What is the relationship between an artist’s emotional state and the feelings evoked in their work? How does the mental state of one impact the other? How do working artists enact their desire for authentic expression? To find out, we sat down with Artists Julia Hacker and Maggie Lemak. Both spoke candidly about the relationship between their work and their mental health and helped illuminate the pain, joy, and process that goes on behind the canvas.

Julia Hacker specializes in large-scale abstract and contemporary landscape paintings. Her pieces are vivid and colorful and often incorporate a variety of mediums, such as print material, ink transfer, and textiles. The results are enormous and stunning pieces with striking emotional depth.

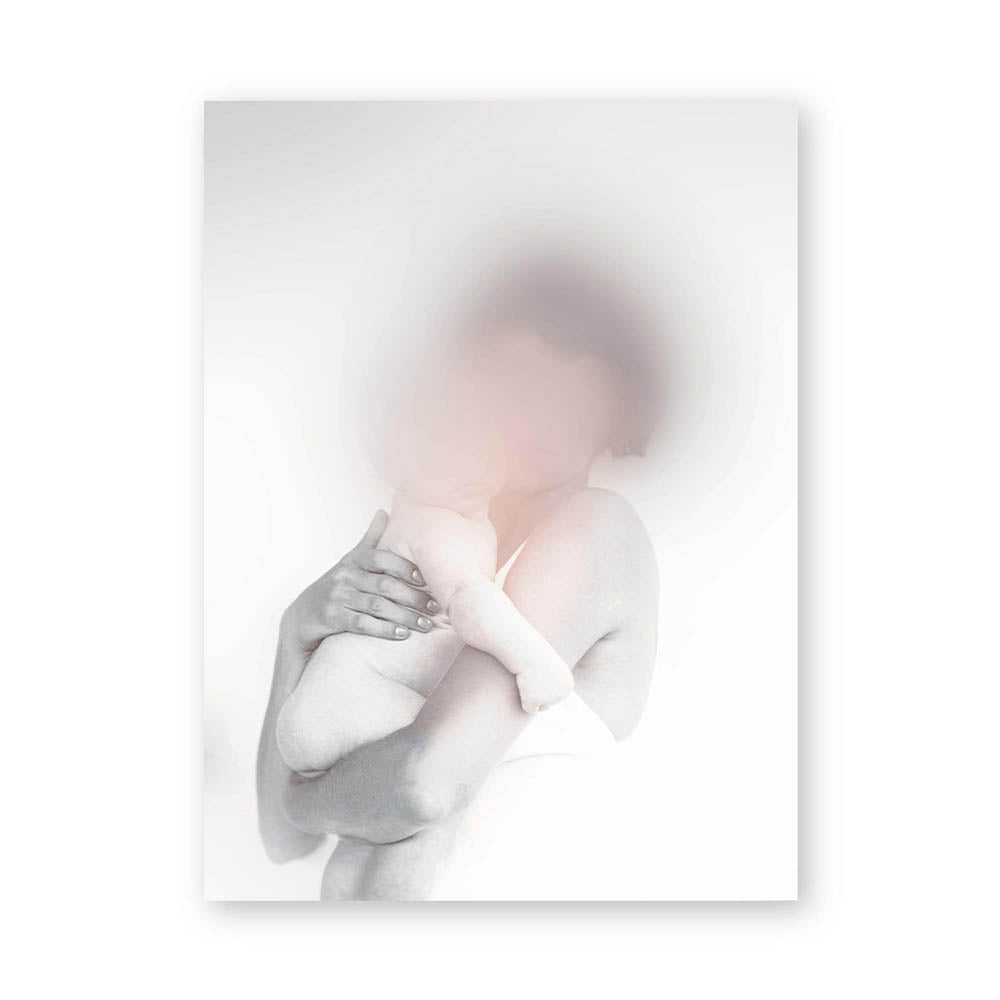

In her work, Maggie Lemak explores the fluid relationship between physical and emotional space. Like Julia, she works in a variety of media. Maggie uses her work to hone in on the emotional implications of physical sensations and how touch can serve as a conduit for empathy and intimacy.

