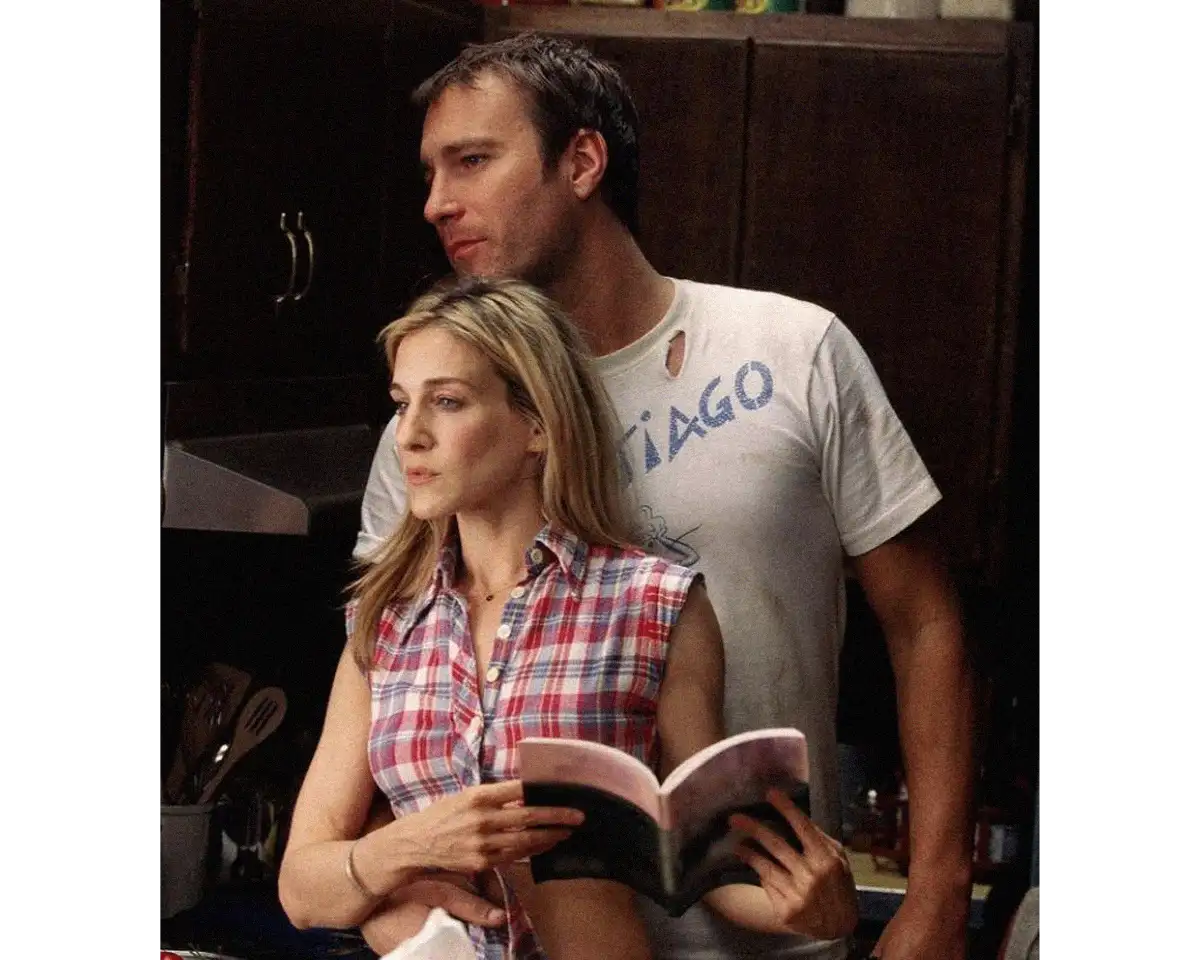

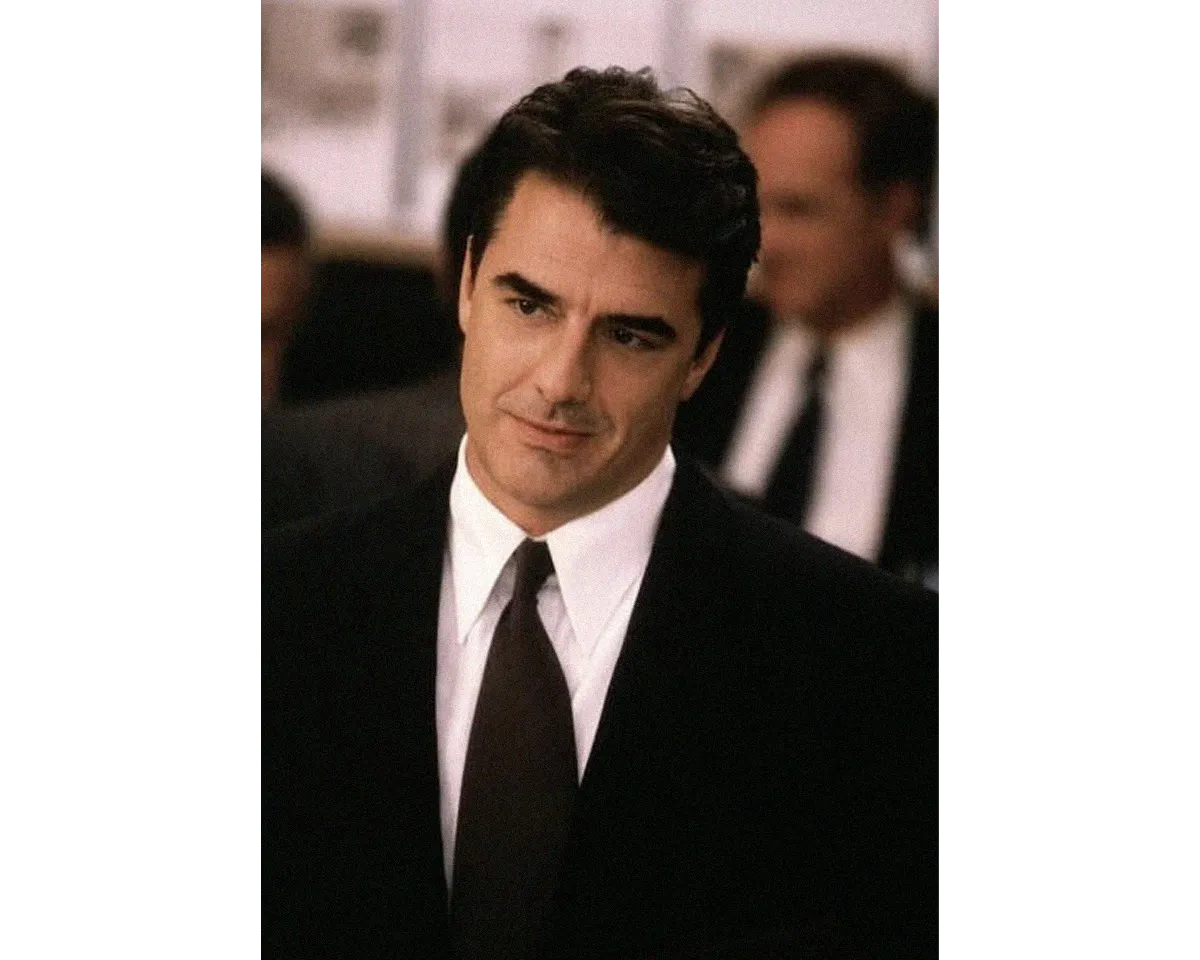

What is it about a guy who doesn’t know what he wants? In Sex and the City, Carrie’s enchantment with Big and his confusing gestures is no exception. Big is notorious for his “push-pull” style of affection—he shows affection when it’s inappropriate, and he retracts the moment Carrie surrenders to it. In the episode “Easy Come, Easy Go,” Big teases Carrie when he claims he’s leaving his wife. He rescinds the offer, but by the end of the episode, he finds Carrie at the hotel where she is writing, while her boyfriend, Aidan, fixes the floors in her apartment. It is only when she makes it clear that she no longer wants him that Big chooses to be vulnerable with her, admitting that he loves her, which causes them both to cheat. The episode ends with both Carrie and the audience confused as to what’s next. If this is painful to watch, it’s because it’s relatable. What is it about an entropic love affair that feels so good? It’s an old tale, really. A pertinent example comes from the famous Elizabethan, Metaphysical poet, John Donne.

