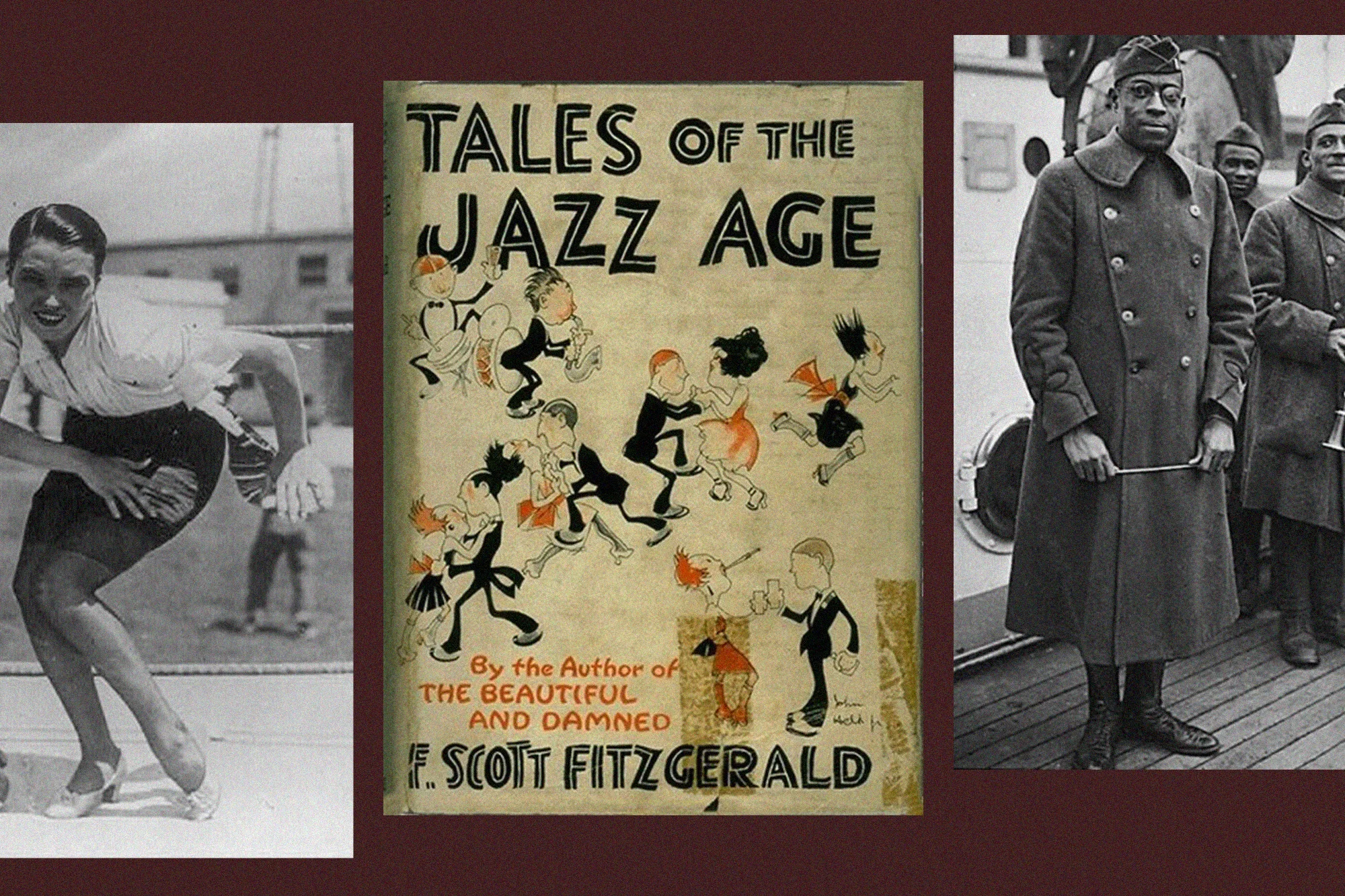

In 1972, the painter, poet, and literary critic John Berger famously wrote, “The way we see things is affected by what we know or what we believe.” Half a century later, in 2025, no one dictum seems to ring quite as true, especially in a culture straining under divisiveness, violence, and our stubborn conviction in our own rightness. This is where the power of art steps in, boldly, insistently, and with demanding expectations of us. Art may not save lives, but it can help us see beyond the narrow vantage point that shapes our perspective: by presenting alternative ways of seeing, artists help us recognize just how distorted our own perspectives may have become.