It is difficult to consider the role mental health plays in art without thinking of the trope of the tortured artist. From Kurt Cobain to Vincent Van Gogh, popular imagination has forged a deep link between mental illness and creative expression. However poetic and painful Van Gogh’s decision to eat yellow paint may have been, the truth of the stereotype is up for debate.

“I think we are a bit tortured, we are emotional beings,” Maggie says of artists. “When I hear ‘the tortured artist’, I think of it as something centered around pity, but to me, it’s about being emotional and willing to share my emotions, which can be really empowering. That is the beauty of life, processing emotions through artwork and using artwork as a way to let them out. In many ways, we’re probably very healthy, because we do let it out.”

While Julia too feels a bit tortured at times, she recognizes that this trope is distinctly gendered. While we have long celebrated the genius of perceived madmen, women are rarely given the freedom to express such emotions openly and to the benefit of their careers. “The myth of the tortured artist was mostly male painters. I’m a mother, I’m a wife, as much as I am tortured, I have to perform other things in life. You still have to provide comfort, make dinner, wipe little noses. I just think that myth is outdated because this world consists of so many strong women, that no matter what turmoil they have inside, are moving on with their lives. You learn to live to be friends with torture and put it on the shelf while you cook dinner.”

Thankfully for both Julia and Maggie, art serves as a much-needed outlet. Their Art operates from a unique position as both product and influence–a reflection of their emotional landscape while simultaneously transforming it. “I have found that painting for me is almost a somatic experience because it gets so physical,” Julia says. “When you have no clarity emotionally when you’re in a really dark place and you start these kinds of strokes and colors, I realize that eventually, intuitively, by the time I finish painting, I will start seeing a pathway, some light in between.”

The canvas is not simply a product of Julia’s mental state, but a safe space in which she is able to work through complex emotions in physical and creative ways.

Maggie expresses something similar, going so far as to use the canvas, and the choices she makes in her creative practice, to reframe and reconsider her lived experiences. “A thread in some of my recent work has been taking a painting that I made in a dark time, and that I don’t like, and painting on top of it. I love that the painting itself has that history because it is reflective of who we are as people. We go through dark times and it doesn’t evaporate once it happens, it comes with you, but you can let the darkness become something beautiful when you paint on top of it.”

Maggie’s attitude towards reframing her work and her own personal experiences shares similarities with Frances Hodgson Burnett’s philosophy in The Secret Garden. Inspired by the natural life cycle of plants, Burnett saw past hardship not as a source of shame, but as fertile ground for new growth. Loss, pain, and grief, while all legitimate emotions are a fundamental part of life. They enrich the soil of future happiness the same way a dead tree will decompose in service of new life.

