On what would have been Jane Austen’s 250th birthday this past December, Janeites from near and far donned their bonnets, flats, and muslin gowns, flocking to the English countryside to revel in the legacy of one of literature’s most beloved darlings. I was not there, but I can imagine it: women in head-to-toe lace, carrying pale blue parasols in one hand and iPhones in the other. Whether self-described Janeites, Pemberley pilgrims, or Mr. Darcy daydreamers, there's one thing they would unanimously profess to Jane: "You must allow me to tell you how ardently I admire and love you."

But beneath this jubilant portrait of remembrance lies a truth that must be considered: our dear Jane—both the literary virtuoso herself and all that she represents—is indivisible from our longing to define what she was or wasn’t, to fill in the gaps of her biography that we can’t bear to face.

Jane Austen. A quiet spinster. Yes and a sharp-witted satirist writing amidst the chaos of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars! A humor-loving queen of romantic comedy! Suffragist icon and feminist foremother! But really, her message is romance and love, happy endings, loving for love, and maybe for marriage too.. and a little money. The choices women face. Could her witty protagonist be queer? Chick-lit, then wait, she wasn't chick-lit. Or was she? Let’s get back to politics, she was a progressive radical! No, she was tradwife-approved... and right to the start again.

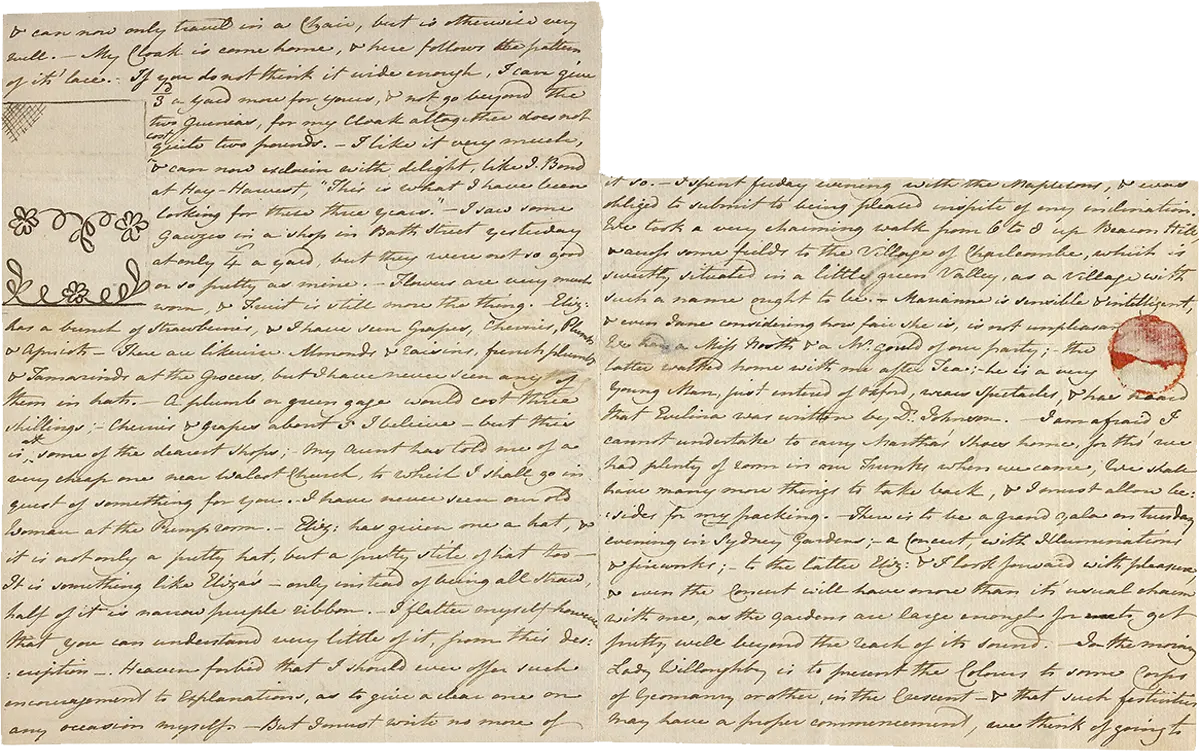

Austen’s sister and confidante Cassandra posthumously destroyed thousands of Jane’s letters, then snipped and trimmed others, effectively erasing the real Jane. As Helena Kelly, author of Jane Austen, The Secret Radical, notes, “there are so many gaps, so many silences, so much that has been left vague, or imprecise, or reported at second or third hand.” Jane is as much myth as she is truth, the facts of her life merely the pebbles on a river bed, the direction and movement of its water ours for the shaping.