In curating an art collection tied to the centennial of The Great Gatsby, a novel that has since come to be known as the Great American Novel, no one piece of wisdom bubbled to the surface with quite as much force. This collection, my co-curator Maggie Lemak and I promptly realized, must center the rising importance of perspective in our contemporary cultural discourse. Scouting artists with local and global views, some childhood fans of Gatsby and others first time readers, we settled on a collective of 14 ambitious artists who were prompted with two questions: what does greatness mean to you, and what vivid glimpse of greatness does art offer in your life?

These questions generated creative ripples that spread beyond each artist’s personal life and through the pearly gates of Fitzgerald’s prose, helping them uncover the themes of illusion, deception, and longing that lie at the heart of this tragic and often misinterpreted story. As the Gatsby centennial ignited think pieces and deep dives into pop culture, these 14 artists created new work positing what it means to dream and uncover truth in America, and in this world, today.

Entitled “A Vivid Glimpse” (of greatness), the collection features 55 sweeping works spanning hyperrealism, illustration, mixed-media, and photography, depicting greatness not as an end goal but as a journey toward personal fulfillment. Whether in an empty martini glass left to glisten in the morning sun, or in the shadows of a faceless street vendor, this collection asks you to probe what you see: what stories are being sold, and what truths are brewing beneath the surface?