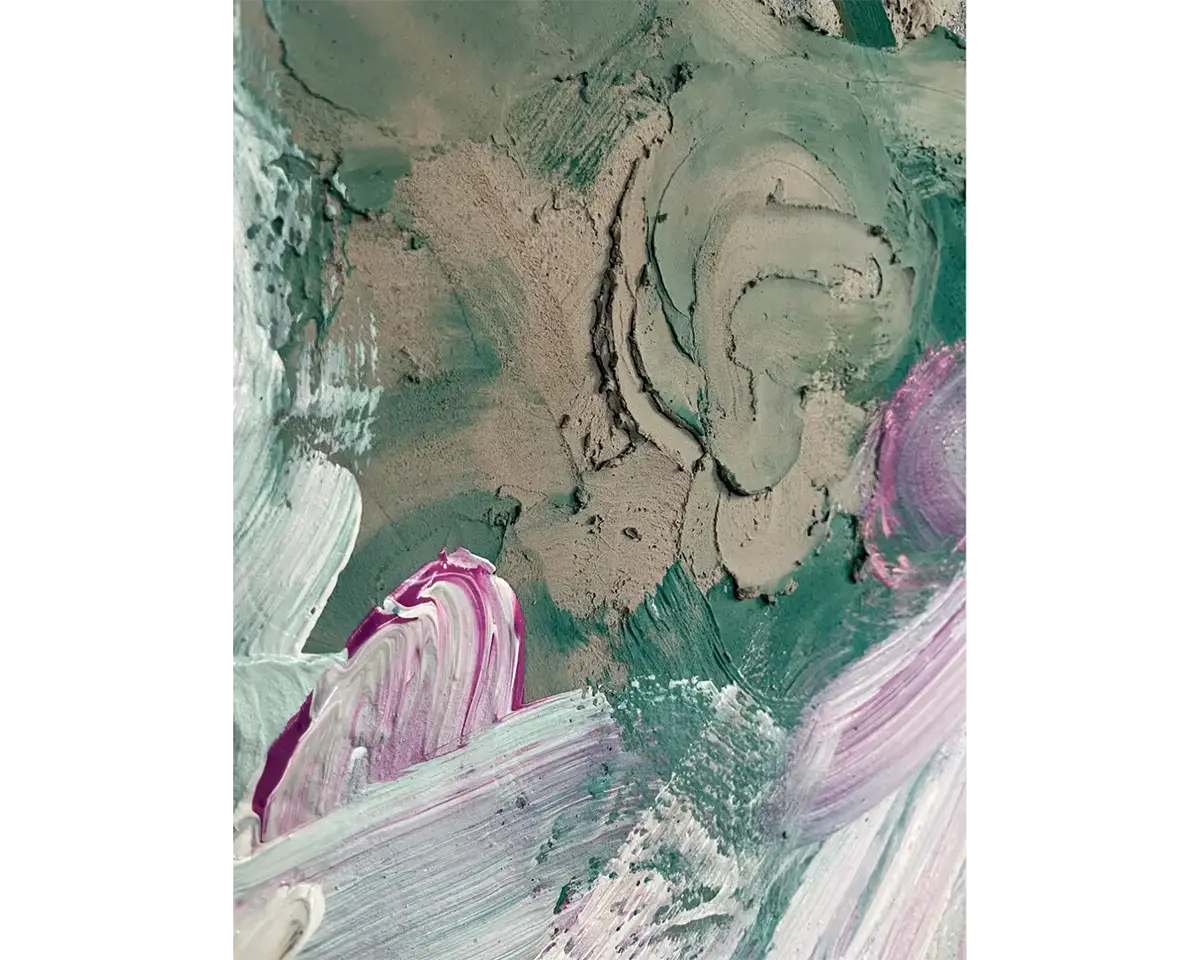

Maggie’s pieces in The Secret Garden Art Novel reflect this philosophy. Her painting Letting Walls Down Letting Passion In is acrylic paint on top of sections of rough concrete. A reference to the garden paths used by Mary in the novel, the harsh, unlovely material gives the painting added texture and geography. “I’ve always been fascinated by concrete,” Maggie says of this decision. “I grew up in Florida and so I was always running around barefoot and I remember the heat of the concrete on your feet. I think it’s a really interesting material and a great symbol of that emotional wall. I didn’t want to let people in, I didn’t want to let my feelings out. But with the second layer after the concrete, it transformed from this rigid, cold painting into something free.”

Like Maggie, Julia is no stranger to incorporating unlikely materials into her work.

