If your childhood was spent traversing rabbit holes, negotiating with hookah-smoking caterpillars, and attending mad tea parties, specific imagery likely comes to mind when you think of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and its sequel, Through the Looking-Glass.

Lewis Carroll’s children’s classic stole the hearts of readers with its vibrant and nonsensical world and the plucky heroine at its center. Still, when it comes to the imagery that defines these stories and the fierce grip they had on our imaginations, it is not solely Carroll who is responsible. John Tenniel was the artist and illustrator behind both Wonderland and Looking-Glass, and it is partially due to his whimsical and inventive illustrations that these stories remain so entrenched in the public imagination.

Tenniel was born in the Bayswater neighborhood of London in 1820. He was known as an introverted boy, preferring to spend his days sketching and drawing rather than gallivanting about with friends. His mother was a professional dancer and his father was a fencing instructor—from an early age, he learned to capture the intricacies of movement and energy in his drawings.

As a teenager, Tenniel became a student of The Royal Academy of Art, but he didn’t agree with the school’s teaching methods. At the Royal Academy, Tenniel was educated by pre-Raphaelite artists who taught that the only way to truly create art was to draw from life, making detailed studies of models. Tenniel, however, preferred to draw from memory, relying on his imagination to inform his artwork.

Carroll—who in addition to writing children’s books was a math professor at Oxford—would later say, “Mr. Tenniel is the only artist who has drawn for me who has resolutely refused to use a model and declared he no more needed one than I should need a multiplication table to work a mathematical problem.”

By the time Tenniel was 16, he had dropped out of the Royal Academy. The rest of his artistic education was entirely self-taught.

In 1836, Tenniel sent his first painting to an exhibition hosted by the Society of British Artists, where it was accepted. This was an enormous accomplishment for such a young artist, and it must have seemed that his artistic future was guaranteed.

One day in 1840, when he was only 20 years old, Tenniel was struck in the eye while fencing with his father. Initially, he showed no signs of pain, so much so that his father didn’t even realize he had hit his son with his rapier. However, Tenniel’s sight quickly deteriorated until he was completely blind in his right eye.

For a less determined artist, this may have been a career-ending accident, but Tenniel was not discouraged. He kept drawing and painting until he was once again confident in his skills. In 1845, he contributed a sixteen-foot-long cartoon to a design competition for a new mural that would decorate the Palace of Westminster. His cartoon was selected and he won £100 and a commission for a fresco in the Hall of Poets within the House of Lords.

In 1850 at the age of 30, he was invited to become a cartoonist at the popular political satire magazine Punch. Over time, Tenniel became Punch’s principal cartoonist, taking over their weekly political segment, the “big cut.” His most famous cartoon, “Dropping the Pilot,” came out in 1890 and mocked the resignation of the German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, showing Bismarck stepping off a ship while the German emperor Wilhelm II watches from above deck.