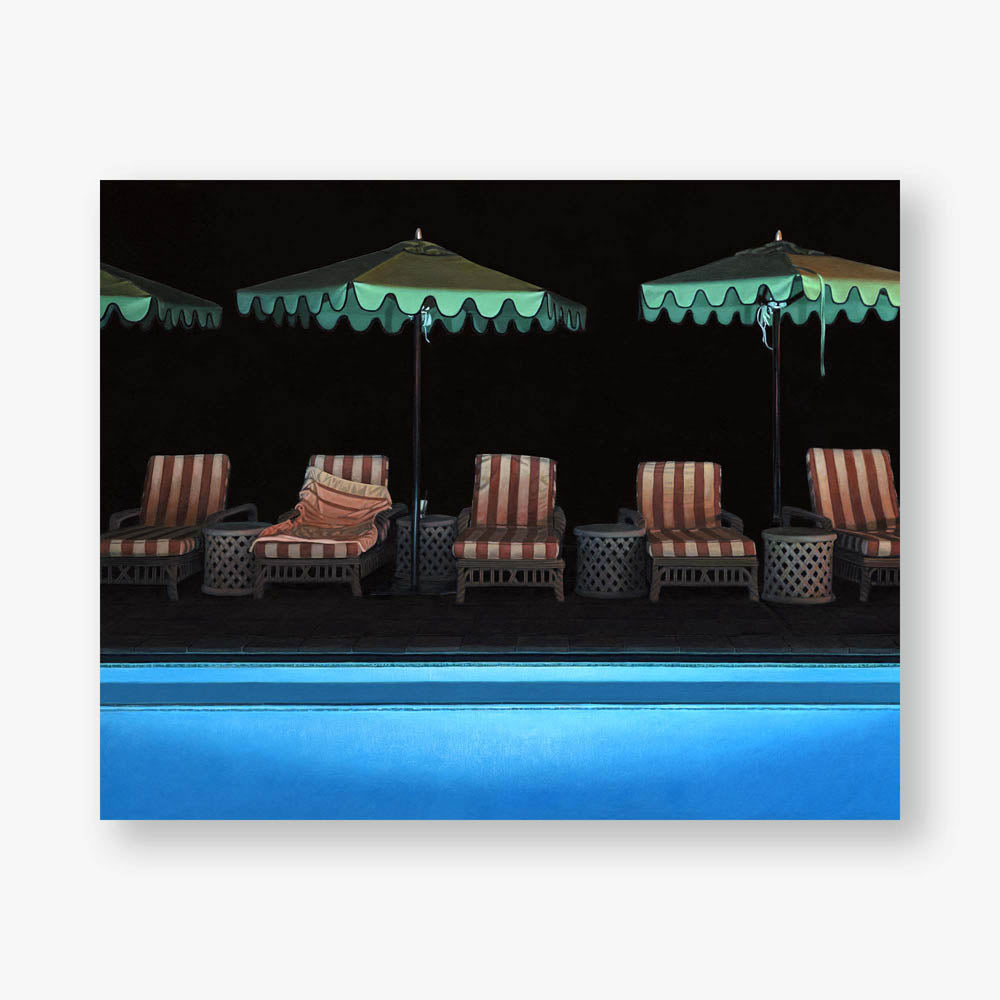

Leah Giberson and Alicia Hobbs, American painters working on opposite coasts, play on the novel’s growing unease that culminates in violence at its tragic end. In Leah’s Still in Darkness, painted in painstaking hyperrealism, five pool chairs sit empty beneath slime green umbrellas, the black night contrasted against their cool glow. Leah transports us to a moment in the wee hours of the morning when the last reveler has stumbled home. The noise subsides and the long-awaited drunken hoopla is exposed for what it was: a dark abyss of emptiness. Likewise, in Alicia’s Tea Set for Confessions, Gatsby’s boast-worthy silk shirts are reduced to a quilted tablecloth. A tipped tea cup is perched above it, rattling Gatsby’s nerves as he hosts Daisy for tea—will the confessions bubble up inside him or spill as quickly as the teacup teetered under the weight of this tension-filled reunion?