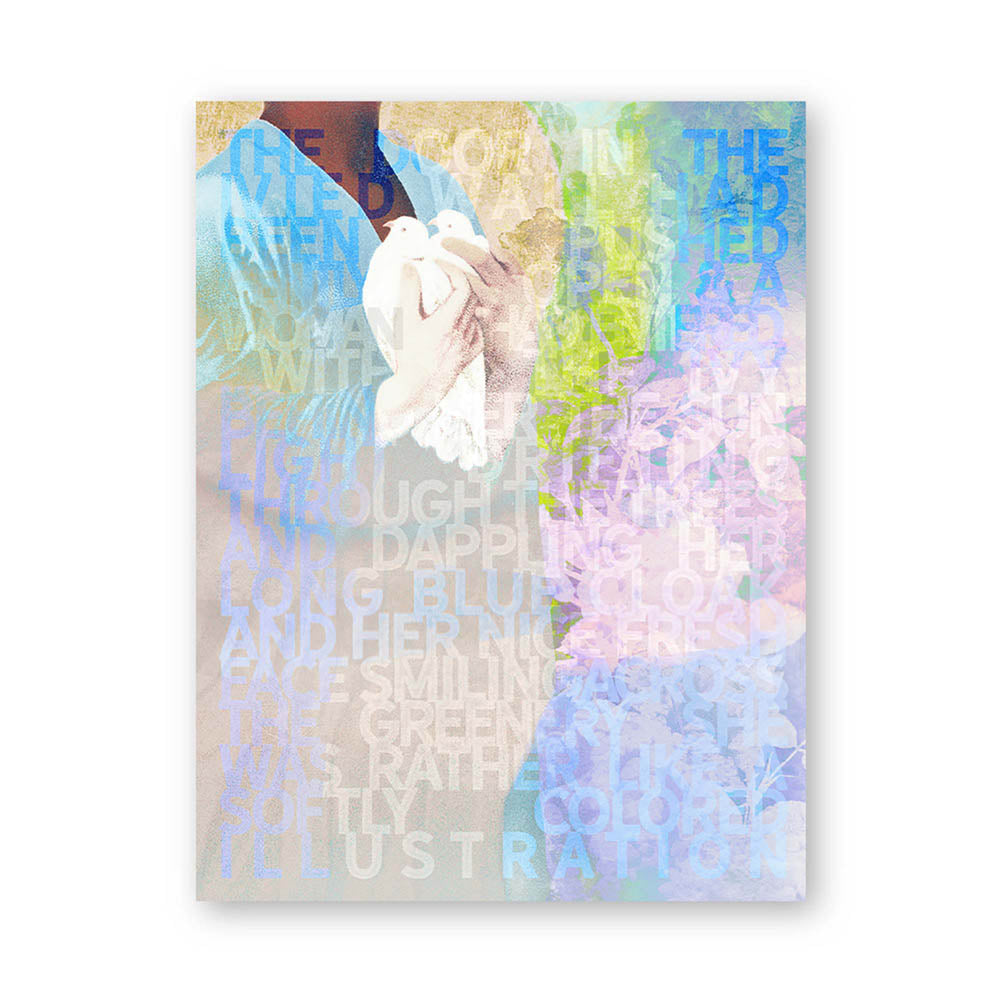

Her piece, Glimmer of Hope in a Quite Dead Garden depicts the secret garden before its revival. Yet it is far from one-note. The light blue backdrop suggests awaiting growth. Keen-eyed viewers will also notice oversize pages of the book itself varnished into the background, looking so at one with the painting they seem almost organic. “Our world today consists of so much media and information,” Julia says. “For me, that’s the beauty of our days, combining absolutely non-compatible materials and making sense out of all of them.”