Not unlike the snap judgments the women of Pride and Prejudice make upon receiving letters, we still impress our beliefs on everything we read. We misinterpret the tone of our husband’s text. We screenshot messages from Hinge matches. We forward, quickly, to the “safe space” group-chat for our friends to dissect and unpack. I think he means this. No, he meant that! Until we land either back where we began, or, with willful blindness, project our desires upon the suitors’ words.

How we read Jane is how we read ourselves: flawed, imperfect, evolving, and full of contradiction. Like love, her biography has many plausible definitions and bends to fit our cultural moment. And today, the culture is reconsidering the very foundation of hetero partnership in society—as evidenced by the slew of essays in recent months detailing women’s exhaustion with men. (TLDR: Having a boyfriend is embarrassing now and women’s expectations of male suitors are simply not being met).

Early Austen fans focused more on her witty voice and social satire than her love advice; it wasn’t until the Austenmania media craze of the late twentieth century that she became firmly solidified as our glorified love guru from centuries past. Ever since, we’ve desperately sought truth in Austen about love—how, who, and when to love. What it means to be single, whether our dating fatigue is valid and if Regency-era suitors were as self-centered and emotionally unavailable as they are today. We prescribe our heterofatalist views of romance upon her and our sudden enlightenment that we should “decenter” men, and maybe even reconsider our sexuality, twisting Lizzy’s scorn for Mr. Collins into a queer manifesto: "You could not make me happy, and I am convinced that I am the last woman in the world who would make you so."

We're right that Austen demands more than blind-eyed lovers or storybook daydreamers—her characters do, after all. But by fixating on what type of love Austen prescribes, we miss the core tenet of Pride and Prejudice: that what others believe to be true doesn't capture our own individual reality or lived experience. That each lovergirl has different compromises she is willing to make when it comes to matters of the heart. That every unmarried “spinster” is full of self love. Lizzy herself sums it up perfectly in that fabulous scene toward the end of Pride and Prejudice when she so “obstinately” tramples over Lady Catherine’s contempt: "I am only resolved to act in that manner, which will, in my own opinion, constitute my happiness, without reference to you."

Austen shows us no character is wholly right, no facade is what it seems, and that language can repair us as often as it fails us. Neither Darcy nor Elizabeth’s first impressions of each other turn out to be accurate; their perspectives are as wrong as the gossip of the English “society” is clouded by bias. Lizzy wants love and she deserves it, but she doesn’t dilute herself by groupthink. She isn’t influenced by Charlotte’s pragmatism or her mother’s flawed marriage or Jane’s too lenient forgiveness of the Bingleys. She isn’t uploading her situation into AI to decode how best to act. Instead, she learns about the love she desires by transitioning from looking outward to looking inward. Re-reading Darcy’s letter, she has her major reckoning, reflecting on her own wrongs and confessing, “Till this moment I never knew myself.” Her truth comes from within, even as Austen problemetizes our frantic search for romantic certainties. As a student of Austen put it, “Pride and Prejudice also reveals that sometimes, the search for ontological truth and the search for romantic love are one and the same.”

What I want to put forth by all this musing is this: we love Austen because her heroines mirror our own romantic longings, however messy they are. We can spend our whole lives dissecting her caustic language and witty asides to justify our own cultural narratives but Austen’s wide cast of characters muddy any certainty about what Austen herself believed. The same can be said for current dating discourse. Rather than latching onto any one idea of what Austen teaches us about love—what it feels like, looks like, its contours and its silhouetted shapes—we should see her as one part of centuries-old discourse, and decide where we fit into that story.

So if you’re seeking love and answers about how to find it, I’m not saying you shouldn’t turn to Austen’s fiction for elusive truths about your heart’s yearnings. We all deserve to know ourselves and find matches for our unrequited love—we just might not find them in her writing. Those answers come from within.

We’re shaping up the Pride & Prejudice Art Novel, launching this fall, to be a kindred spirit to Jane—one that has many possible meanings, lovers, and happy endings. Join our email list for first access to its limited release shipping fall 2026.