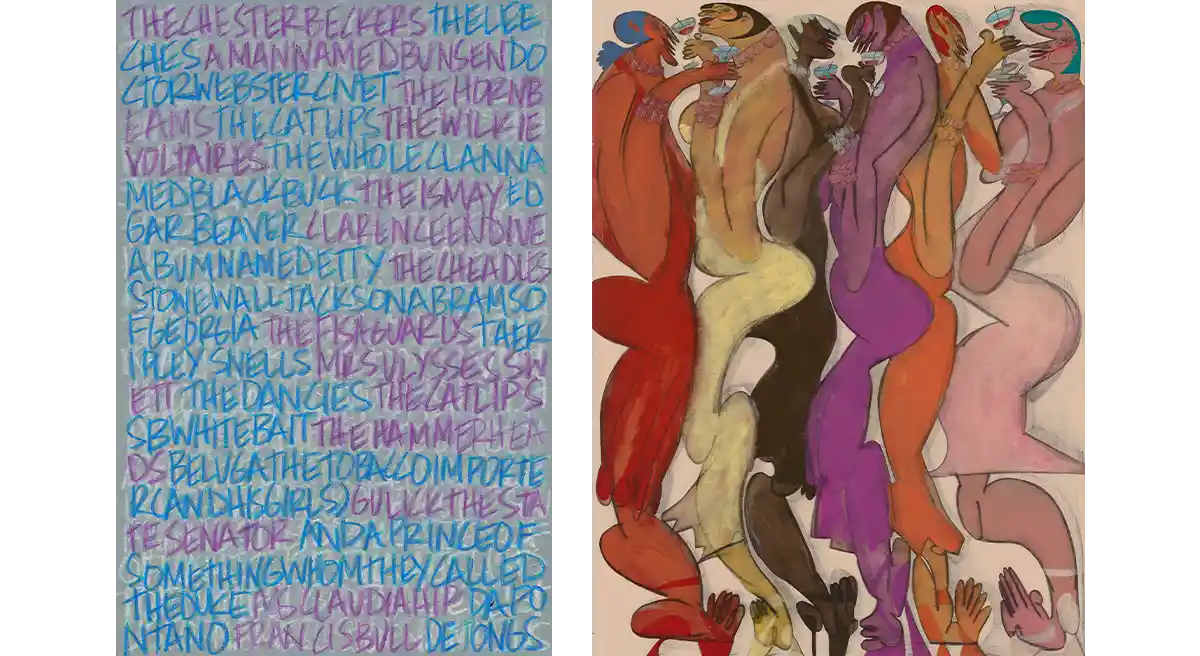

At Gatsby’s infamous parties, Tom, Daisy, Gatsby, Nick, and Jordan, America’s favorite cast of A-list characters, mingle with a hilarious, self-indulgent crowd of well-heeled party-goers from Long Island’s North Shore. Think WASPy men in tailored suits and well-shined shoes with their rouged ladies in tow. But who are they and where do they come from? Text artist Brian Graves explores this very question in The Guest List, riffing off Fitzgerald’s satirical list of pretentious names, not limited to “the Willie Voltaires,” “the O.R.P. Schraeders,” “the Stonewall Jackson Abrams,” and “Mrs. Ulysses Swett.” Also tuning into the absurdity of merrymaking, Kevin Sabo from Richmond, Virginia, depicts the blurriness of intoxication in Sweet Fever. Gender norms loosen and personal space becomes yesterday’s worry in this fantastic take on soirees for socialites.