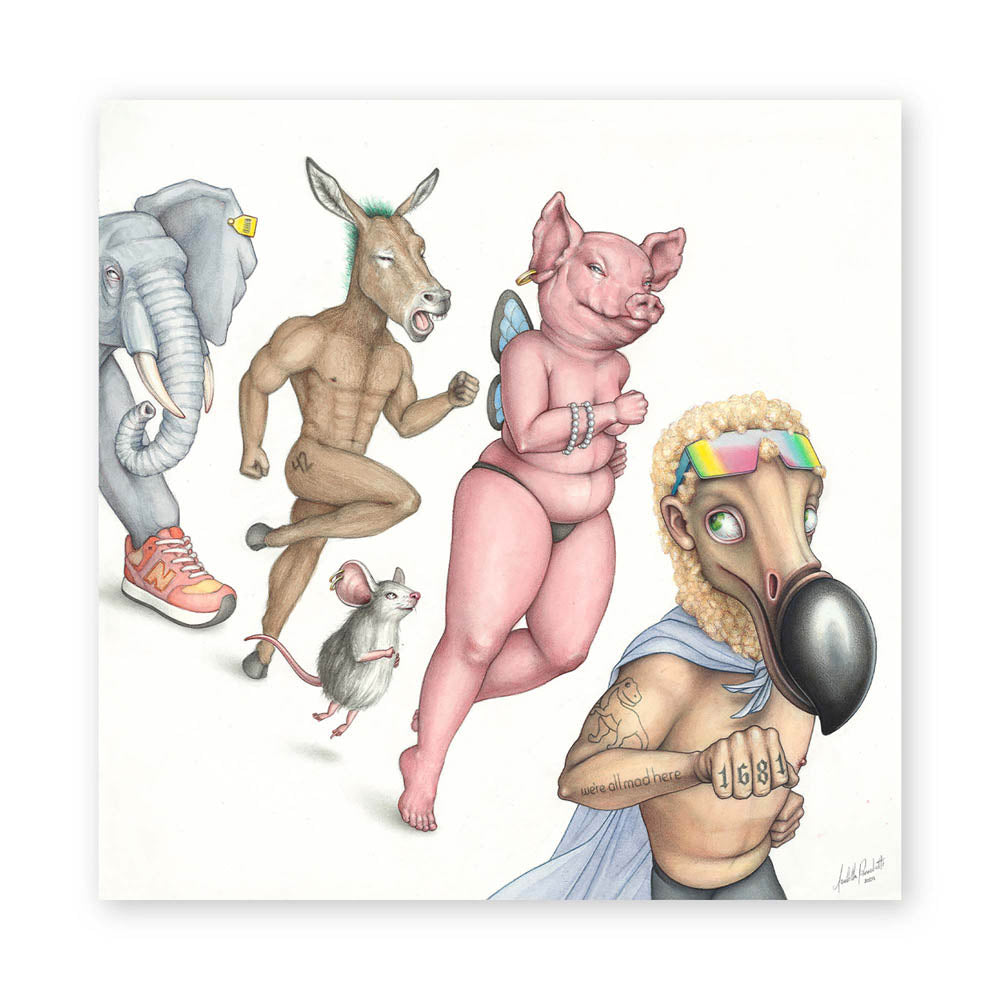

Tenniel’s style was particularly well suited to satire. His work was detailed and grounded enough that he could draw recognizable political figures while often giving them exaggerated features or placing them in nonsensical situations. His perfect blend of grounded realism and playful surrealism would come in handy when he began working on the illustrations for Wonderland.

Aside from his work in Punch, Carroll had seen Tenniel’s illustrations in an edition of Aesop’s Fables. He admired the theatrical quality of Tenniel’s work and his whimsical animal drawings. But Carroll himself had a passion for drawing and a highly particular vision for what he wanted. Of the original 42 illustrations Tenniel gave him of Wonderland’s characters, Carroll rejected all but one of Humpty Dumpty.

To create the stories’ iconic characters, Tenniel employed a style of crosshatching that gave the illustrations an illusion of depth and an added complexity. Once the illustration had been approved, Tenniel drew it on wooden blocks that were carved by engravers. From these wooden blocks, copper-plated lead blocks were electrotyped for printing.

While both men admired one another and valued each other’s opinions, they were both perfectionists who often struggled to see eye to eye. Their working relationship could be quite tense, with Carroll giving Tenniel multiple rounds of extensive edits.

Yet Tenniel was not entirely without blame. Upon seeing the first printing of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, he declared it “altogether unacceptable,” and insisted Carroll recall the 2,000-copy print run. Carroll went ahead with the recall, despite the fact that it came at a great financial cost and meant that Wonderland’s release would be delayed.

Carroll returned to Tenniel to do the illustrations for Looking-Glass in 1868. Tenniel initially refused but eventually agreed to work on the project. During this period, however, his and Carroll’s relationship completely deteriorated. After completing Looking-Glass, Tenniel refused to do any more illustration projects. Years later, in the late 1880s, he even went so far as to write to the illustrator Harry Furniss to dissuade him from working on Carroll’s children’s book Sylvie and Bruno. “Lewis Carroll is impossible,” Tenniel said. “I’ll give you a week, old chap, you will never put up with that fellow a day longer.”

While Tenniel appreciated the fame that came out of working on the Alice stories, he was happy to live in quiet obscurity and relative isolation. As a young man, he had been married for two years before his wife passed, and never remarried, preferring to be alone.

In 1893, he became the first-ever cartoonist to be knighted for his service in the arts, and by the time he retired from Punch in 1901, he had drawn over 2,000 cartoons for the magazine and was a defining voice of nineteenth-century satirical commentary.

He continued to draw and paint watercolors until old age caused him to lose sight in his left eye, making him completely blind. He passed away in 1914 at the impressive age of 93.

Tenniel led an inspiring and widely varied artistic career for over 50 years, creating high-brow artistic work and humorous comics that anyone could enjoy. Perhaps most impactfully, he brought to life the wild and wonderful world of Lewis Carroll’s daydreams, creating the colors, shapes, and contours of the Wonderland we have all come to know and love.

To learn more about John Tenniel, read…

“John Tenniel–an Introduction,” Victoria & Albert Museum, May 21st 2022.