Graffiti’s value to society has long been contested. As some see it, they’d rather not have their fences “vandalized” or their local store “defaced” by the hurried, unfinished tags of graffiti artists working in the night. A fair argument, given that graffiti, by definition, defies the law.

But proponents of graffiti challenge this thinking: what good is the law when it thrives on the incarceration of marginalized bodies, when it creates rules only to enforce them selectively? And if the law itself is unjust, what virtue is there in abiding by it?

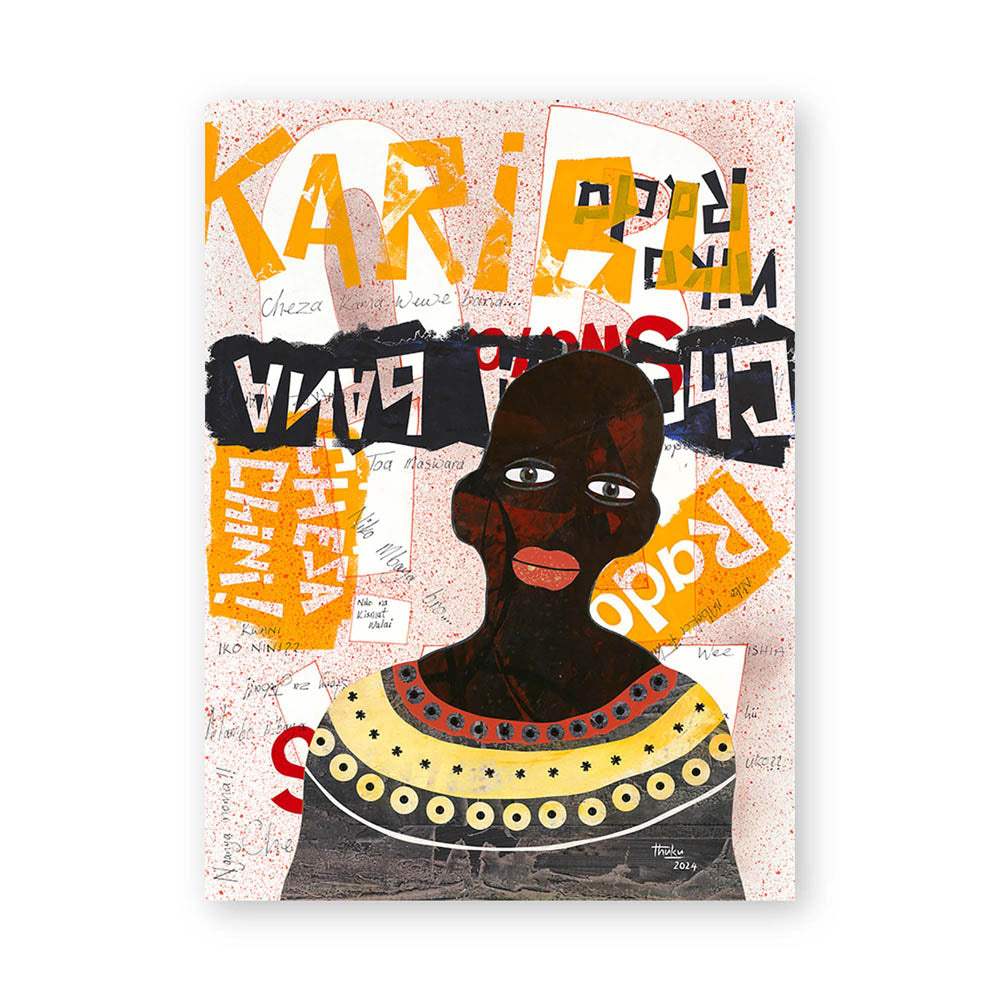

Is graffiti necessary or a nuisance? Art or an eyesore? These questions have fueled debates for generations, becoming more urgent and nuanced as graffiti gains legitimacy as a form of cultural expression. Like many avant-garde cultural movements that later enter into the mainstream, graffiti is born from a need to voice an idea or identity that the larger society ignores. Its power lies not just in its chaotic, transgressive strokes or the permanence of spray paint, but in its ability to reshape and reclaim public space.

