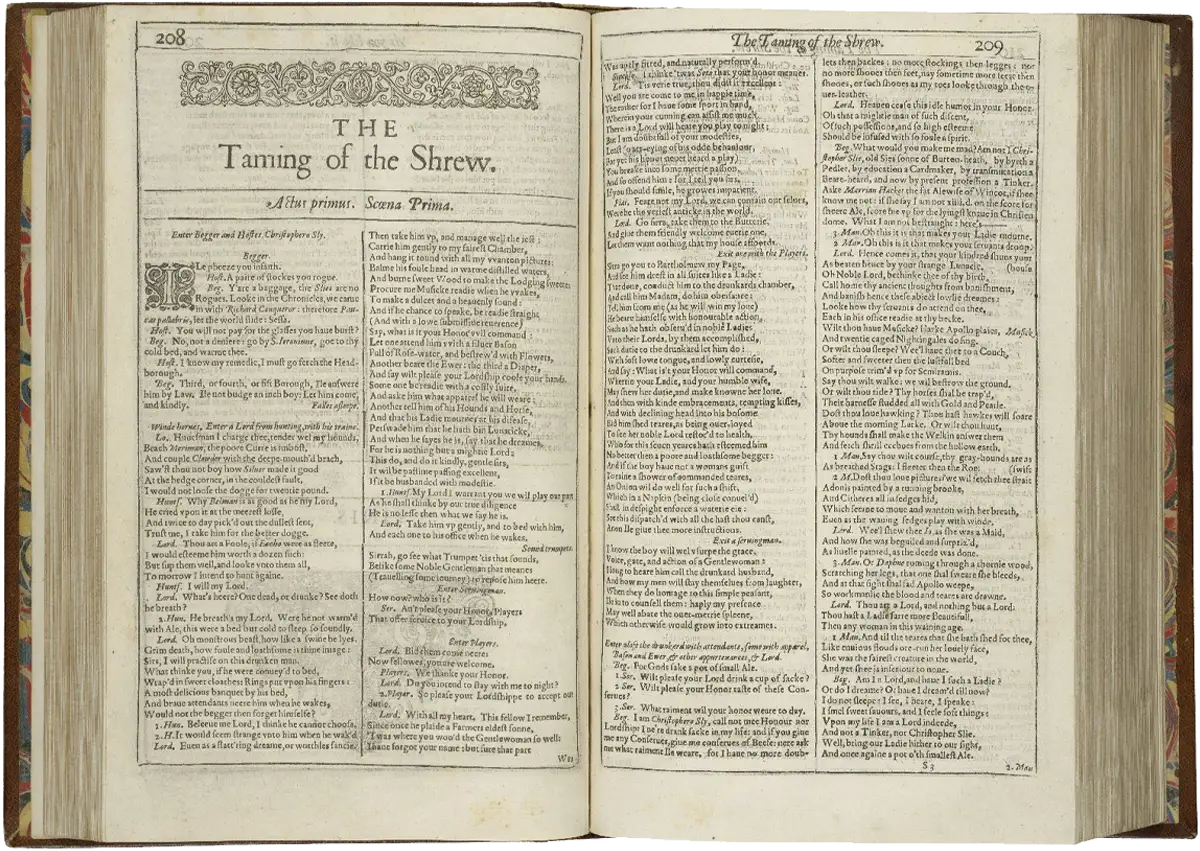

Katherine Minola from William Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew (c. 1590-1592) has been called many things, and sympathetic is usually not one of them. The hardened, no-nonsense female lead of this controversial play is derided, mocked, and eventually abused by the male characters, a treatment that, confusingly, is intended to be comedic. Katherine’s brazen nature is, as implied by the title and text, likened to that of a wild animal, whose spirit must be broken until she submits to domesticity. The Taming of the Shrew is not looked on as fondly as Shakespeare’s other works, and yet, Katherine’s dynamic with her coarse, arrogant love interest, Petruchio, has been retold again and again to great success. How can this be?

The Questioning of the Bard

Patriarchal power dynamics are a common thread in many of Shakespeare’s plays, given the social politics of the Elizabethan era in which they were written. In another comedy play, Much Ado About Nothing (c. 1598-1599), the similarly tough Beatrice is referred to as a “harpy” by Benedick. And yet, while these two love interests may trade barbs and butt heads more than once as they humorously stumble into romance, the kind of abuse that Katherine faces at the hands of Petruchio is notably absent. The Taming of the Shrew is decidedly harsher than any of the other comedies in Shakespeare’s canon, and even Elizabethan audiences weren’t always keen on its messaging.