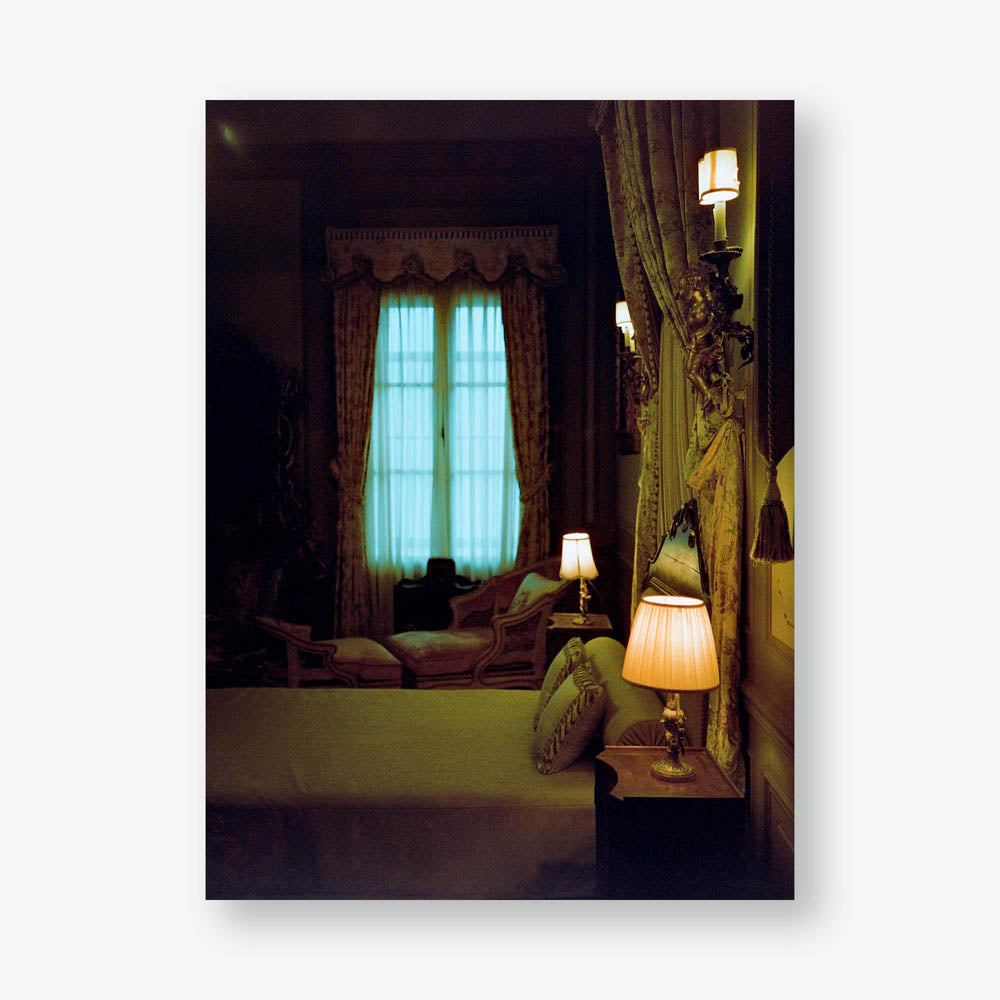

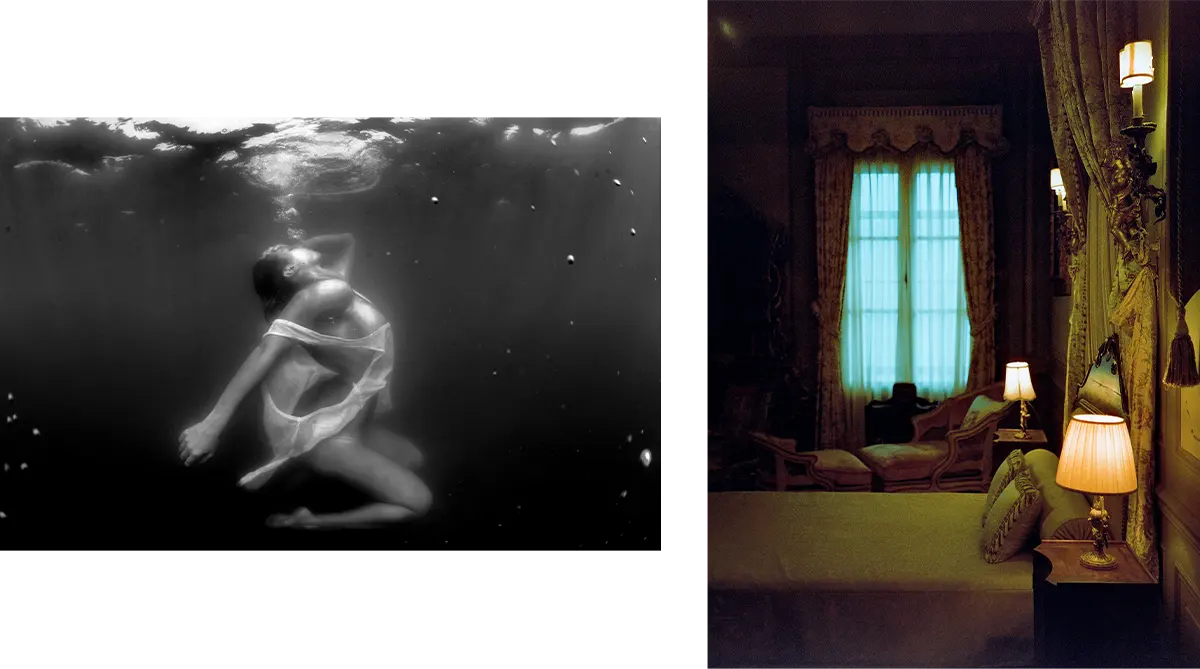

Brave enough to capture the longing that drives Fitzgerald’s two most evasive (and central) characters—the long lost lovers at the novel’s core—artists Matt Mele, James Katsipis, Atanda Quadri Adebayo, and Eric Haacht center Gatsby and Daisy’s elusiveness. In Divine Feminine, Matt smartly portrays Daisy’s bedroom—lit from a green glow shining through her drape-covered windows—as immaculate, empty, and ornate, a metaphor, perhaps, for an inner world that is as vacant as it is unattended. In Torn and Tattered, James takes a very different approach, depicting Daisy as what he calls a “mermaid of Montauk”—a sensuous surfer gal whose dramatic underwater pose nods to the performative, trope-like qualities of Daisy’s whiteness and inherited wealth.