“The very activity of producing culture has political meaning,” writes Media and Culture scholar Stephen Duncombe in an essay on cultural resistance. “The first act of politics is simply to act.” But cultural resistance can also have a less overtly political output, taking the form of a safe space or a “haven in a heartless world,” where people can express themselves and experiment outside the “limits and constraints of the dominant culture.” Graffiti, by Duncombe’s definition, is deeply intertwined with cultural resistance; to call graffiti vandalism is to overlook the fact that it is often within the very communities that are not only the most marginalized but the most targeted by racialized policing that the form of expression thrives.

This helps explain why many who create graffiti call themselves “writers,” seeing the act less as a visual art form and more as a form of self-expression. As Ismael Illescas put it, a scholar of Ethnic Studies who has researched the impact of graffiti on Los Angeles subcultures, “In a city where these youth are marginalized, ostracized, and invisibilized, graffiti is a way for them to become visible.” It functions as a cultural marker, a form of "illicit cartography," Illescas said, that can map the presence of subcultures and social histories.

Graffiti dates back to ancient Rome, but its modern form as a tool of resistance in America arose in Philadelphia and New York in the ’60s and ’70s. Darryl McCray, better known as Cornbread, is widely regarded as the father of modern graffiti, having found his voice as a writer while in a youth detention center. Craving his grandmother’s cornbread over the bland white bread they served, he began scrawling the comfort food on the center’s walls in an empowering act of dissent.