Though the exact date of its completion is unknown, playwright John Fletcher is believed to have penned his sequel, The Woman’s Prize, or The Tamer Tamed, during Shakespeare’s lifetime. This comedy has Petruchio “tamed” by his second wife, forcing him to experience the same cruelty he had once bestowed upon Katherine. The text is essentially a revenge fanfiction, and its existence refutes the idea that The Taming of the Shrew reflected the broad public opinion of the time. “Justice for Katherine” seems to be the underlying emotion in the ensuing years of critical analysis and adaptation, yet, despite Fletcher’s first attempt, it was not through violence that her character was finally granted deliverance.

From the Antiquated Page to the Reformed Screen

What happens when modern directors take a famously misogynistic story and inject feminism into it? The Taming of the Shrew has been reimagined many times over the past hundred years, but two of these adaptations stand above the rest in terms of popularity, message, and character: 1999’s 10 Things I Hate About You and the 2022 second season of Bridgerton.

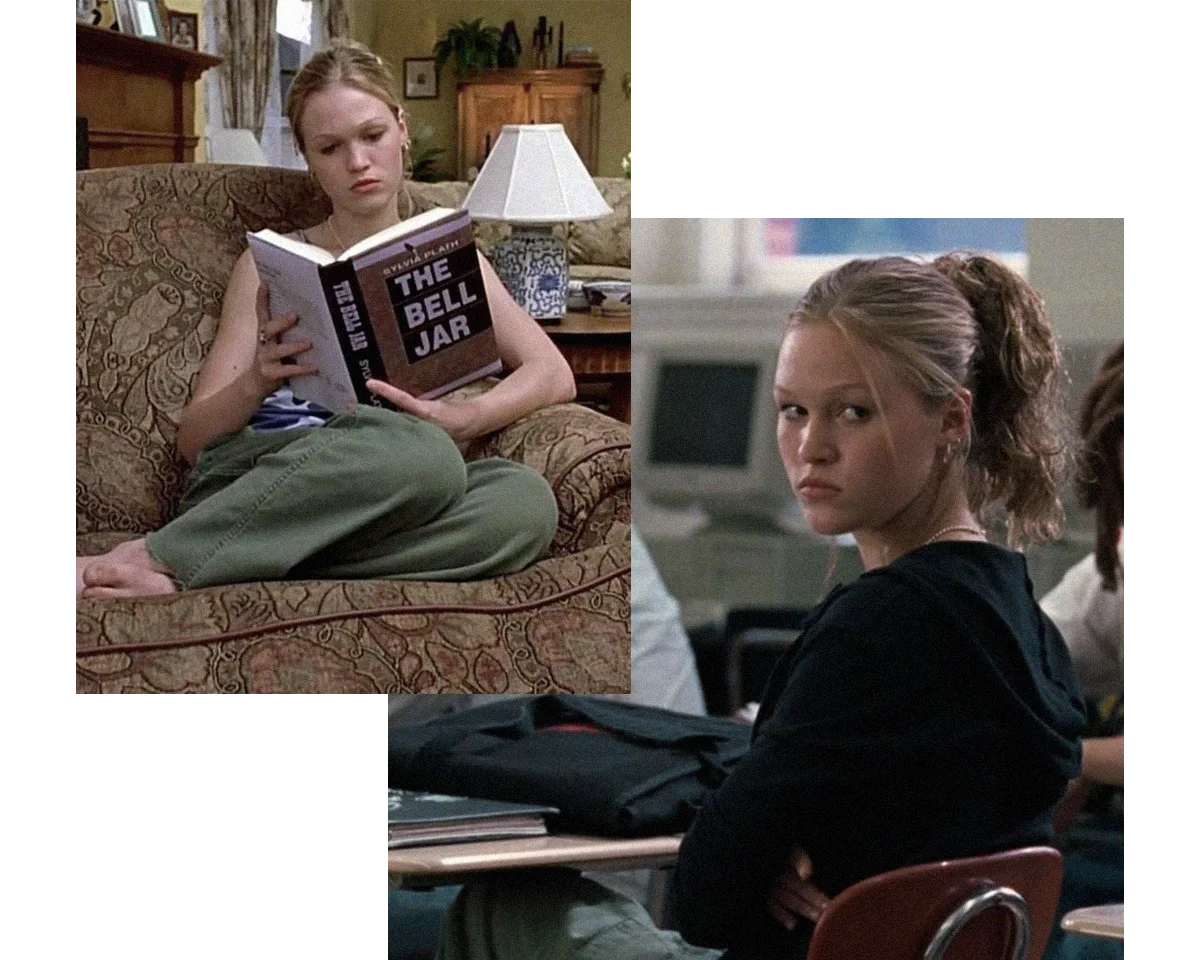

10 Things I Hate About You was released during a cultural craze in the ‘90s and early 2000s, when Shakespeare’s plays were transported into a high school setting. This decision seems odd for a piece as harsh as The Taming of the Shrew, but the teenage angst actually improves the script by justifying the ridiculousness of the characters’ actions, which, in turn, successfully brings this production into the realm of comedy.