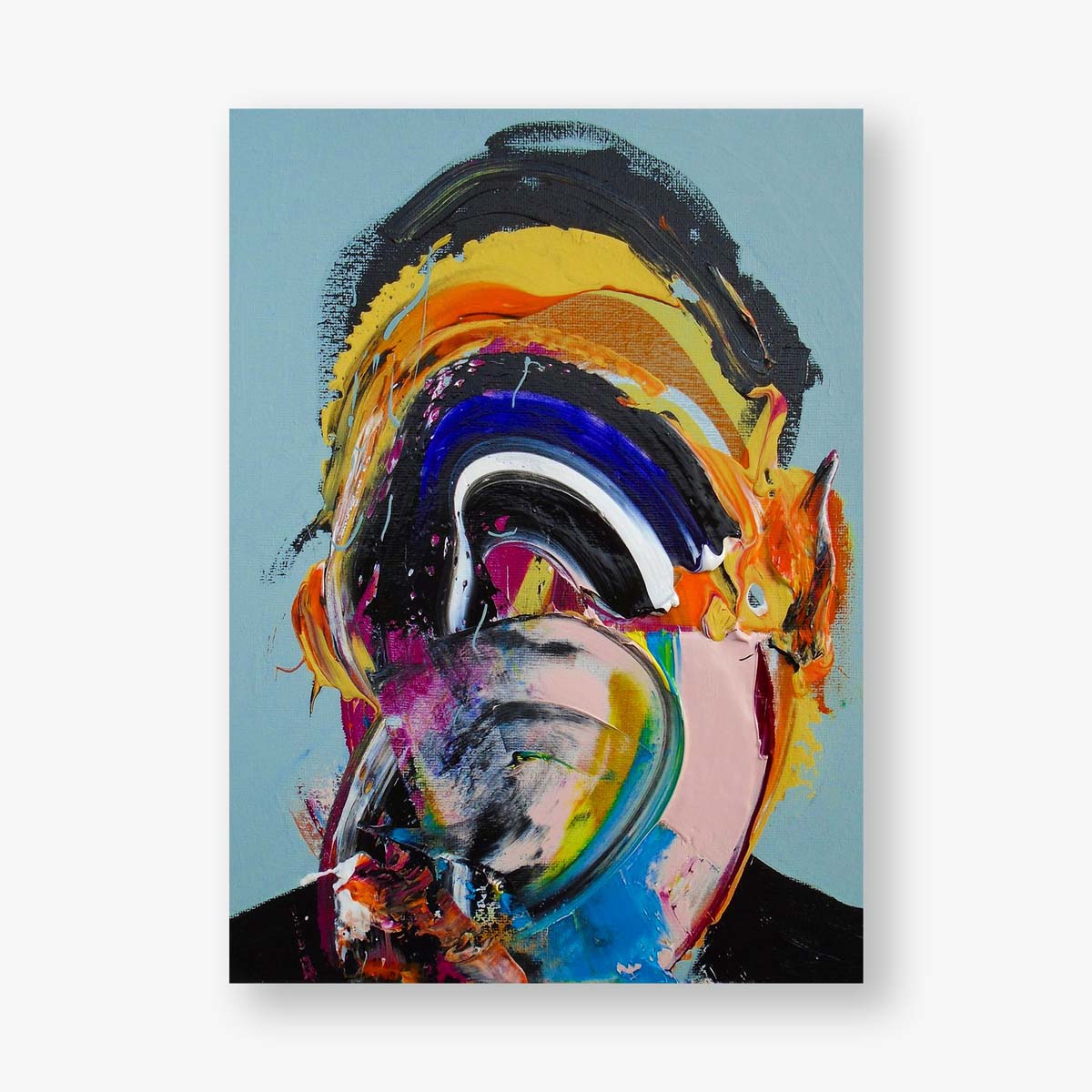

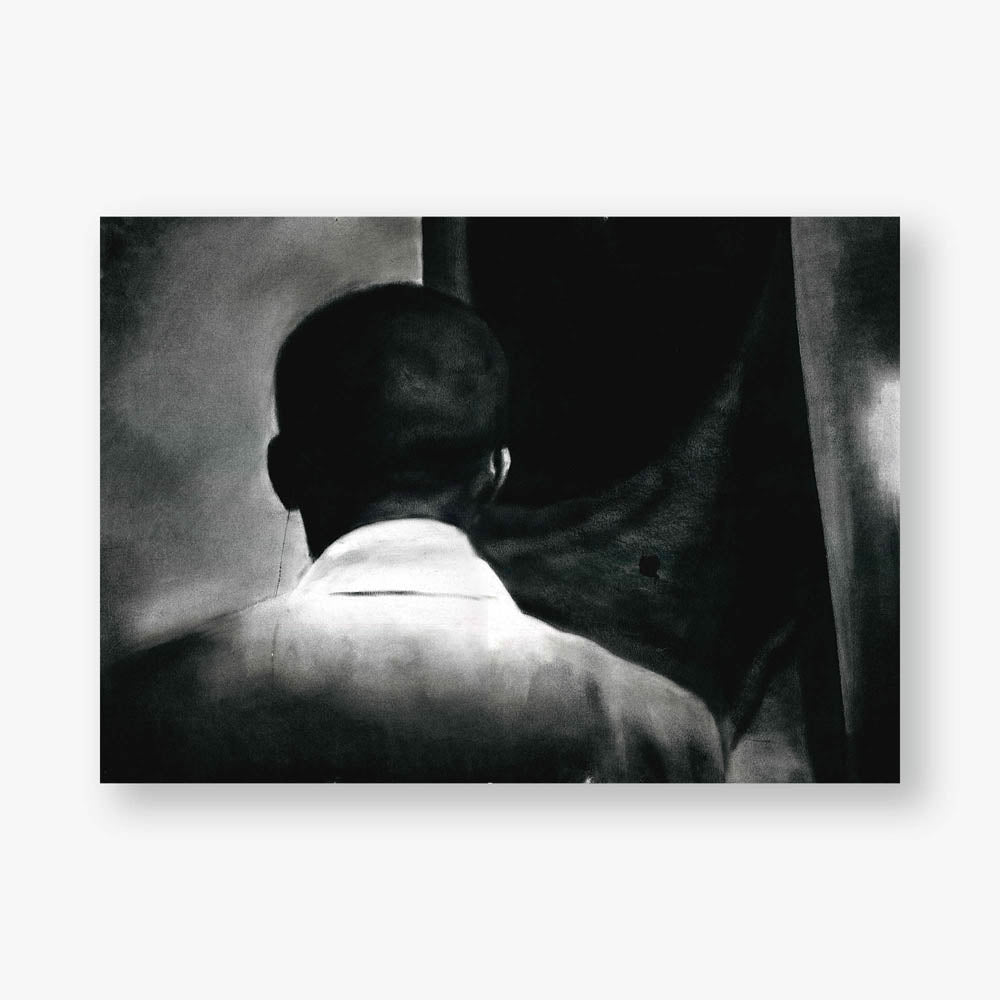

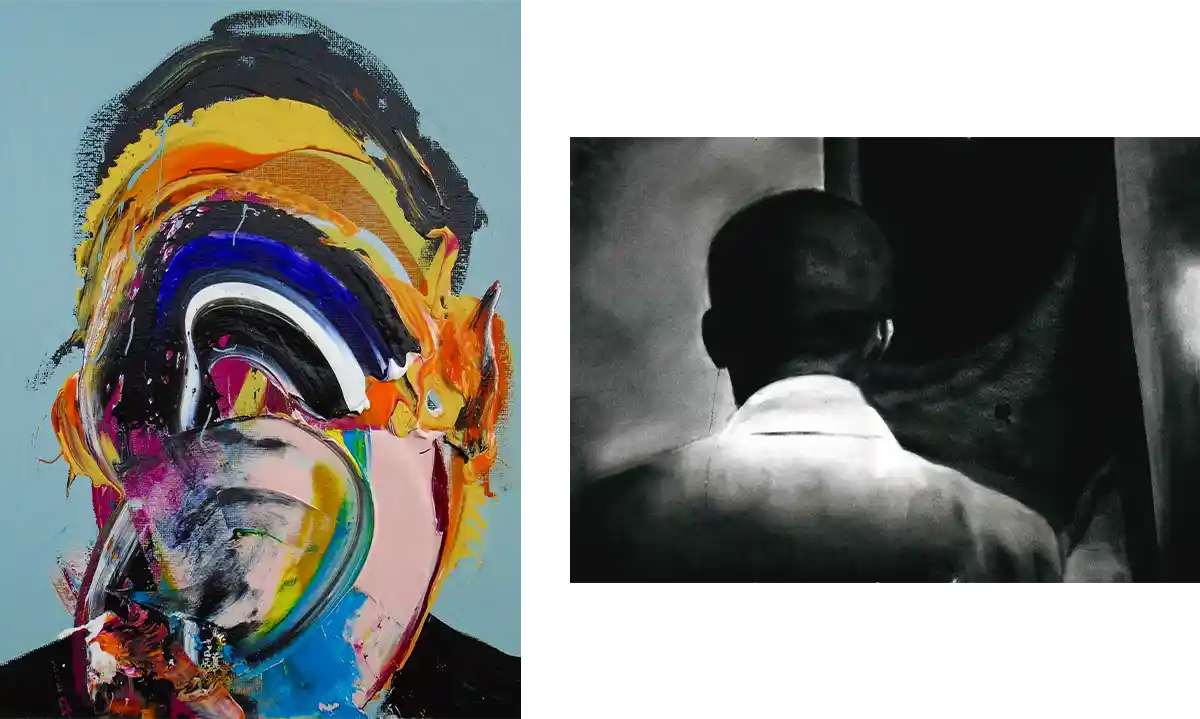

Gatsby’s character is notoriously impossible to pinpoint in words or visuals, and so Eric Haacht targets his essence instead, presenting Gatsby with a kaleidoscopic stroke of paint obscuring his face. In the end, Gatsby is who the reader decides he is—a figure shaped by society or a self-made man? A showman or truthseeker? Depends on your vantage point, and the way you see. Atanda likewise presents Gatsby faceless in Untitled (The Wall), standing, perhaps, in the wings of a theater stage or behind a cracked door. Atanda asks, “What happens when identity is defined by what is hidden rather than what is seen?”

“Gatsby believed in the green light,” Fitzgerald writes, “the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us.” Indeed, it was a dream that motivated him and consumed him, warping his reality like a fun house carnival mirror. Sheyda Mehrara and Blayne Pearce Planit tackle the bold and inconclusive question of what it means to dream as an American today; Sheyda likens the green light to a “fresh cut” wound over his hear, and Blayne, a light that is both brilliant and waning, just like the dream of Daisy—illusory but glowing. Green evokes both grass and emeralds, calm and envy, a paradox that both these artists explore as they work in intuitive abstraction to portray Fitzgerald’s poignant exploration of desire, longing, loss, and lust.

And finally, Lea Woo, Alexander “Gino” Gaggino, and Cass Waters bring their lived experiences to this quintessentially American novel with bold force, prompting us to reflect on the story through the eyes of secondary characters and fringe perspectives. After all, Fitzgerald inserts the downtrodden Valley of Ashes—and its “ash gray” men who disappear behind clouds of dust—into the story as a reminder of America’s diminishing morals, something these artists don’t take lightly.