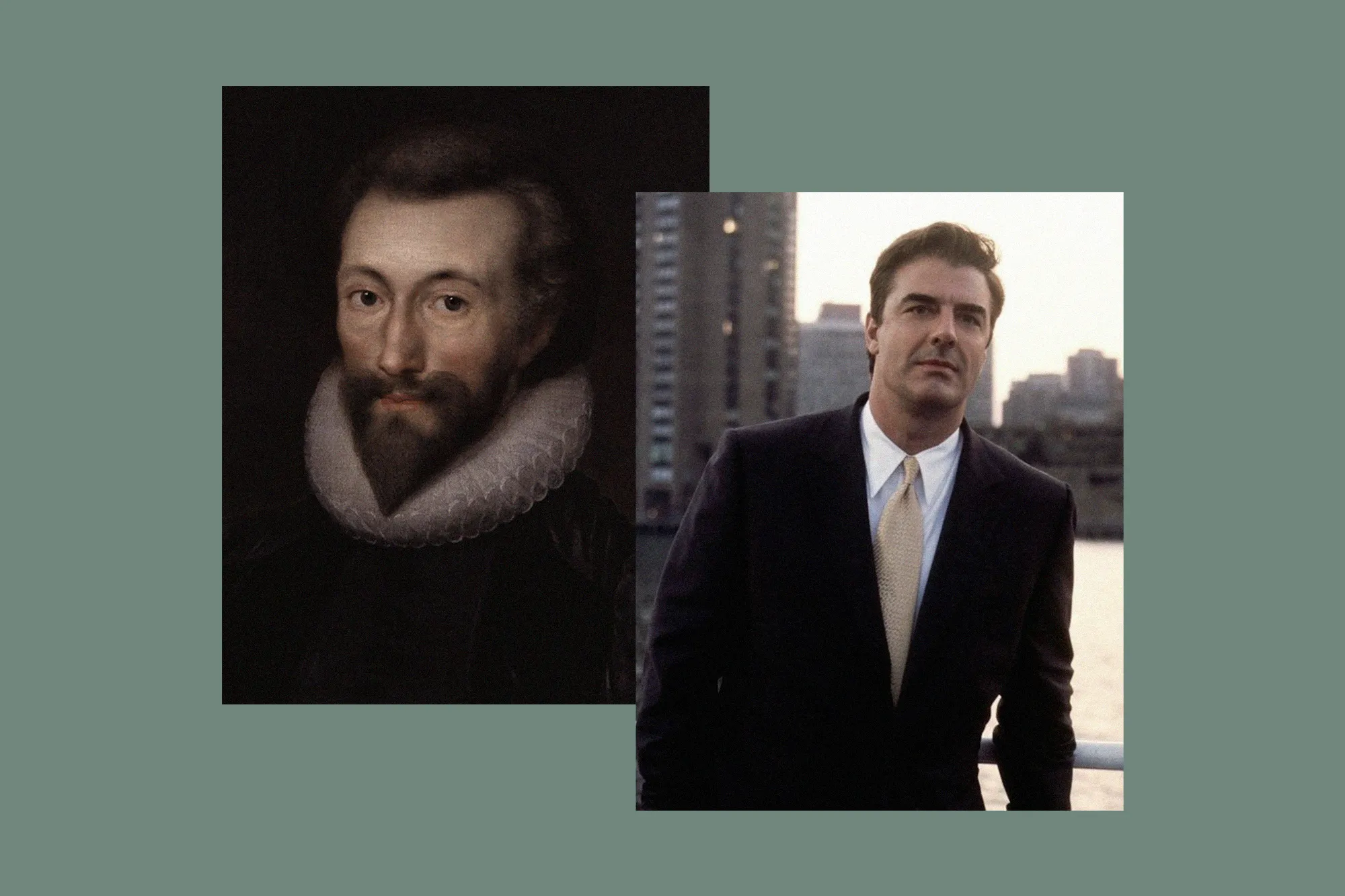

John Donne was born in London in 1572 into a prominent Roman Catholic family. He studied at Oxford and Cambridge, but he did not receive his degree because he refused to sign a requisite oath of allegiance to the Protestant crown. Before being charmed by his loyalty, he abandoned Catholicism in the mid 1590s for Protestantism, later becoming a celebrity preacher as the Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral. He is one of the most famous Metaphysical poets—a term coined by the writer Samuel Johnson for a group of poets whose works were known for being highly intellectualized, using inventive conceits, and placing an emphasis on spoken rather than lyrical verse. Donne also wrote some of the sauciest verses in English poetry.

Among Donne’s poems, “Elegy XVI: The Expostulation” most closely resembles this scandalous moment between Carrie and Big. It’s a long poem about a jealous man protesting his mistress’ new lover. I’m going to break up and summarize most of the poem, and then I’ll explain how it relates to Big and Carrie.

“To make the doubt cleare, that no woman’s true,

Was it my fate to prove it strong in you?” (II. 1-2).

Immediately, the tone and message of the poem is set: Donne, like Big, is “salty” about his mistress’ new lover. Naturally, he blames her for being false to him, conveniently labeling himself as unlucky.

“And must she needs be false because she’s fair?

Is it your beauties marke, or of your youth,

Or your perfection, not to study truth?

Or thinke you heaven is deafe, or hath no eyes?

Or those it hath, smile at your perjuries?” (II. 4-8).

Donne presents a list of witty conceits. Still playing on his mistress’ falsehood, he questions whether all beautiful women are predestined liars, or if she knows she can get away with lying because she’s beautiful. Donne comforts himself by supposing that she believes she can outwit the law and order of God with her charm, too; if it could happen to God, it could happen to anyone.