The Katherine character in this production, Kat Stratford, coyly refers to herself as “tempestuous” near the start of the film. Indeed, she is quick to anger and seems to loathe the entirety of the student population, but as we get to know her on a deeper level, the audience realizes that this rough exterior is merely a protective mask. Kat lost her mother when she was a freshman in high school, and during this emotionally vulnerable time, she was pressured by her showboating boyfriend, Joey, to lose her virginity to him. When she refused to have sex with him again, Joey dumped her and smeared her reputation as a, well…shrew…to their peers.

This added element of Kat’s backstory is only a piece of how this film improves upon its source material. The redressing of Petruchio—known here as Patrick Verona—is also a defining factor. Patrick is also a hotheaded outsider like Kat, and while extorting money from his classmates in order to get Kat to go out with him is merely a game to Patrick at the beginning, the more time he spends with her, the more he genuinely starts to fall in love with her. Kyle Kallgren put it best in his 2014 video essay on 10 Things I Hate About You, when he said, “Kat is not tamed, she is simply loved." Patrick is not abusive to her as Petruchio was in The Taming of the Shrew, and the script does not have Kat submit to him. She maintains her confident, defiant nature right up until the end credits, flipping the original Shakespearean ending on its head in favor of something more modern and more empowering. While Kat does soften toward the end of the film, it is not at the expense of her spirited nature; she does not have to become smaller and meeker in order to deserve love.