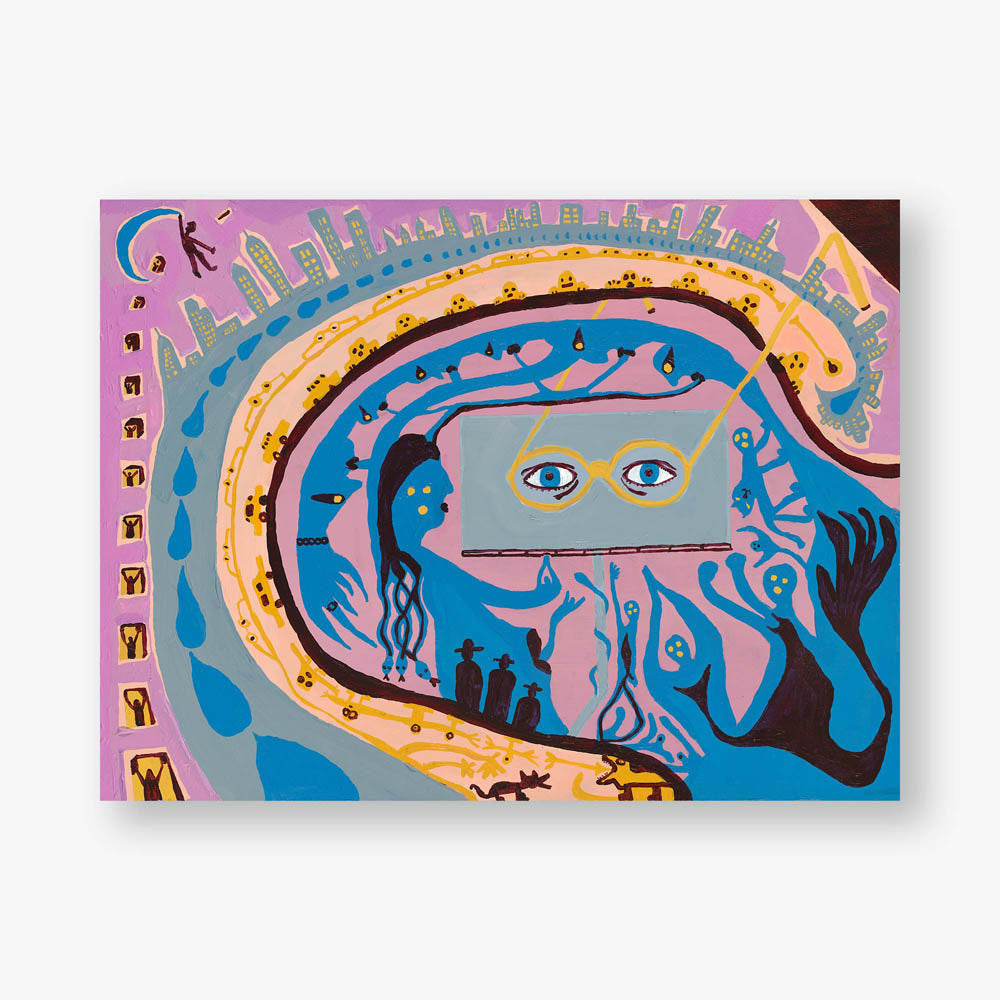

Through Art Deco-inspired digital illustration, the Shanghai-based artist Lea Woo presents Jordan as an empowered, fashion-forward New Woman. Of Asian descent, she golfs with conviction. Cass Waters of New York looks beyond the novel’s central cast and into the modern-day Valley of Ashes—the outer boroughs of New York City, where families live beneath bellowing train lines and pollution circulates. Queens showcases a faceless figure disappearing under the menacing overhead pass behind them, the painterly figuration loose and unfinished. And lastly, multimedia artist Alexander “Gino” Gaggino paints the scornful eyes of Doctor T.J. Eckleburg into Observer, an undulating, surrealist-inspired work that draws on the underground energy of the artist’s own background as a DJ and party host. Gino’s biomorphic forms vibrate with both ecstasy and unease.

To collect one of these works is to step into a century-long conversation about what it means to dream in America—from the rip-roaring Jazz Age to the uncertain present. “A Vivid Glimpse” is meant to unsettle and provoke, asking you to look both inward and outward: at where we’ve been, and where we still have to go as individuals and as a nation. As John Berger wrote, “the more imaginative the work, the more profoundly it allows us to share the artist’s experience of the visible.” That sentiment runs through Gatsby and through this layered reflection of America itself, a concept Maggie and I used to conclude our curatorial statement for the collection:“Only through interrogation do we deconstruct our own beliefs. This process of seeing and reseeing, of rewriting the narrative, is an American experience in itself. The intersection of multiple truths from perspectives far and wide is what creates the rich tapestry of American culture in all its discourse. Truth requires more than just a glimpse.”

To learn more about our art-centric approach to classic literature, read this interview in The Observer with our Creative Director Maggie Lemak.