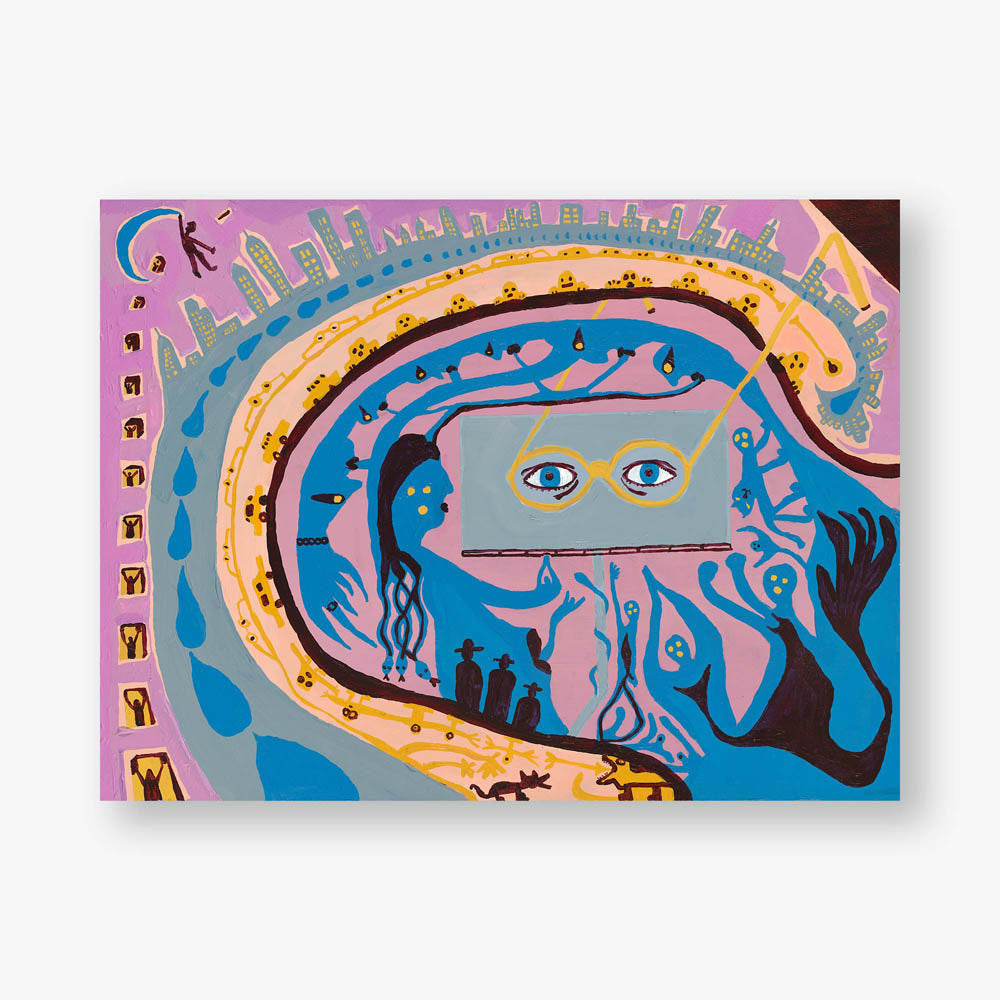

Meanwhile, in New York, amid a financial crisis, rising crime, and social unrest, graffiti flourished in Black and brown neighborhoods—especially in the South Bronx, East Harlem, Washington Heights, and Bushwick—as disempowered communities found a new mode of expression. City officials (and residents, particularly in wealthier neighborhoods) saw the surge of graffiti as a threat, declaring a “war on graffiti” in 1972. But for the youth participating in the movement, and a political movement it was, this was not vandalism but a “complex cultural phenomenon,” as early graffiti historian Herbert Kohl argued in 1969, a “form of expression” and an “art.”

Young New York “writers” sought exposure and volume, “bombing” subway cars across the five boroughs in an act no different from picketing in the streets: we deserve to be heard. Indeed, it was no coincidence that graffiti flourished during a time of mounting frustration for Blacks who continued to suffer from segregation and poor economic conditions. Journalists Dimitri Ehrlich and Gregor Ehrlich linked graffiti's rise directly to this community’s oppression, calling it an “artistic response to the public protests of the Black Power and civil-rights movements.”

Notably, the Black Panther Party saw the subversive, political power in using public space to communicate outside the racial boundaries of white culture. In the late ’60s and early ’70s, under the leadership of Emory Douglas, the Party’s Minister of Culture, images of resilience spread through hotbeds of Panther activity including South Compton in Los Angeles and Harlem in New York. Soon, the symbols, faces, and slogans of the Party were, in turn, absorbed into local street art, capturing the shared struggle at the heart of the Black Power Movement.

