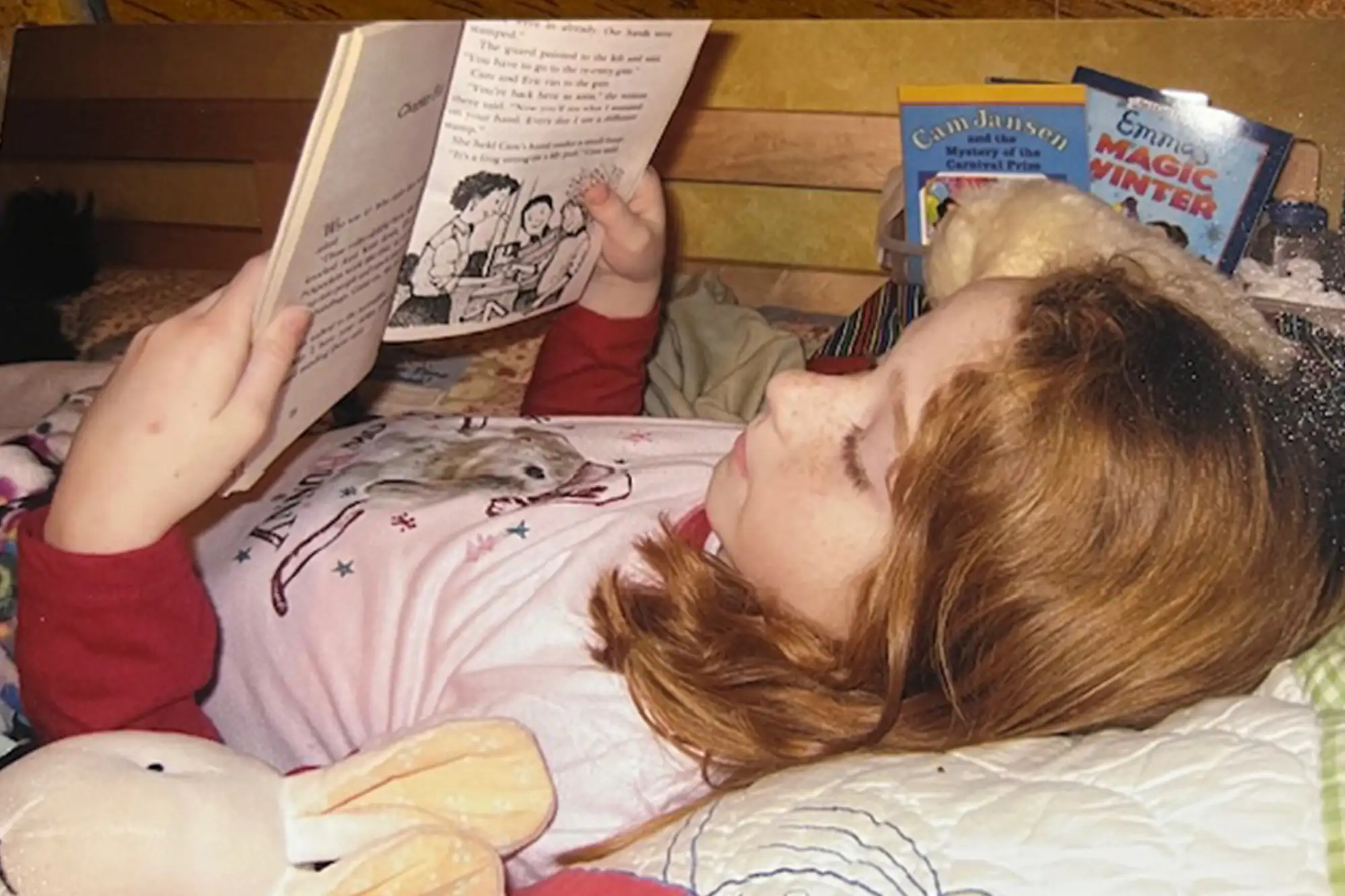

For my mom, reading on her grandma’s lap was security, something I can relate to. Money was tight and they moved often, but love, and a love of reading, was overflowing. While I didn’t move until I was twelve, and I was privileged to not have to worry about finances, I completely understand the way reading feels safe. Multiple chronic illnesses crisscrossed my life, leading me to spend my days in hospitals and doctor’s offices, but books were a constant in my childhood and always there for me when everything else felt rocky. It started with Pat the Bunny, when I was young and first undergoing the diagnosis process—I brought both the book and the bunny stuffie with me to appointments. From there it turned into chapter books, fantasy novels like Percy Jackson and the Olympians, books with strong character development and settings that allowed me to escape.

My mom believes strongly that access to books and reading opportunities at a young age leads to lifelong reading. I know that’s true; because of my grandpa’s presence in our lives, everyone in my family loves to read. His kids modeled that behavior, and because they encouraged my reading, so do I. When my chronic health conditions flare up and I find myself returning to Percy Jackson and his demigod friends, I feel comforted by the nostalgia of it all, and so grateful that my family introduced me to books. Trickle-down economics doesn’t work, but trickle-down reading does, I suppose.

While I was in elementary school, my mom returned to school to get certified as a school librarian. She is working to become a bibliotherapist, and claims she has yet to become one—to which I disagree. As a librarian at the University of Michigan Law Library, she has helped various students, professors, and lawyers alike find access to vital information that could change a homework assignment, case, or even someone’s life. She makes information more accessible to all those who enter through the big wooden doors of the reading room. Before entering the world of law materials, she worked at a school library for 10 years, where she found books for young people that may not have solved their real-world problems, but impacted them in other ways. For kids navigating the effects of mass incarceration, she would present something like Milo Imagines the World. For young people struggling to make friends in class, she showed them We Don’t Eat Our Classmates. Children experiencing housing insecurity were given Stella Starliner. For her 15 or so years in a library setting, she has quietly made sure her patrons knew they were not alone, directly impacting the lives of her students one by one. So to that, I’d say that she’s as close to a bibliotherapist as one can get.

The love of reading that was instilled in me by my family, and the passion for accessibility that grew within me as I learned more about my disabilities, led me to pursue a master’s in library sciences. When my grandpa passed away, my grandma began looking for a meaningful way to give back to her community. Today, my mom still works at the law library, my grandma works at the Abraham Lincoln museum and library in Springfield, and I work at a queer bookstore in Chicago while pursuing my library degree at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

Because of the strong ties within my family, a love of reading has been passed down through generations, leading three of us to work in the book field, continuing to share the lifelong joy of getting lost in a story.