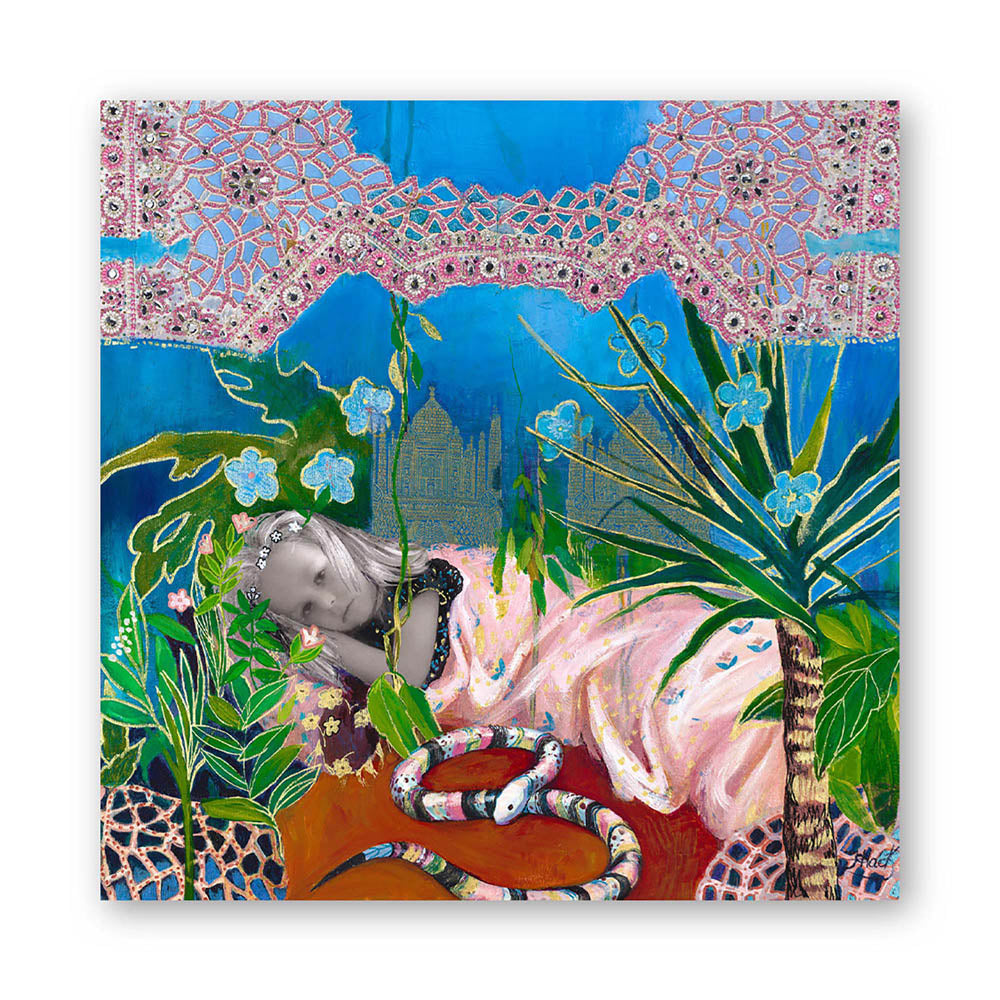

Similarly, Julia’s piece Never Alone uses mixed media to convey the depth of Mary’s solitude in the opening of The Secret Garden

While the painted background is vibrant and colorful, Mary is portrayed as a photograph of a stoic little girl in black and white. Above her hangs authentic Indian textiles, an homage to Mary’s upbringing. “We were talking about India and this feeling when Mary wakes up all alone in this house. I thought about those beautiful intricate embroideries and tapestries, and still a sense of loneliness. There are all of these beautiful things and you’re still all alone in the world. These things stuck out to me and so I decided to use original materials. I found fabrics that were hand-embroidered in India,” Julia says.

“For me, it’s bringing together digital media and materials that were created in historical, traditional ways. It’s combining and uniting everything together, how in spite of all the differences on the surface we all belong together.” While the artwork itself speaks to Mary’s loneliness, its message is centered around what unites us: the intensity of human emotion, and the vulnerability that comes with sharing those emotions.

From concrete to textiles, these creative choices embody the immense love Maggie and Julia pour into their work. This love allows them to create resonant pieces through which viewers can connect with the emotional state depicted, while also bettering the mental health of the maker. In this duality, we find the magic of artistic expression: something beyond words that creates as it is created.

Thank you to Maggie and Julia! To hear our conversation in full, listen to Art Talk on Spotify.