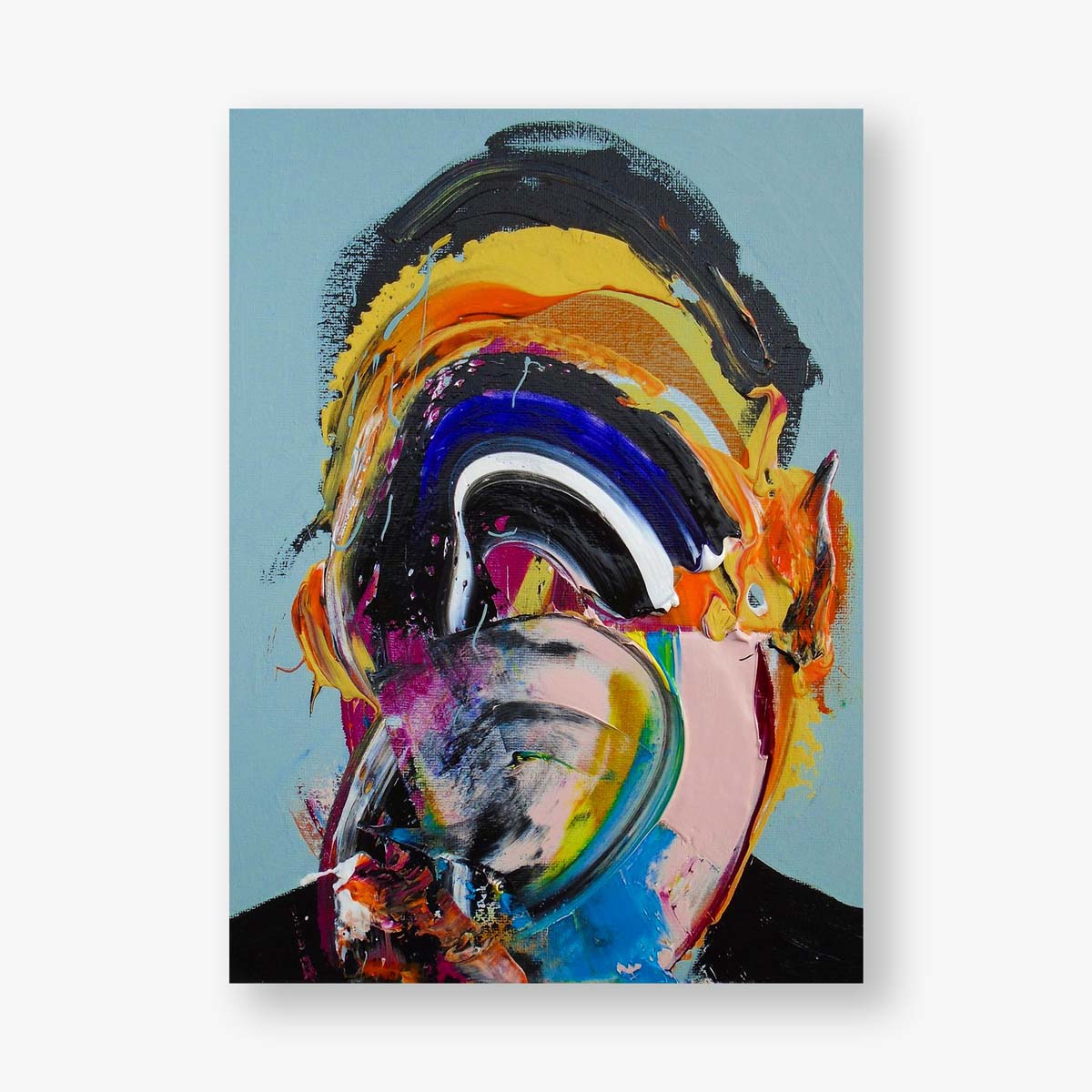

For Lee Quiñones, the now-renowned Puerto Rican painter and artist who grew up in the projects on the Lower East Side, the underground culture of spray painting subway cars offered him an escape, a community, and a sense of belonging. Introduced to the scene as early as 13, Quiñones soon became an early pioneer of large scale subway murals, infusing them with social and political commentary. “Being introduced to that scene, and the movement in the trains, was a sort of freedom” he recalled to Vanity Fair. “It was really, truly the Underground Railroad for me.”

Soon, the vibrant, unapologetic energy that Quiñones channeled into his work hit the gallery scene as New York’s art world began to recognize the artistic potential and expressiveness pulsing through this overlooked generation of emerging talent. A “DIY” underground art exhibition named “The Times Square Show” in 1980 featured Quiñones’ work alongside the work of his now legendary contemporaries including Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat. Showcasing the subversive work of artists who had either found their voice in graffiti or been deeply influenced by street art and urban culture, the show was an early effort to democratize the art world and bring urban art to the mainstream.

Today, while publicly sanctioned mural art projects have elevated graffiti to what we now call street art, the broader narrative around urban art remains divided between the community-driven murals and illicit, covertly-scrawled graffiti. While such a distinction is useful for law enforcement purposes, it overlooks the origins of graffiti as a form of cultural resistance that took generations of men and women like Cornbread—detained, yet determined—who refused to be seen as scapegoats for society’s broader issues.

Nowhere has graffiti’s power to reshape public space and rewrite history been more striking than in the 2020 community takeover of the Robert E. Lee monument in Richmond, Virginia. Once a towering symbol of the Confederacy, the statue and its surroundings were transformed by spray paint, basketball hoops, neighborhood cookouts, and even a community garden in the wake of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery’s murders. What was once a monument commemorating the oppression of Black bodies became a radical site of defiance—a revolution fueled by the people. As poet Les James expressed: "This right here is how we transform the silence / of a memorial dedicated to the perpetuation of violence / into a loud celebration of our perpetual defiance.”

Suggested Reading:

- Decorating Dissidence

- To what extent can graffiti and street art be considered a form of contentious politics?

- History of graffiti and street art: the 1960s and the 1970s

- The writing on the wall: exploring the cultural value of graffiti and street art

- Treasure or Trash: Graffiti’s Value in NYC Culture

- Graffiti in its Own Words