“Are vowes so cheape with women, or the matter

Whereof they are made, that they are writ in water,

And blowne away with wind? Or doth their breath

(Both hot and cold at once) make life and death?

Who could have thought so many accents sweet

Form’d into words, so may sighs should meete

As from our hearts, so many oaths, and tears

Sprinkled among, (all sweeten'd by our feares,

And the divine impression of stolne kisses,

That seal’d the rest) should now prove empty blisses?

Did you draw bonds to forfet? signe to breake?

Or must we reade you quite from what you speake,

And finde the truth out the wrong way? or must

Hee first desire you false, would wish you just?” (II. 9-22).

The unraveling of emotions here is quite interesting. Still angry, Donne claims that her vows are lies, and her inconstant love is cruel. The last point makes him vulnerable—were their passionate kisses meaningless, or worse, one-sided?

His sadness returns to anger and confusion. In this state, he poses intriguing questions about the nature of written versus spoken words: If vows can be broken whether they are recited or written, in which one can the truth be more easily detected? As a result, we see the unraveling of a man who no longer trusts himself, questioning his own motives of whether he admired her beauty before even considering her character.

“O I profane, though most of women be

This kinde of beast, my thought shall except thee;

My dearest love, though froward jealousy

With circumstance might urge thy’inconstancie,

Sooner I’ll thinke the Sunne will cease to cheare

The teeming earth, and that forget to beare,

Sooner that rivers will runne back, or Thames

With ribs of Ice in June will bind his streamers,

Or Nature, by whose strength the world endures,

Would change her course, before you alter yours.” (II. 23-32).

So, she cheated, but he doesn’t blame her. Instead, he blames himself because he doesn’t trust himself. It can’t be her fault because it was his own jealousy that spurred her on. Besides, nature will do the impossible before his mistress would act unfaithful towards him, right?

It becomes easier to find excuses than to face the truth.

“But O that treacherous breast to whom weake you

Did drift our Counsells, and wee both may rue,

Having his falsehood found too late, 'twas hee

That made me cast you guilty, and you me,

Whilst he, black wretch, betray’d each simple word

Wee spake, unto the cunning of a third.” (II. 33-38).

Lo and behold! Our Aidan figure enters the picture. Donne shifts the blame from himself to this man for infiltrating and ruining his fidelis relationship. In the following portion of the poem, Donne curses the man, but I’ve omitted this. Although it is fun to read Donne viscerally describe cruel punishments, this final portion is more to the point:

“Now have I curst, let us our love revive;

In mee the flame was never more alive;

I could beginne againe to court and praise,

And in that pleasure lengthen the short dayes

Of my lifes lease; like Painters that do take (win you back

Delight, not in made worke, but whiles they make;

I could renew those times, when first I saw

Love in your eyes, that gave my tongue the law

To like what you lik’d…

Love was as subtilly catch'd, as a disease;

But being got it is a treasure sweet,

Which to defend is harder than to get:

And ought not be prophan’d on either part,

For though’tis got by chance, ’tis kept by art.” (II. 53-61, 66-70).

Now that the other guy has been cursed, Donne hopes they can go back to loving. In fact, he wants her more than ever. A player like Donne is toxic—for him, the real fun is in the pursuit. He reminisces about the past: their first time having sex, exploring one another, and wondering if it could ever be like that again—before that punk came along and tainted their love. Yeah, Donne was betrayed, but for her, he’s willing to be flattered.

He goes as far as to say that their love is a disease so sweet that he hopes to never recover. Neither should they ever disrespect the sanctity of their shared disease, they were lucky to have contracted it in the first place, and they must work to retain it. This is by far the most confusing simile in the poem.

But comparing love to a disease he wishes to keep is a trademark of Donne’s ingenious ability to summarize a long, complicated poem about conflicting emotions into a few lines. Though this poem is an expostulation cursing another man for violating his relationship, deep down Donne knows that he and his lover willfully violate themselves by engaging in this toxic behavior.

Referring back to Sex and the City, Big grows jealous of Carrie’s new relationship despite being married himself. However, their love is like a disease that lasts the duration of the show, and it is kept active by Big’s art of “pushing and pulling,” as well as Carrie’s submission to her own emotions. In “Elegy XVI: The Expostulation,” Donne blames the woman for being false, grows angry at her and her other lover, curses him, but ultimately he cannot resist her, continuing to fight for her. Is the sexual intrigue of this poem Donne’s vulnerability, or his toxicity? Is Donne’s art of relating emotions all too familiar for women who have been involved with emotionally distant men his way of driving his lady closer? It appears that the entice of confusion is not gendered, but it is the language of intense lust.