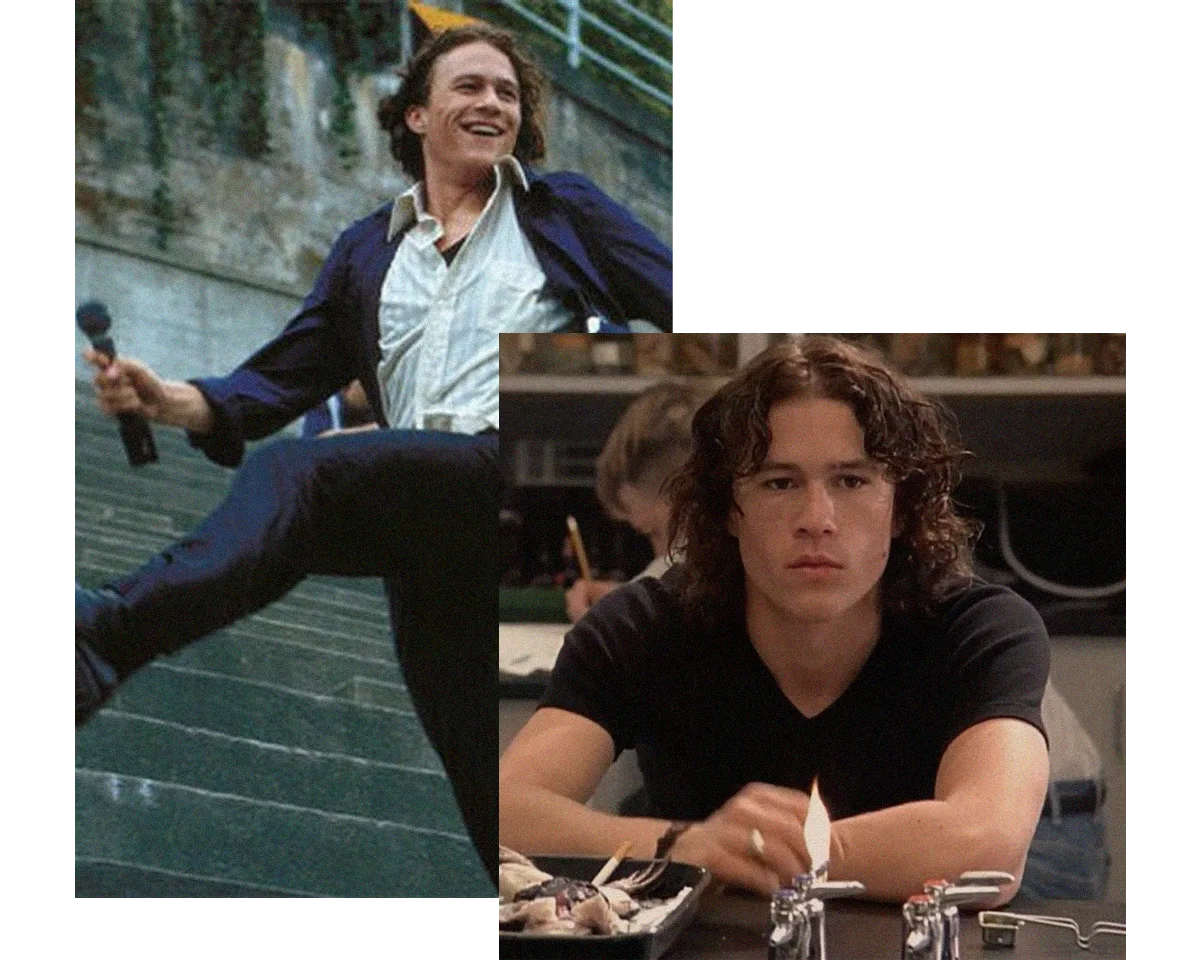

Netflix sensation Bridgerton has explored many classic romance tropes since it first premiered in 2020, and during its second season, the enemies-to-lovers plot has a familiar Katherine/Petruchio twist to it. When the arrogant Viscount Anthony Bridgerton is overheard referring to prospective brides like cattle for breeding by Miss Kate Sharma, she does not make her ire a secret. Kate is far bolder than any woman Anthony has ever known, and the vicious dressing down she gives him plants the seed of their bitter rivalry. Kate thwarts his attempts to court her younger, more amiable sister, Edwina, but as the two continue to clash, they find that the passion sizzling beneath their words might not be hatred at all.

While Anthony’s misogynistic view of marriage initially seems to align with Petruchio’s callousness in the original play, we eventually learn that Anthony is merely afraid of giving himself over to love. Anthony was only 18 years old when his father died, and the anguish and all-consuming depression his mother experienced afterward was more than Anthony could bear. His character arc over the season is about reclaiming the affectionate nature he once had in his youth, not just for the sake of his romance with Kate, but also for the sake of better caring for his family.

Kate is also revealed to have lost her father when she was young, but her story is less about a fear of love and more about the Eldest Daughter trope. In the wake of her father’s death, Kate took her family’s finances and future on her shoulders, sacrificing her happiness and dreams to prepare her sister for a suitable match. At 26 years old, Kate is considered a “spinster” by the Ton, saving her from the ridiculous pageantry of the marriage mart but not from its derision. Kate is reminded again and again that her time for romance has passed, and she shields herself from this pain by hiding behind layers of emotionally caustic armor.

Like Kat Stratford in 10 Things I Hate About You, Kate Sharma is never “tamed” by Anthony. Instead, the two learn to become more vulnerable with one another, discarding their defenses in favor of trust. Neither Kate nor Anthony is punished for their competitive natures or headstrong ferocity, but instead, these qualities take on a new light when being guided by love rather than acidity.

Modern reimaginings of The Taming of the Shrew owe their success to the treatment of the Katherine character. While the original script implies that Katherine’s abuse is both deserved and necessary, contemporary retreads instead ask the audience why she is so despised. Empathy is the driving force in these adaptations, allowing both Katherine and Petruchio to rise above the disparaging characterizations Shakespeare initially wrote for them. Perhaps Katherine was never really a “shrew” at all, only misunderstood by everyone around her.